- Home

- Lois Lowry

Taking Care of Terrific Page 5

Taking Care of Terrific Read online

Page 5

"What are you talking about, Seth?" I asked in a bored voice.

He lowered his voice to make it sound really subversive. "I've seen you, Enid. I was on my bike, heading over to Tremont Street on an errand for the station manager, and I saw you in the Public Garden, hanging out with that black guy. He's practically old enough to be your father."

I groaned. But I lowered my voice, too, in case my mother was still spying. I didn't want my parents to know about Hawk; it was just too complicated. "That's just a friend, Seth—"

He laughed his sinister, knowing laugh. "That's what they all start out thinking," he said.

"All who?"

"Young girls who come to Boston and meet these guys in the parks. Seems like a simple pickup at first. I saw this TV show about it. A documentary; we have it on tape down at the station. These older guys befriend them, maybe loan them a little money—"

I thought of Hawk, buying me and Tom Terrific each a green Popsicle. He hadn't said it was a loan.

Seth was going on and on. "Then before they know it, they're trapped. Hooked on heroin, probably. Owing hundreds of dollars. So they go to work for the guy. There they are, prostitutes, only fourteen years old. Three weeks before, they were innocent little cheerleaders, back in Ohio—"

"Knock it off, Seth."

"Eventually their bodies are found, in warehouses and culverts. Needle marks on their arms. Knife scars. One of them was disemboweled; they couldn't show it on the film, it was too gruesome. The detective who found her had tears rolling down his cheeks during the interview. 'She could have been my own little girl,' he said—"

"Seth," I said furiously. "You. Are. Such. A. CREEP."

His voice changed from the sinister whisper to an arrogant, know-it-all sort of voice. "You may think I'm a creep," he said. "But your parents won't think I'm a creep when I come over there wearing a clean shirt in order to warn them about what the future holds for their precious, brainy, artistically talented little girl."

Now I was really mad. "You wouldn't," I said.

"Wouldn't IP" He laughed. "Unless—"

"Unless what?" He was going to blackmail me in some way. I could hear it coming.

"Meet me at your corner in fifteen minutes," said Seth. "We'll walk over to Florian's and get a couple of those fruit drinks."

The Café Florian sells these great drinks in summer: fresh fruit all zapped in a blender.

"Those are expensive, Seth." I groaned. "If you're going to blackmail me, couldn't you start small, maybe with a Coke?"

"Don't sweat it," said Seth. "I'll pay. Fifteen minutes, at your corner." He hung up.

I went to my room and combed my hair and put on a sweater. Then I went back downstairs to tell my parents that I was going to meet a blackmailer in order to persuade him not to let them know that I was about to be part of the white-slave traffic, seduced by a strange man I'd met in the Public Garden, that I would probably be hooked on heroin quite soon, that they would likely never see me again.

"I'm meeting Seth," I said casually. "We're going over to the Café Florian for a little while."

"That's nice, dear," said my mother, looking up briefly from a medical journal.

"Be home by ten," said my father, adjusting the color on the TV.

Seth was waiting on the corner when I got there, his body kind of draped against a tree. He's skinny, all arms and legs, and he was wearing cut-off jeans and a tee shirt, which made his arms and legs more visible than they are during the school year. Our school has a dress code: jackets and ties for the guys; skirts or dresses for the girls. We all look like a bunch of corporation executives during school. Even our hair has to be neat. After the movie "10" came out, Trina Bentley came to school with her hair like Bo Derek's, in a million miniature braids decorated with beads, and she was sent home to undo it, even though it had cost forty-five dollars to have it done that way. Then there was a big flap because the three black girls in the Upper School argued that they should be able to wear their hair Bo Derek style since that was an authentic Afro-American style. Finally there was a compromise: braids yes, beads, no. By the time they reached the compromise, no one cared; school was about to end for the year, and the styles were changing anyway.

Seth had let his hair grow for summer, and it looked pretty good, curly and thick. He had gotten tan, and his skin had cleared up some since I'd seen him last.

Unfortunately, he still had his usual patronizing, sarcastic look on his face. Also, he has this knack of raising one eyebrow at a time. He raised the left one when he saw me coming.

"So," he said, "the big Enid Crowley. Lemme check your arms for needle tracks, kid." He was doing a bad Humphrey Bogart imitation.

"Bug off, Seth. I'm not mainlining yet."

He peeled himself off the tree and we crossed Marlborough Street side by side. Even though I knew none of my school friends were around, I checked automatically, glancing at the few people who were passing. I didn't want anyone I knew to see me with Seth Sandroff, Mr. Unpopularity.

We crossed Commonwealth, my favorite street in Boston even though it's the street where the Sandroffs live. Commonwealth Avenue has a wide center strip of grass and trees, with benches and flowerbeds. The sun was setting, and everything was bathed in a pastel light. A woman on a bench was jiggling a carriage, rocking a baby to sleep, and reading a magazine. Two toddlers played in the grass while their mothers talked. A jogger passed us, panting rhythmically. A gray-haired man with a pointed nose walked a gray-haired dog with a pointed nose. A Chinese couple was laughing, the girl hiding her mouth behind her cupped hands. Pink-gold sunlight glinted off the windows of the apartment buildings; a soft breeze blew; and I wished that I were wearing sandals and a full-skirted dress of some light, swirling fabric and that I were with almost anyone else in the world but Seth.

He demonstrated his remarkable ability to maintain the mood of a fragile, fairy-tale summer evening by saying abruptly, "The Nerd Sisters went to Fat Camp."

I translated that to mean that the twins, Arlene and Marlene, had been sent to one of those camps for overweight adolescents that advertise in the back of the New York Times magazine: "Lose Weight the Fun Way."

"You're really, really supportive, Seth," I said sarcastically.

"Well, at least they're not hanging out in the Public Garden, looking for trouble." We turned onto Newbury Street and headed for the Café Florian. Here there were many more people; a few of the stores were still open, and shoppers carried packages, hailed taxis, and greeted one another on the street. But the pace was slower, quieter, than the pace of the day. Now it was cocktail time. Dinner time. Theater time. Date time.

And blackmail time, I thought bitterly as I sat down with Seth at a small table on the sidewalk in front of the Florian. Next to us, a tall woman who looked like a model was eating a salad and reading a paperback. At a nearby table, two thin, well-groomed men were drinking wine; one was chuckling as the other told an anecdote in a low, gleeful voice.

The waiter brought our order of the two thick, slushy drinks, and Seth paid him with a crumpled five-dollar bill that he fished out of his pocket.

"Now," he said, turning to me, "tell me all, Enid, or I'll tell your parents."

"You're a creep, Seth. What I do isn't any of your business."

But he didn't answer. He just sat there, grinning arrogantly. It was really surprising how much better he looked in the summertime.

I told him a little about Hawk and about Tom Terrific. He interrupted me with a skeptical frown when I mentioned the little boy's name.

"No," I explained, "of course that's not his real name. His real name's Joshua. But what the heck, I told him he could change his name, just in the Garden. There's nothing wrong with that. I even change my own name when I'm there," I added defiantly. "I call myself Cynthia."

I expected him to hoot with laughter. But he just kept staring with an odd, quizzical look.

"Well, look," I said. "I really hate the name Enid. You probably wouldn't

understand that. Seth isn't such a bad name. But Enid—" I shrugged and leaned over my drink. Down at the bottom you can spoon up whipped cream and mashed peaches and strawberries. "Anyway," I said angrily, "it really isn't any of your business, Seth Sandroff."

"Sethsandroff, Sethsandroff, Sethsandroff," he said in a fake voice, kind of imitating mine. The woman reading at the next table glanced up from her book, puzzled, then looked back down and turned a page.

"You make me sound like a Russian general," Seth said.

"Oh," I said, realizing he was right. "I'm sorry. Well, if that bothers you, maybe you can understand what I mean, about having a place where you can call yourself whatever you want."

"Yeah. I guess."

"The thing is, Seth"—I was really getting into it now, since I'd never had a chance to talk to anyone about it before, except for a few attempts with Mrs. Kolodny, whose mind was off in outer space half the time—"nobody ever thinks about what other people want, you know? Like old Tom Terrific. His mother just announces what he's supposed to do. It never even occurs to her to ask him, or that maybe he'd like to get dirty sometimes, or eat junk food. And, well, here's another example, Seth: your sisters."

Seth made a face.

"Well, okay, I know you're not crazy about your sisters. But they probably wouldn't be half as repulsive as they are, Seth, if sometime way back your mother had realized that they didn't want to be cute little matching clones!"

"You like baseball?" Seth asked. "You want to go to a Red Sox game some Saturday?" That was his very subtle way of changing the subject.

"No. I hate baseball games."

"Well," said Seth sarcastically, "I appreciate your very gracious refusal of my invitation. It did wonders for my fragile ego."

I groaned. "Sorry," I said.

The waiter came over and asked if we wanted anything else, which meant would we please leave so that someone else could have the table and he'd get another tip. The waiter was more subtle than I was.

We walked back the way we'd come. It was dark now, and most of the people were gone from the grassy strip in the center of Commonwealth Avenue. A derelict had settled down on one of the benches, to drink wine out of a bottle in a paper bag and to sleep. It reminded me of the bag lady in the Garden. I wondered where she slept at night. I wondered what her dreams might be.

I told Seth about her as we turned onto Marlborough Street and toward my house.

"So if I can get Hawk to help, we're going to organize the bag ladies and picket the Popsicle man," I explained. "Make him pay some attention to what they want."

"You could get yourself in big trouble," Seth said, but I thought I could hear some admiration in his voice.

"No, I won't. It's legal to picket."

"Hey! If you tell me when you're going to do it, I could get a camera crew down there. It'd be a great human interest story! They're always looking for stuff like that down at the station," Seth said.

"I don't think we want publicity, Seth. We only want root beer Popsicles for the bag ladies."

He shrugged. "Suit yourself. Let me know if you change your mind."

We were in front of my steps when something occurred to me. I had explained to Seth about Hawk and about my relationship with him, but I still didn't know if he was planning to tell my parents the way he'd threatened to. He hadn't ever given me his blackmail proposition because we'd started talking about other things.

"So, Seth," I said casually, "are you still planning to get me in trouble with my folks? Or am I supposed to pay you off, or what? I might as well warn you that most of my money goes for art supplies."

He looked insulted. "For crying out loud, Enid, I just said that so you'd go over to the Florian with me. I didn't want to spend the evening watching TV again."

"That's weird, Seth. Why didn't you just ask me to go to the Florian with you? I would've said yes." That was a huge lie, of course, but all of a sudden I felt sorry for Seth. That I would have said no was bad enough. But that he knew I would have said no was worse.

My sudden feeling of being sorry made me say something else impulsively: "My mother said to ask you if you'd like to come over for dinner some night."

"No," said Seth abruptly, the way I had responded to his suggestion of a baseball game. "I hate dinner," he added sarcastically. Then he turned without saying good-by and jogged off down the street, his long arms and legs pale against the darkness until he turned the corner and was gone.

Chapter 10

"Mrs. Cameron—" I started to say, but she interrupted and corrected me.

"Ms. Cameron," she said pointedly. It sort of confirmed what I had guessed, that she was divorced. I remembered Tom Terrific saying wistfully, "People like to think about their daddies." There was nothing I could do for him on that score. But I thought maybe I could do something in another department.

"Ms. Cameron," I said, "Joshua would really like to ride on the Swan Boats. Do you think—"

"Oh, no, dear," she said. "No, I think not. The Swan Boats are terribly picturesque, of course. But the fact is that it's really only tourists who actually ride on them. And they're so crowded. You just never can tell, well, what germs..."

It figured. People who live on West Cedar Street tend to have a negative view of tourists. You never can tell what sort of germs they may be bringing from Illinois.

Fortunately, Tom hadn't been in the room when I asked her. He came thumping down the stairs a minute later, very cheerful, not aware that another of his little-boy hopes had just been zapped like a fuzzy caterpillar hit by a spray of Raid. He had a box of crayons in his hand.

"Oh, lovely, Joshua!" said his mother. "Are you going to draw pictures today?"

"Yes," said Tom Terrific solemnly. "Of trees."

"What a good idea! Cynthia," she said to me, "why don't you tell him the names of the different kinds of trees? They're all labeled, you know. It would be a Learning Experience. I'm sorry you didn't make better use of the Field Guide to the Birds."

She dabbed his face with a dampened paper towel—to polish it, I guess, since it was already super clean. Then she patted his hair into the shape that the barber at Trims for Tots had meant it to be. Finally she kissed him on the cheek, then dabbed with the towel at the place where the kiss had been.

We all said "Bye-bye."

"You do the words, right? And I'll do the Popsicles," said Tom Terrific when we were out on the sidewalk. "I have lots of different browns." He trotted along beside me, clutching the Crayolas; it was the Giant box, the one with a hundred crayons.

"Okay." I agreed. Fortunately I'd already finished that week's assignment for art class: a still life, in charcoal. I'd done it at home, in my room, of an eggplant, a pewter pitcher, and a pear. Afterward I'd eaten the pear and returned the pitcher to the dining room cupboard. But I'd forgotten about the eggplant, and now it was brown and squishy, still sitting on my desk.

The remaining pages of a six-dollar sketch pad were going to go for Popsicle posters. I planned to Scotch-tape the posters to sticks, after they were done, so our picket line could carry them.

Hawk and the bag lady were going to be in charge of recruiting the picket line. They didn't know that yet.

But when Tom Terrific and I reached our usual corner of the Public Garden, I discovered that our partners in crime were way ahead of us. I hadn't had a chance the day before to tell Hawk about the bag lady's willingness to join the ranks. But this morning the two of them were sitting there together on the bench, Hawk's saxophone still in its case at his feet. They were deep in conversation, her straggly gray head nodding up and down close to his big black pillow of hair as they talked.

"We're working out the details of this caper," Hawk announced when we arrived. "Can you guys do the signs?"

I grinned and nodded. So did Tom Terrific. "I have lots of browns," he said happily, holding out his Crayola box. "Not even peeled yet."

Both Hawk and the bag lady acknowledged his statement with solemn nods. It surprised

me. It surprised me that the two of them—a black man maybe thirty, maybe forty, years old and an ancient vagrant with her worldly goods jammed into a giant pocketbook—with their different backgrounds, different lives, both knew what Tom meant when he said "not even peeled yet." I knew, of course. But I'm fourteen. I should have outgrown it by now, but I haven't: the feeling that things are A-okay if your crayons still lie in orderly rows, pointed at the ends, arranged by colors, a little rainbow secret in a box, and none of the tips worn flat yet, none of their paper coverings peeled.

Parents don't ever understand that. They think that when your crayons are broken and peeled and stubby, you can just dump them into a coffee can and they'll still be the same crayons.

I wondered suddenly, for the first time, if Hawk or the bag lady had ever been parents. But it didn't seem the kind of question I could ask.

"You two Rembrandts get to work," said Hawk, getting to his feet, "and we two organizers will go out and give the marching orders to the troops. Tomorrow afternoon be okay? Four o'clock?"

"Sounds good to me," I told him, spreading my sketch pad open on the grass. I had a feeling that we were about to enter battle and that we should be whispering, "Synchronize your watches, men."

Tom Terrific hadn't been paying much attention to the conversation. He'd been removing his browns carefully from the box and lining them up in a row beside the sketch pad. But I noticed that now and then he lifted his eyes and glanced longingly over at the Swan Boats. One was gliding by quite near us, crowded with people: children holding balloons, a fat man aiming his camera (from which he'd forgotten to remove the lens cap; in two weeks he'd be wondering why his film had come back blank) at the ducks and water birds swimming beside the boat, mothers jiggling babies on their laps, teenage couples holding hands, and an elderly woman sitting primly, wearing an orchid corsage pinned to her blue silk dress.

I saw that for a moment the bag lady, too, looked wistfully at the Swan Boat. Then she and Hawk walked away, her shuffling steps speeded up a bit for his sake; his long, loping steps slowed a little for hers.

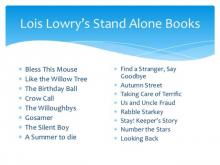

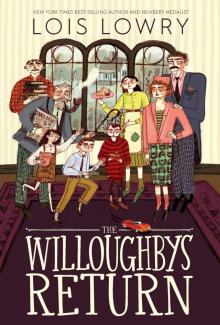

The Willoughbys

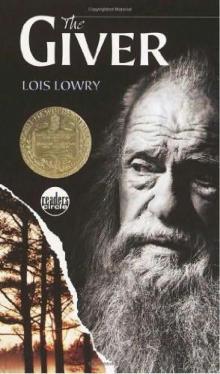

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

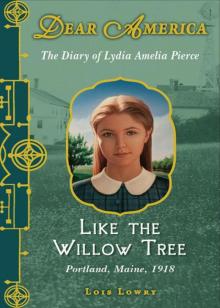

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

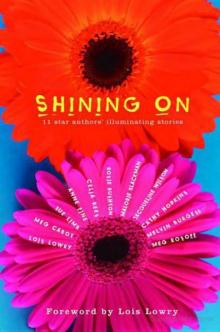

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver