- Home

- Lois Lowry

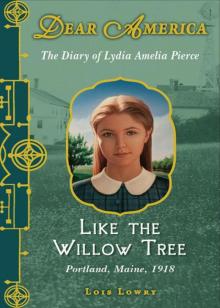

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Page 10

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Read online

Page 10

It was Eldress Lizzie who arranged for the community to have a telephone, and also — imagine this! — she was the one who bought the automobile, the Selden, ten years ago!

She did not complain about the pain in her ears, and she seemed to enjoy our conversation. But Sister Elizabeth whispered to me that I should be as quiet as possible because Eldress Lizzie was suffering. She will be taken to the doctor in Portland as soon as possible.

Walking back to the girls’ shop to tidy myself before supper, I stopped by the sheltered place where there is no snow and we can still find stones. It was cold and getting dark, but I leaned down and looked carefully and found a white one. Then, back in my room, I added Eldress Lizzie to my stone family. Her hair, beneath her Shaker cap, is white.

Saturday, February 22, 1919

Some of the sisters took newly made candy to the Mansion House to sell. They have been working on the candy for the past several days. Rebecca is working on the candy-making now, and I suppose when I open my mind to Sister Jennie next, I will have to confess to jealousy. I so want to work on the candy! But instead I am making applesauce and weaving poplar cloth, and washing pots and pans. Next I will be helping to package herbs. Do they not see that I would be very, very good at candy-making?

Thursday, February 27, 1919

The Shakers don’t celebrate their “real” birthdays, but instead what they call their “came among believers” day — the day that they entered the Shaker community. For me and my brother that would be October 22nd, the day we arrived at Sabbathday Lake.

But today — February 27th — is Daniel’s real fifteenth birthday.

He was three when I was born. Mother said that he could not pronounce my name, and he called me Lyddie. He mixed it up with the word little, and he referred to me as “the lyddie baby” and made everyone laugh.

His own name is Daniel Walter Pierce, named for his father and grandfather. Never once was he called Dan or Danny.

He taught me to throw a ball and to say the Pledge of Allegiance. We say it now each day in the Shaker school, and when I begin the words “I pledge allegiance to my flag …” I always remember Daniel showing me how to hold my hand over my heart.

He is no more than eight miles away from me now, but the distance seems a great one and impossible to bridge. I hope he thinks of me, of his Lyddie, and I pray that I will see him again in this life.

Sunday, March 2, 1919

With a new tongue I now will speak

And keep the valley lowly

I’ll watch my thoughts and words this week

And have them pure and holy

Sister Helen moved her hands in a particular way with this song, and the other sisters and the brethren joined in. It is called “motioning” and is not at all the same as the whirling and dancing and marching that Shakers once did. We girls watched and tried to do the same motions with our hands.

If we were doing this as a game, we would laugh at our own mistakes. But we do not laugh during the Sabbath meeting. Everything is quite solemn.

It is March. I have been here for four months. And still they have not set me to candy-making. It is hard to keep my thoughts pure and holy when I think about that.

Tuesday, March 11, 1919

Eldress Lizzie has been in Portland for several days, having her ears tended to by doctors. It seems strange without her here to lead us into the dining room, and to indicate when the meal has ended. Eldress Prudence takes her place — she is the “Second Eldress” and is in charge of the younger sisters and also those girls who have moved over to the dwelling, as I will when I turn thirteen.

The brethren are working very hard at the moment on brush-making. They make 70 a day, using the raveled horsehair that we girls have prepared. When they finish, they will have almost a thousand brushes to sell. And in the sisters’ shop, they are working on cloaks. We need the money for taxes.

(Of course if they had more candy-makers, it would be a help, I think.)

Gloria has no more news for me of Daniel. His desk, beside Eli, is still empty, and when I ask Gloria, she simply shrugs. At recess she spends her time with the other girls from the world, Louise and Marian. They ignore the Shaker girls like me.

Thursday, March 13, 1919

Brother Delmer went to Portland in the automobile and brought Eldress Lizzie back to Sabbathday Lake. She is feeling very cheerful with her ears no longer aching, and we are glad to have her back with us.

The boys have a sled that they are allowed to use when they have recreation time. They come f lying down the hill behind the schoolhouse, shouting and laughing. We can see, and even hear, them from the windows of the girls’ shop. I pointed out to Sister Jennie that Mother Ann said males and females are equal — it is an important part of the teachings — and so we girls should have a turn with the sled.

She is thinking about that, and she may ask Eldress Lizzie to discuss it with Elder William. I think he will agree, because it was he who took the girls on a sleigh ride and so he has seen how much we enjoy being out in the cold, fresh air. And we do not shout as the boys do.

I think Daniel would enjoy the sledding.

It is almost spring, but in Maine the date of spring doesn’t mean much. It is still cold, and there is still a great deal of snow on the ground. On March 30th we will start Daylight Savings Time and it will be light at suppertime.

Monday, March 17, 1919

It is not that I am too young for candy-making. Susannah has been doing it, and she is just my age! She lives in the girls’ shop and sleeps in the retiring room across the hall, with Elvira Brooks and the Holt sisters. Ordinarily I like Susannah. But lately she has been commenting too often about what hard work it is, making taffy and caramels.

And not only that, but Elvira and Polly are both starting piano lessons! They go, one at a time, to practice in the good room while the others of us have to listen to them from the room where we are doing our endless knitting. Their piano playing is just as bad as my knitting, maybe worse!

I would like piano lessons! And I would like to make candy! Instead, Sister Jennie is teaching me to sew so that I can make my own dresses as all the older girls do. I hate sewing and I hate knitting and I hate ironing and …

Oh, hating is a terrible sin, I know. So is envy. One of the seven deadlies. But still!

Saturday, March 22, 1919

I opened my mind to Sister Jennie today and told her about all the hating and envying I had been feeling. I thought she would lecture me and I thought that I deserved the lecture.

She did, at first, remind me of one of Mother Ann’s teachings, one we girls had learned in Sunday School: “Labor to make the way of God your own. Let it be your inheritance, your treasure, your occupation, your daily calling.”

I promised I would try.

And then, instead of a lecture, she taught me a new song! We sang it together. To be honest, Sister Jennie does not have a very pretty singing voice, not like the four sisters over at the Canterbury Shaker community in New Hampshire who have made a quartet and take the Shaker songs out to the world.

But Sister Jennie and I sang together …

I will bow and be simple

I will bow and be free

I will bow and be humble

Yea bow like the willow tree

… and I realized that the lecture I deserved was in the song itself.

I must learn to bow.

Tuesday, April 1, 1919

We girls sat in the wrong desks at school today, and then said “April Fool!” when Sister Cora looked askance at us. She didn’t laugh, just directed us sternly to our assigned seats.

In the afternoon, Eliza used the telephone at the girls’ shop (Sister Jennie was busy elsewhere and didn’t know) to call the trustees’ office and tell Brother Delmer that our pipes were frozen. He was quite surprised because the weather has been warming and the snow is even beginning to melt a bit. But he came immediately with his tools. And he did laugh when we all cried, �

�April Fool!”

After supper, back at the girls’ shop, we had one more joke to play. Susannah had secretly brought candy wrappers from the candy-making room in the sisters’ shop, where she had been working. She and I carefully wrapped the stones that I had saved for such a long time, the ones I pretended were my family. I saved only one, the little pink one that I called Lucy for my baby sister. The others didn’t seem important keepsakes anymore. There were so many of them, because I had added stones for each of the sisters and the girls as well. My family had become very large! And now we wrapped them each in a candy wrapper, and after supper we announced we had a surprise, and passed them around as all the girls and Sister Jennie settled into their chairs to start the evening of fancywork and story reading.

Of course they discovered the trick very quickly. We announced “April Fool!” and gathered up the stones. Sister Jennie shook her head at our foolishness.

Then she opened her book and began to read aloud. But it was The Five Little Peppers, which we had finished such a long time ago! When she saw our faces, she said, “April Fool!” and picked up the real story.

Tuesday, April 8, 1919

Yesterday afternoon, after school, I walked up the road to the trustees’ office because Dr. Hayden, the dentist, had come, and he was to examine my teeth. Sister Ada Frost was just coming out when I got there and she was looking a little pained, so I expect she had needed a filling. (I was lucky. I didn’t.)

Just as we were passing each other on the steps at the entrance, we heard a noise above. Sister Ada and I both looked up. There, in the sky, a V of geese was flying noisily past. Perhaps, Sister Ada said, they would remain at Chosen Land for the summer instead of going farther north. She said there are always waterfowl on Sabbathday Lake in summer.

I have never been here in summer. But the other girls say that we can swim and pick berries and have picnics.

Walking back to the girls’ shop after my time with Dr. Hayden, I noticed that the willow trees are beginning to turn pale green. The tall oaks and maples are still stark, with bare branches against the sky. They will not have leaves for another month. The willows are always the earliest, brightening that way when there is still snow on the ground, reminding us that spring is coming, that the earth is renewing itself.

At home, at my first home, in the world, Mother always brought in bare forsythia branches and placed them in water so that they would burst into their yellow bloom for Easter. She called it “forcing” — making them bloom early.

No one is forcing the willows. They are eager. For the first time I noticed how they do curve and bow gracefully, their pale green looping down toward the piled snow.

Saturday, April 12, 1919

Yesterday afternoon we could hear the boys shouting, “Ice out! Ice out!” Everyone in Maine knows what that means. The thick ice coating the lake is beginning to crack and break. Wide holes are opening and you can see the dark, cold water. From here we could hear the sound last night as the ice chunks moved and ground against each other.

The snow has melted so much that the top of the high grass is exposed. The sky is blue today, with high, thin clouds here and there.

This morning, as we cleaned our rooms, we girls kept going to the windows and looking out at the fields beyond the barn. The men and boys are turning the animals out. They have been cooped up in their stalls for months. Now they step out into the air, curious and excited. Some of the young cattle run, kicking their heels up. Their breath comes in steamy bursts.

Sister Jennie came in to remind us to go back to our sweeping, but then she, too, went to the window and watched. There are so many of them! They stream out, urged forward by the men and boys, who shout at them and slap their rumps. Then they move across and out. The fields go on and on. By evening, Sister Jennie says, they will come back up to the rear of the barn for hay that will be strewn for them. But now, in daytime, they explore the outdoors they have not seen for months. They nudge at the snow, pull at the old grass, run at each other as if in play.

After the cattle, the horses emerge: the two big draft horses, and the two sleeker driving horses, then the old one, the one that doesn’t work anymore, that plods out and looks around. And the mules, too. They all still have their heavy winter coats but soon they will shed, rubbing themselves against the bark of trees.

We girls are not allowed to go down to the barn because that is the boys’ place. But after dinner, in the afternoon, we foolishly played at being cattle and horses, galloping up and down the road, snorting and tossing our heads. The sisters, out and about at their tasks, watched us and laughed.

Wednesday, April 16, 1919

It is ten in the morning, and we are neither in school nor at work. Some of the girls are crying. All of us are very frightened. There is nothing we can do but wait, and watch, and pray, because a frightful thing has happened.

Yesterday was such a beautiful day … so springlike. We watched the young cattle lope out across the fields, so happy to be free of the barn. None of us had any hint of what was to come. There were clouds in the sky, and the weather grew chilly at suppertime. No one gave it a thought. But sometime in the night, the wind came up, and with it, snow. In mid-April! It is very rare. It began to snow and grew worse and worse, with the wind howling. It became a blizzard. By morning, when we woke, we could see nothing outside — just the whirling white. From the girls’ shop (I am looking through the window now) the brick dwelling next door is not visible. There is nothing visible but snow.

In the past, during snowstorms, the boys delivered food to the girls’ shop so that we would be warm and fed before they shoveled out the paths. But this morning they could not. Sister Jennie had a call on the telephone, very early. The men and boys have all gone out to try to find and save the animals. Can you imagine! In this blinding snow and bitterly cold wind, they have made their way, calling to one another since they can see nothing, out into the fields. Some of the men are too elderly to undertake such a dangerous job. Elder William will come here very shortly and lead us all over to the dining room and kitchen, where we will be warm and can help prepare food for those who make their way back.

We are afraid for the men and boys who are out there, blindly searching in the howling blizzard. We are afraid for the animals, who are frightened and cold and unfed.

And we are afraid for Chosen Land. If we were to lose the herd of cattle — and the horses —

I hear Elder William stamping his feet on the porch. I must hurry.

Later. 2 p.m.

I tucked my journal inside my jacket and now I have it here, in the dwelling. Sister Jennie said I might use this time to write. “Yea,” she said, when I asked permission. “This is our history you are writing.”

The wind has died a little, though the snow still swirls. Through a window I can see a corner of the barn. When we came this morning from the girls’ shop, it was still blowing and impossible to see. Elder William led us. We all held hands and formed a line, the littlest girls in the middle and Sister Jennie at the rear. Lillian Beckwith cried and cried, she was so frightened, but she made her way bravely, holding the hands of the girls on either side.

Now we are all gathered here, waiting, waiting. Eight cows and two horses have been found and returned to the barn. The men and boys come in now and then to get warm. We have soup for them, and fresh-baked bread, and hot cider or cocoa to drink. The whole day is upside down, with no ringing of the bell for meals. The searchers come and go. We warm their coats and boots at the woodstoves. Beards and eyebrows are coated with ice, and their cheeks are crimson. There is no merriment, only worry and weariness.

A little while ago a cheer went up, suddenly. The two workhorses had found their own way back and appeared at the barn door. This is a heartening thing. But the men and boys wrestled themselves into their coats and boots and went back out again. There are many more animals still to save.

Later still. 7 p.m.

They are all in the barn! None of the animal

s have been lost! The last of them was brought in not thirty minutes ago, by Brother Delmer. We then had a meal together, after kneeling by our chairs and giving thanks. For the first time since I have been here, there were strangers in the dining room. Men and boys from the farms in the area had shown up to help throughout the long day, and we fed them all.

They came from miles away, some of them, urging their own horses through the blizzard because they knew we needed help.

We gave thanks for all of it, for the animals and their safety, for the world’s strangers who helped us, for our warm dwelling and nourishing food, for the end of the snowstorm and the bright moon rising now over the lake.

And I gave thanks for something else. I didn’t notice this at first. But Sister Jennie came to my chair and leaned down and whispered to me. When I looked, glancing over to where the weary men and boys sat silently eating, I saw it was true. I bowed my head right there at the table, and murmured a thank-you to a Father-Mother God who looked, in my imagination, a little like Caroline and Walter Pierce. I expect that is sacrilegious and Mother Ann would be shocked. But it is what I saw, in that moment, when with a heart filled with relief and gratitude, I realized that Daniel had returned to Chosen Land.

Sunday, April 20, 1919

It is Easter.

The spring snow did not last. We can see grass again. Crocuses are up, and the lake is rippling with water. There is a breeze, and the willows bow and bend and sway.

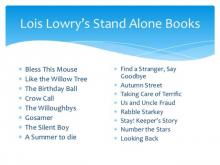

The Willoughbys

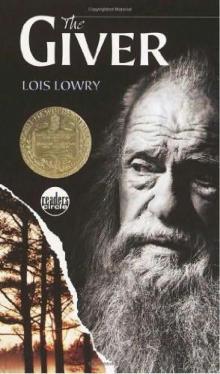

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver