- Home

- Lois Lowry

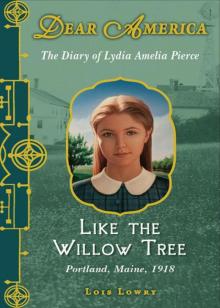

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Read online

DEAR AMERICA

The Diary of

Lydia Amelia Pierce

LIKE THE

WILLOW TREE

LOIS LOWRY

Contents

Title Page

Portland, Maine

Friday, October 4, 1918

Later

Saturday, October 5, 1918

Sunday, October 6, 1918

Monday, October 7, 1918

Tuesday, October 8, 1918

Wednesday, October 16, 1918

Friday, October 18, 1918

Saturday, October 19, 1918

Sunday, October 20, 1918

Monday, October 21, 1918

United Society of Shakers

Tuesday, October 22, 1918

Later

Sunday, October 27, 1918

Monday, October 28, 1918

Tuesday, October 29, 1918

Friday, November 1, 1918

Saturday, November 2, 1918

Sunday, November 3, 1918

Later

Sunday, November 10, 1918

Monday, November 11, 1918

Tuesday, November 12, 1918

Monday, December 2, 1918

Sunday, December 8, 1918

Monday, December 9, 1918

Wednesday, December 11, 1918

Thursday, December 12, 1918

Saturday, December 14, 1918

Sunday, December 15, 1918

Wednesday, December 18, 1918

Friday, December 20, 1918

Sunday, December 22, 1918

Wednesday, December 25, 1918

Friday, December 27, 1918

Wednesday, January 1, 1919

Friday, January 3, 1919

Saturday, January 4, 1919

Sunday, January 5, 1919

Monday, January 6, 1919

Thursday, January 9, 1919

Friday, January 10, 1919

Tuesday, January 14, 1919

Friday, January 17, 1919

Monday, January 20, 1919

Friday, January 24, 1919

Saturday, January 25, 1919

Sunday, February 2, 1919

Wednesday, February 12, 1919

Sunday, February 16, 1919

Thursday, February 20, 1919

Saturday, February 22, 1919

Thursday, February 27, 1919

Sunday, March 2, 1919

Tuesday, March 11, 1919

Thursday, March 13, 1919

Monday, March 17, 1919

Saturday, March 22, 1919

Tuesday, April 1, 1919

Tuesday, April 8, 1919

Saturday, April 12, 1919

Wednesday, April 16, 1919

Later. 2 p.m.

Later still. 7 p.m.

Sunday, April 20, 1919

Epilogue

Life in America in 1918

Historical Note

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Other books in the Dear America series

Copyright

Portland,

Maine

1918

Friday, October 4, 1918

I am desolate. Mother and Father had agreed that for my birthday today, they would take me (and my brother, Daniel, though I don’t think it was entirely fair that Daniel should be going, since it is not his birthday, just mine) to the moving pictures to see Tom Mix in Cupid’s Roundup at the Strand Theatre.

I have never been to the Strand Theatre and it has a Wurlitzer organ. And I have never seen Tom Mix, but he is King of the Cowboys and is deeply in love with the beautiful actress Victoria Forde.

I have always wished for my name to be Victoria instead of Lydia, which is as dull as dishwater. When my baby sister was born in July I hoped that we would name her Victoria, but Mother and Father thought it too fancy a name (it is a queen’s name, after all, they pointed out) and so our baby is named Lucy, almost as dull as my name, Lydia.

Mrs. O’Brien, next door, said she would watch Lucy for us tonight, so that we could go to the moving pictures. It would be a much more grown-up celebration than pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey at home with birthday cake. And grown-up suits me, for today I am eleven years old. I was born on October 4th, 1907, in this very house with its yellow clapboards and black shutters — both in need of paint, I’m afraid — and with its big porch and the forsythia bushes across the front of the yard. I was born upstairs in this house eleven years ago in Portland, Maine.

But now I am desolate. The Portland Board of Health has issued an order suddenly that no gatherings are to be held at theaters or motion picture houses or dance halls. None at all! And schools are to be closed as well. All because of a sickness that has arrived in Maine. It is called Spanish influenza. I do not know a single person who suffers from it and think it is all quite silly and it has completely ruined my birthday.

But for the occasion Mother and Father have given me this lovely journal to record my thoughts. I am only sorry that my thoughts are so distressed.

Later

Oh! I am adding this later! Mother has given me a special gift. She said she had been saving it for when I was older, perhaps thirteen, but she was sorry my birthday celebration has been canceled, and so she thought to give me this now. It is a ring, a beautiful gold ring, with an opal stone, and it was my grandmother’s. I never knew my grandmother, for all my grandparents died before I was born. But her hands must have been small. The ring fits me exactly, and I will wear it forever.

Saturday, October 5, 1918

Driving automobiles on Sunday has been outlawed for some time so as to conserve fuel for the war effort. But today it was announced that automobiles may be used tomorrow, so that people might have a day in the countryside and away from the crowded parts of the city where infection is spreading.

I would like a day in the country! But we do not have an automobile. Few people do. They are very costly, sometimes as much as $600. Father is only a store clerk, though he hopes to be manager of the store before too long. He works very hard and says that he will see to it that all of his children, even the girls, go to college. But we are not rich.

In the spring, before Lucy was born, we sometimes took the electric trolley up to the town of Gray. Uncle Henry would meet us there and drive us in his horse and wagon to the farm. Mother likes to see her brother, Uncle Henry, even though his wife, my aunt Sarah, is somewhat ill-tempered. Uncle Henry and Aunt Sarah have six children! There are three older boys who help a lot with the farm: John, Joseph, and Robert. Then twin girls named Margaret and Mabel, who are ten and very lively. And a small boy, little more than a baby, named Willie. No wonder Aunt Sarah is so ill-tempered, with all those children to care for! It is quite an adventure to go there.

They live in the countryside, just what Maine Fuel Administrator Hamlen says we need! But we do not own an automobile, and Mother says it is too hard to make the trip on the trolley with the baby so small. We must wait until Lucy is six months old, Mother says, and it will be easier. That is three more months! I am hoping, though, that we might go to Uncle Henry’s farm at Christmas.

And I am wishing that someone with an automobile would invite us for a ride tomorrow.

Beds have been put into the Italian church on Fore Street, so that people living in crowded houses where relatives are sick can go there to sleep and get away from the influenza.

I would certainly not want to sleep in a church with a lot of strangers. I like my own room with its flowered wallpaper and ruffled curtains. My doll-house sits on the floor beside the window, with the little people inside lying stiffly on their beds, and the tiny roast chicken on the kitchen table as it has been for years. My bed has a sp

read on it embroidered with sunflowers. My books are lined up on a shelf in the corner, and the lamp on the table beside my bed has a shepherdess on the shade, her painted hand forever above her forehead, as she forever looks across the pale green meadow for her sheep.

Lucy still sleeps in her little crib in my parents’ bedroom, beside their big bed, so that Mother can tend her when she wakes at night. When she is older she will share my room. I hope she never becomes the kind of child who grabs and breaks things! I will teach her to be careful.

At night, when everything is quiet, I can hear the tall clock ticking at the foot of the stairs. Father winds it each evening, checking the time against his pocket watch, sometimes moving one of the metal hands a tiny bit. Each hour it chimes, and from my bed I always hear the nine chimes and tell myself that I will stay awake to hear ten. But I never have.

Sunday, October 6, 1918

Even our church on Woodford Street has closed now, and so we could not go to Sunday School today. It is a little frightening and odd, big solid places like churches closing. The Catholic churches are holding their services out of doors. But our church has simply closed and so we held our own little service at home, and said the Lord’s Prayer at breakfast. Then Father read a psalm. Daniel was disrespectful and had to be punished. Mother told me later that fourteen is a very difficult age for a boy and she wishes Father would not be quite so harsh.

I wanted to walk to Emily Ann Walsh’s house on Rackleff Street and play there this afternoon. Emily Ann and I have been reading The Secret Garden together and acting it out. We take turns being Mary. It is especially fun in the beginning, when she is so sulky and tries to order the servants about! Now we have just reached the part where she finds the garden. We were planning to act that part in the Walshes’ backyard, where they have some thick lilacs, but Mother telephoned and found that Mrs. Walsh has taken ill. Mother thinks it is not the influenza but just a fall cold. Still, they should not have company because even a cold is contagious and she does not want me to catch it and give it to Lucy, who is still so small.

The newspaper says that fresh air is the best way to combat the flu. So I think that playing in Emily Ann’s backyard would have been a very healthy thing to do. I did not say that to Mother because it would have been arguing, and she has already had to talk to Daniel this morning about his disrespectful attitude.

Because we couldn’t go anyplace, I actually did some schoolwork this afternoon. Daniel has been helping me with South America. He is fond of maps and knows a great deal about the world. But I can never keep the South American countries straight in my mind (Chile is easy because it is so long and thin. And Brazil, so large! But the rest! Well, each one seems the same as the others!) and my teacher said I must work on learning them before the next test.

Daniel actually drew me a map with just the outlines of the countries. Then I had to fill in the names. I mixed up Uruguay and Paraguay once again! He devised a trick to help me remember: I think of the word up lying on its side, and if you look, you will see the P — Paraguay — up above the U. It seems to work. Daniel is very clever. I still have trouble with Bolivia, though.

He said he would quiz me again tomorrow, so I must study my map. In return I told him I will help him with his French. Not that I know French! But I will read the list of vocabulary words to him and check to be sure he spells them correctly. He finds French very tedious.

Mother is worrying about tomorrow because Marie, the laundress, has sent word that she cannot come. Marie lives near Fore Street, in the Italian section of Portland, and there is much sickness there. But what is Mother to do, with Lucy’s diapers, and the sheets, as well, to be washed? I suppose I will have to help.

I wish there would be school tomorrow. Then Daniel and I would not be confined in this house together, where — except when we are doing our schoolwork — he is determined to thwart and torture me in every way. He hid the book I was reading, Hans Brinker, just when I was at a very exciting part. Then he made me guess where it was by asking twenty yes-or-no questions: “Is it in the living room?” “No.” “Is it in the kitchen?” “No.” “Is it in the dining room?” “Yes.” Well, that narrowed it down, but the dining room has a large buffet, with drawers — each drawer a separate question — and also a closet, and just when I was running out of ideas, because all my questions got “no” answers, I thought to ask, “Is it behind a curtain?” which was a “Yes!” But there are long, thick curtains at every window in the dining room, and he said I must ask them one by one — but I only had three questions left by then! I made a lucky guess and found my book, but he had lost my bookmark and I had a hard time finding my place.

Mother sighed and said, “Daniel, don’t torment your sister so!” but he paid no attention. And in truth I saw Mother laughing a bit as I searched and searched for my book. So I am not entirely sure she was on my side.

(I plan to hide Daniel’s shoes when I have an opportunity. One will go into the umbrella stand just inside the front door. The other, I think, into the box where the milkman collects our empty bottles and leaves full ones. Daniel will never find them! Maybe I will charge him a penny for each, when I reveal where they are.)

As for Father, he ignored our fuss, as he always does, and went into the living room and read the newspaper. These days more news is about the influenza than about the war. He says they are making too much of it. He intends to go to work tomorrow and every day to follow, and he expects his fellow employees at the store to do the same. He thinks Mayor Clarke is a fool to close down a whole city.

Monday, October 7, 1918

So soon after I had made a vow never to remove my grandmother’s ring, I removed it in order to help Mother this morning with the laundry. I placed it carefully on the kitchen windowsill, where it sparkled in the light. But, oh, after we began boiling all the water for washing Lucy’s diapers and bed things, the windows became so steamed that we could not even see outdoors!

Fortunately the weather is fine, with sunshine, and we were able to hang the wet laundry out on the line, where it dried quickly in the breeze. I put myself in charge of that: hanging everything in neat rows, then bringing it in as it dried, and folding, folding, folding.

Daniel agreed, though in an ill temper, to lift the heavy tubs of water to empty them. Mother cannot do it alone. Nor can Marie, though she is very strong. Mother always helps her with the lifting.

Lucy was very agreeable this morning. We put her in her carriage on the back porch, for fresh air, and she kicked her legs under the blanket, and smiled. She was watching the breeze move the tree leaves, I think (some leaves are falling now, and they blow around). I could see her blue eyes moving back and forth, following. Then after a bit she fell asleep.

Father walked home from the store at lunchtime, as he always does, and praised us for doing Marie’s work so well. Then he noticed that we had not found time to prepare a meal! But he was good-natured, and we stopped our labors for a bit and sliced yesterday’s roast and buttered some bread. Daniel came in hungry, too. He had gone up the street to the Farlows’ house on Seeley Avenue and had been helping Martin Farlow repair a bicycle. Martin was supposed to be back at college by now, but Colby has postponed its opening because of the flu. Even that far away, in Waterville, people are ill!

Mother took a moment at lunchtime to telephone the Walshes’ house and found that Emily Ann’s mother is feeling a little better. But their next-door neighbor, Mrs. Flynn, newly married and expecting, is very, very ill, and the doctor has not yet found time to come. All the doctors are busy and the hospitals are filling up. Mrs. Flynn’s husband stayed home from his office and is trying to take care of her, but there is really not much to be done, Mrs. Walsh says, just to wipe her face with cool cloths and to urge her to have some broth. Her fever is very high and from time to time her nose bleeds. She does not recognize her husband, which pains him terribly.

Father says a few customers are still coming to the store, but the city streets are quite d

eserted, and many of those who are out and about are wearing gauze masks. I do not like to picture that in my mind: people with masks. It scares me. Mother said perhaps he should not return to work, but he was shocked at the idea. “What if everyone left their jobs?” he asked. “The city would cease to be!”

In truth I think he did not want to stay at home while all the laundry was being done, with the windows so steamed and the harsh smell of soap everywhere.

“Where’s the baby?” Father asked, and when Mother told him, he went to the back porch and kissed Lucy, who was still sleeping soundly with her tiny fingers curled into her hands. Then he took an apple from the bowl on the kitchen table, folded the newspaper, and walked off again, down to Stevens Avenue and around the corner.

When the laundry was finally finished, I put my ring back on and secretly hoped that Marie would be back soon, school would reopen, and I would not have to do laundry again, maybe ever in my life.

Tuesday, October 8, 1918

Young Mrs. Flynn died during the night. We heard this from Emily Ann’s mother, who was weeping when she called. She said Mrs. Flynn just got worse and worse, and didn’t recognize anyone, and toward the end could not breathe, and there was nothing they could do. Now her poor husband is very ill and there is no one to tend him. No doctors will come.

Volunteers, most of them women, are moving about the city by automobile, carrying soup and bread into homes where people are afflicted. But there is not much else they can do.

Father came home early and does not want supper. He feels very, very tired.

Wednesday, October 16, 1918

I have not written for eight days.

What could I write?

Father is dead.

Mother is dead.

My baby sister, Lucy, is dead.

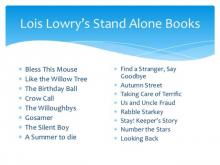

The Willoughbys

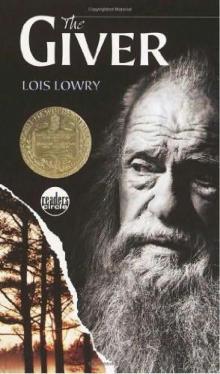

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver