- Home

- Lois Lowry

All About Sam

All About Sam Read online

All About Sam

Lois Lowry

* * *

Illustrated by Diane deGroat

Houghton Mifflin Company

Boston

* * *

Text copyright © 1988 by Lois Lowry

Illustrations copyright © 1988 by Houghton Mifflin Company

All rights reserved. For information about permission

to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue

South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lowry, Lois.

All about Sam / Lois Lowry : illustrated by Diane de Groat,

p. cm.

Summary: The adventures of Sam, Anastasia Krupnik's younger

brother, from his first day as a newborn through his mischievous

times as a toddler

ISBN 0-395-48662-9

[1. Family life—Fiction.) I. deGroat, Diane, ill. II. Title.

PZ7.L9673A1 1988 88-13231

[Fic]—dcl9 CIP

AC

Printed in the United States of America

QUM 20 19 18 17 16 15 14

* * *

For Jamie,

who is very much like Sam

* * *

1

It had certainly been an exciting morning for him, but a confusing one, too. There were bright lights, which he didn't like, and he was cold, and someone was messing around with his belly button, which hurt.

And he didn't know who he was yet.

"A fine healthy boy," he heard someone say. But that told him only what he was, not who.

He squinted and wiggled and stuck his tongue out, and they all laughed. He liked the sound of the laughter, so he did it again, and they all laughed some more.

Then they put some clothes on him, which made him nice and warm, though the clothes felt odd because he had never worn clothes before.

They passed him around from one person to another, which was a little scary because he was afraid they might drop him.

"Don't drop me," he wanted to say. But it came out sounding like "Waaaahhhh." Someone said "Shhhh" in a soft voice and patted his back gently.

"Who am I?" he wanted to ask, but that sounded like "Waaaahhhh" again, and she simply patted his back once more.

Finally they put him down in a little bed and dimmed the lights.

He opened his eyes wide now that the lights weren't so bright, but he couldn't see much: just the sides of the little bed, and high above him the blurred faces of people.

It was all too confusing and exhausting. He sighed, closed his eyes, and went to sleep.

When he woke again, he was in a different place. He was still in the little bed, but the bed had been moved; he knew because the walls were green instead of white. Now there were fewer people—fewer faces looking down at him. He could see these people a little better because his eyes weren't quite so new, so he blinked to focus more clearly and stared up at them.

There was a woman, and he could tell that he liked her a lot. She had happy eyes and a nice smile, and when she bent closer and touched his cheek with her finger, it was a gentle touch filled with love. He wiggled with happiness.

Then the woman's face went away, and a man leaned down. The man seemed to have his head on upside down; there was hair on the chin, but none on the head. Maybe that was the way men were supposed to look. The man had a nice smile, too.

Finally, a girl leaned over the bed. She had hair the same color as the man's chin hair, and she wore glass over her eyes, which were interesting to look at. But she wasn't smiling. She had a suspicious look.

The girl stared at him for a long time. He stared back. Finally she reached in and touched his hand. He had his hand curled up because he hadn't yet figured out anything interesting to do with it. But when the girl touched his hand, he grabbed her finger, which was just the perfect size for grabbing. He held on tight.

"Hey," the girl said, "I really like him!"

Of course you do, silly, he thought. He tried to say that, but only managed to spit and make a sound like "Phhhwww."

The man and the woman had happy smiles, which they aimed at the girl.

"Does he wet his diapers a whole lot?" the girl asked the man and the woman.

Yes, he thought, I do. As a matter of fact, I am wetting them right now, right at this very moment.

"He's only five hours old," the woman said. "So I haven't had time to conduct an exhaustive study. But in all honesty, Anastasia, I have to tell you that I think he will probably wet his diapers a whole lot."

You're right, he thought. I plan to. Because it feels good.

He yawned. They were talking to each other, but he didn't understand what they were saying, and he was a little bored. He was sleepy, too.

Then he heard the man say, "Have you picked out his name?"

And he heard the girl say, "Of course I've picked out his name."

So he tried hard to stay awake, even though he was sleepy, because he knew this was important. He blinked and yawned and wiggled and wet his diapers a little more, and waited. He waited while they murmured things to each other, which he couldn't hear. Then, one by one, they leaned over his bed again.

The girl with the pieces of glass over her eyes peered in at him, and now she was smiling. "Hi, Sam," she said.

The woman with the gentle voice looked down, and she said, "Hi, Sam."

The man with his head on upside down leaned close. In his deep, pleasant voice, he said, "Hi, Sam."

Oh, he thought happily. Now I understand. This is my family. My sister, my mother, my father.

And I am Sam, he thought and liked the sound of it.

Sam.

Sam.

SAM.

Sam was glad when they told him they were taking him home, because the word home sounded kind of nice, especially the way they said it to him in warm, happy voices.

But he hated the hat.

He didn't mind the dry diapers—by now, after three days, he was quite accustomed to getting dry diapers. He liked the chance to kick his legs in the air while they changed him, and he loved the soft feeling of the powder they sprinkled on his bottom.

He didn't mind the nightgown, though he hated it when they remembered to fold the mitten part over his hands. It was much better when they left the mitten turned back, because on each hand he had fingers and a thumb that he liked to suck when he was bored, or if they didn't feed him quite quickly enough when he was hungry.

But today, for the first time, they put a sweater on top of the nightgown, and the sweater was scratchy. I don't like this, he thought.

Then they put on the hat. And he hated the hat. It hurt under his chin where they tied it, and one of his ears was folded right in half inside the hat. He found the edge of the hat with one hand and tried to pull it off. They laughed and covered his hand with that terrible mitten.

I HATE THIS HAT, he yelled. But it sounded like "Waaahhhh," and they all said "Shhhhhh" and patted his back.

I HATE THIS HAT, he yelled again, and they jiggled him up and down and kissed his cheek.

"We're going home," they said.

NOT WITH THIS HAT ON, Sam yelled, but they didn't pay any attention to him, none at all. They wrapped a thick blanket around him, carried him through some doorways, down some halls, through some more doorways, and down some more halls.

It was about a hundred and fifty-three miles that they carried him, and for the entire distance he yelled, TAKE THIS HATEFUL HAT OFF ME!

But they didn't.

Then, suddenly, they went through one more doorway, and they were outside. It was cold and it was windy, and Sam had never felt anything like that before. He

closed his eyes tight and snuggled down into the blanket as far as he could. The man held him very close, and he could feel the man's jacket against his cheek. Only his nose and his closed eyes were sticking out of the blanket, and he could feel the cold wind on those parts of him. But he was warm everyplace else—even his head.

Okay, he thought; you guys know best. I guess I need this hat.

He liked the car. Its sound was interesting, and he especially liked the feel of it as it moved. He thought he might even fall asleep. But he stayed awake because the girl, his sister, Anastasia, was holding him now, and she didn't hold him as firmly as his father did. She wasn't used to him yet. He was afraid she might drop him.

Hold me tighter, he said. A little firmer arm under the head and neck, please. But it sounded like spitting noises, and she smiled down at him and giggled.

"Look, Sam," she said. "Look out the window. There's a big oak tree. It doesn't have any leaves yet, but it will, soon."

He tried to look, but the oak tree was too far away and the car was moving too fast.

"Now look, Sam," Anastasia said. "That's a maple tree. We're at the corner of our street."

She pointed, and he cringed. Please put that arm back under my bottom, he thought. And she did.

His sister moved him back and forth in her arms gently, and she sang to him. "Rock-a-bye, baby," she sang, "in the treetop..."

Oak tree, he thought. Maple tree. Treetop. Trees must be something important.

When they got home, he knew he was right. The man—his father—carried him into the house while his sister and mother walked beside him.

"Sam," his sister was saying in an eager, excited voice, "we just have a small apartment. And there wasn't an extra bedroom for you. So we fixed one up in the pantry. We painted the walls blue, and we put your little crib in there, and we took the dishes out of the cupboards and put your clothes in there, and Mom made curtains with unicorns on them just for you. I bet you're the only baby in Cambridge who gets to sleep in a pantry!"

Pan tree, thought Sam. Rock-a-bye, baby, in the pan tree. Okay. Whatever it means, I'm all for it, because she said "sleep." And I am very, very sleepy.

They laid him down in the crib, and the woman changed his diapers. She used the same soft powder that he loved. Then she took off his sweater and, finally —about time —she took off his hat.

He took a quick look around the pan tree, wiggled down beneath the blanket they put over him, yawned, found a finger to suck on, and closed his eyes.

2

At first he slept a lot. He couldn't think of anything else to do. The pan tree was pleasant enough, but it was kind of boring. Sometimes they took him out of his bed there and carried him around. That was always fun, because he got to look at different stuff, and his eyes were starting to work pretty well now.

He especially liked the rocking chair in the living room. His mom took him there to feed him, and sometimes he got so interested in listening to the squeak of the chair and looking at the pictures on the walls that he forgot to eat. Later, in his crib in the pan tree, he would think: I forgot to eat. Now I'm hungry.

So he would yell, I FORGOT TO EAT, AND NOW I'M HUNGRY. It sounded like "Waaaahhhhh," and he had improved his voice so that it was quite loud now.

When he yelled that, his mom would come. She would stand there looking down at him, and she would say, "Are you hungry again?" in an amazed voice.

Sam would say, IT'S BECAUSE I WAS LOOKING AT THE PICTURES ON THE WALLS, AND I FORGOT TO EAT! which sounded like a very long, very loud "Waaaaahhhhh." And his mom would sigh and take him back to the rocking chair and feed him again. She was a pretty good sport about it, except in the middle of the night, when occasionally she grumbled a little. And once, in the middle of the night, she fell sound asleep in the rocking chair. Her arms became limp and Sam had to say "WAAAAAAAHHHH" very loudly—more loudly than usual—because he was afraid she would drop him on the floor.

He wasn't often worried about that though, not the way he had been at first. No one ever dropped him. Not even when they gave him a bath and he was wet and slippery with soap. They held him good and tight. Even Anastasia had learned to hold him tight.

Sometimes Anastasia took him outside for a walk. He liked being out in his carriage because he got to look at trees and their moving leaves. The pan tree had no leaves, which was puzzling (he thought the pan tree was very weird compared to the outside trees), but finally they hung something over his crib. It had colorful things dangling from it, and if he bounced in the crib, the colorful things moved. He liked to look at that now and then—for about two minutes, no more. After that it was boring. When it got boring, he yelled, I AM BORED WITH LOOKING AT THIS THING OVER MY CRIB, which was a slightly different sort of "Waaaahhhhh."

The only bad thing about going outside was that dumb hat. They always put the hat on him when they took him outside, and they wouldn't take it off, not even when he yelled I HATE THIS HAT for a long time. So he concentrated on getting his hands to work better. Any day now he would be able to take that hat off; and when he mastered that, he would never ever wear that hat again.

There was a whole lot of stuff to learn, and it took a while. First he had learned to bounce himself in his crib, so that the hanging thing would move and be interesting for two minutes.

Next, there was the whole diaper-changing thing. After the soft-feeling powder got sprinkled on his bottom, which he liked so much that he always smiled—and they loved it when he smiled—then his mom would put the dry diaper on. Then—this was the best part—before she pulled his nightgown down, she would lean forward, put her face on his tummy, and go "Blur-ble blurble" with her mouth, which tickled so much that he would laugh out loud.

But when his dad or his sister changed his diaper, they didn't know that they were supposed to do the blurble blurble thing. So he had to teach them.

He taught them by yelling DO THE BLURBLE BLURBLE THING, which sounded like "Waaahhhh," after they changed him.

Then they would say, "Why does he always cry when we change him?" as if their feelings were hurt.

"I don't know," his mom would say in a puzzled voice.

IT'S BECAUSE THEY DON'T DO BLURBLE BLURBLE, he yelled, but they didn't understand him.

Finally —it seemed to take forever—one day, his mom said, "I bet I know!" And she explained to them about the blurble blurbling.

Sometimes they still forgot, but he reminded them each time, and they were learning.

Now and then they left him all alone, lying on a blanket on the living room floor. He wished they would hang around and make faces at him, but he understood that they had other stuff to do sometimes. And he liked the time on the blanket. He kicked his legs a lot and looked at the living room stuff. The curtains were nice, and the pictures on the walls were interesting, and sometimes they even left the TV on and he liked the voices of the TV people, though not as well as he liked his family's voices.

One day, when he was alone on the blanket on the living room floor, he leaned hard on his side and pushed with his arm. Arms were great pushers, he had discovered recently. He could use one arm to push away the spoon when his mom tried to make him eat oatmeal, which tasted disgusting.

"Sam, stop that!" his mom would say when he pushed the spoon away. So he would answer, OATMEAL IS DISGUSTING, which was a wonderful thing to say with his mouth full, because it sounded like "Phhllllt" and made oatmeal fly out of his mouth and onto his clothes. Then he could grab it with his hand and put it into his hair, which felt good. Even though he hated oatmeal, it was always fun to be fed oatmeal because he could smear it around and push the spoon and stuff, and sometimes it meant he even got a second bath, which he liked.

But on this particular day, lying on the floor, he wasn't thinking about oatmeal. He was thinking about his arm and about how it pushed.

He pushed harder and harder, leaning on his arm, and suddenly his whole body tipped over. He had started out on his tummy, and now he was on his back. H

e had also gotten a clunk on the head, but he didn't even care about that because it was so interesting, what pushing would do.

He began to wiggle and push again. It was harder, starting from his back, but he worked on it for quite a long time, until suddenly: clunk. He had done it again, and now he was on his tummy, but he was off the blanket.

Now he was on the living room rug, a place he had never been before.

He tasted the rug. Yuck. The rug tasted terrible, much worse than oatmeal; but that didn't matter because he wasn't hungry anyway. Sam was on a roll.

Lean. Push. Push. Up, up, up, and: clunk. He was over again. He was heading for the big green chair in the corner.

Now he was getting better at it. It didn't take so long each time. Clunk: tummy. Clunk: back. He wished that he didn't clunk his head each time. Tomorrow, maybe, he would concentrate on the head part.

There: he was at the chair. One more roll would do it. He pushed with his arm, raised his behind, leaned, and clunk. He was under the green chair, exactly where he wanted to be.

He lay there very quietly, looking up at the underside of the chair, where a metal thing poked out, and there were some dangling threads that were much more interesting than the thing that hung over his crib in the pan tree.

He could hear footsteps. He knew they were Anastasia's footsteps. Hers were noisy, and they had dangling shoelaces flapping, unlike his mom's softer steps or his dad's firm, big ones.

Sam waited. He smiled, waiting, under the green chair.

Then the footsteps stopped—they were quite close to him—and he heard Anastasia scream. "Mom! Sam's gone!"

He heard his mom's soft footsteps coming very fast. He waited quietly, smiling to himself.

"He was here ten minutes ago!" he heard Anastasia say. "He's been kidnapped! Someone climbed in the window and stole him!"

"That's impossible," he heard his mom say in a worried voice.

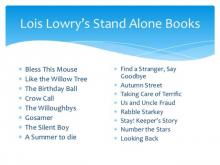

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

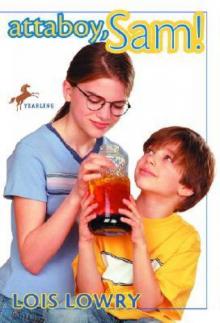

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver