- Home

- Lois Lowry

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Page 2

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Read online

Page 2

Daniel and I are alive, but Daniel hates the entire world and will not speak, not to me or to anyone.

He and I are at Uncle Henry’s farm now. It is a cold and crowded place. I overhear Uncle Henry and Aunt Sarah talking in low voices filled with both sorrow and anger.

I do not know what will become of me and Daniel.

I can remember the last words my mother said to me, but I cannot bring myself to write them down.

I had my birthday just twelve days ago. I am eleven years old. I feel one hundred.

Friday, October 18, 1918

In Rockland they have turned a large hotel, the Narragansett, into an emergency hospital, and anyone of any class or religion may go there, without reference to their financial circumstances. Women from eight different churches have become an emergency hospital committee, and the Superintendent of Schools has announced that the city’s school teachers will now become workers in the hospital office, kitchen, and sterilizing department. The world has turned upside down. Nothing will ever be the same.

The Courier Gazette has printed a list of needs: towels, sheets, blankets, and babies’ cribs. Reading it made me remember Lucy’s little crib at home, and I wept. I wondered what would become of our house. I suppose when all of this ends (surely it will end!) some other family will move in and pay the rent. What of our things? We did not have valuable things but there were things we loved. Mother’s good dishes, with pink flowers painted around the edge. The tall clock, and the umbrella stand where once I thought I would hide Daniel’s shoe. What of them?

We left so quickly and took so little. It is a blur in my memory. Uncle Henry made whatever arrangements had to be made. But he was silent, and rushed. I could tell he wanted to get away. It had become a house of horror. He hurried us, and I left with only the clothes I wore and a small satchel with a yellow scarf that Mother had knitted for me and my Sunday School shoes (why did I take those, I wonder? But I was not thinking clearly) and my beloved book, The Secret Garden.

It happened to Mary Lennox, too. In the book, I mean. She became an orphan and was taken from her home and sent to live with an uncle. When Emily Ann and I were reading it together and acting it out, it seemed like make-believe, and we were very dramatic, each of us weeping wildly when it was our turn to be Mary, while the other held the book and tried to look serious. But we giggled, both of us.

Mary’s uncle, Archibald Craven, in the book, seems very uncaring. Reading it, I thought he was cruel. Now, though, watching Uncle Henry, whose face is stern and lined, who seems uncaring, I realize something. He is grieving. He loved my mother. She was his only sister. But men cannot weep. They must do things. They must make arrangements, take care of things, make plans, figure things out. Uncle Henry must mourn his sister and at the same time figure out where to put two more children, and how to feed them (for there is little money), and he must also answer to his very angry wife, who doesn’t want us here (I have heard her say just that).

And he must find a way to deal with Daniel, who either falls sullenly silent, or talks back rudely when asked to help with chores. I don’t blame Daniel, really, because I have seen how the boys — our cousins — mock him for not knowing how to do things on a farm. But I fear Uncle Henry will have to thrash him. Father would have, I know. With his belt.

I try to help but am always in the way. Aunt Sarah says that she is forever tripping over me. The twins, Margaret and Mabel, tried at first to be sweet and loving, but now they are cross because I am sleeping in their room and taking the space where they always played with their dolls. And I am wearing their clothes, as well! They don’t like that. But what am I to do?

I wander, often. I button up my jacket and walk down the lane and through the meadow. The air is getting cold now. The wildflowers have all died back and the grass snaps under my feet. Uncle Henry’s workhorses come to the fence hoping I have brought them a treat, and sometimes I find forgotten apples on the ground that I can feed to them. One morning there was a thin layer of ice on their water trough. I poked it with a stick and broke through easily. But soon the water will be frozen solid. Winters are hard here. Uncle Henry and his boys (and Daniel, if he ever returns to himself) will have to carve a path through snow to the barn and carry water and feed for the animals.

Schools are still closed everywhere. The sickness does not seem to end. It is terribly frightening. At Swans Island, they say, out of a population of 800, there are 260 who are desperately ill.

The sky is almost always gray. I wonder if my mother looks down on me.

I will tell you now, the last thing she said. For a while it was too hard for me to remember it or say it. But now I think of her so often, and of that last day. Father had come home from work tired, and didn’t want supper, and then very suddenly he became terribly ill. Mother tended him and would not let us near. She was trying to keep us safe. Daniel and I tried to help a bit. I cooked what food I knew how to, and Daniel tended the fires in the woodstoves.

Then the baby, too, was ill, all of a sudden. The doctor did come, once, but he just shook his head and went away again. He seemed so tired. And so did Mother. But she told me what to do: to bring the food to the door of the bedroom, to leave it there on the floor and go away. I brought basins of water, too, and cloths, and left them there for her, but she always told me to move away, not to come near to her. So I would leave the tray, knock on the door, then stand at the top of the stairs and talk to her from there, when she opened it a crack to take the things.

Lucy never cried, not once. It would have made my heart leap to hear Lucy cry, but she was silent in her sickness.

I could see when Mother fell ill. She still came to the door of the room where they were and spoke to me, but she was weakened and feverish. It was more than just tired. Sometimes her mind wandered.

I knew the doctor would not return, but Daniel told me to run next door and ask Mrs. O’Brien to come and help us. She has always been such a kind and caring neighbor. But she came to the door twisting her hands in her apron, and said no. She said she was sorry but there was nothing she could do.

I telephoned Mrs. Walsh, Emily Ann’s mother. She said the same thing but that she would pray for us.

I went and stood on the front porch, looking down toward Stevens Avenue with a feeling of hopelessness. Ordinarily there would be people walking, horses and buggies, occasionally an automobile. But now it was empty. If I had called out, “Help us!” there would have been no one to hear it. The houses in the neighborhood were all silent, with shades drawn. A dog came past slowly, looking back and forth, as if it had become lost.

Finally, not knowing what else to do, I went into the kitchen and made more tea. I put it into the Blue Willow teapot, and then put that on a tray with a clean cup and saucer. I balanced it carefully, walking as if I were serving a lovely luncheon, and took it upstairs. Carefully I set it down outside the door to Mother and Father’s room, and knocked, as I had been doing. Then I stood back.

Mother came after a long moment. She smiled a little at me.

“You’re a lamb,” she said. “You’re my dear little lamb.”

She looked down at the teapot, sighed a bit, and then closed the door, leaving the tray as it was.

After that I did not see her again, and there came no reply to my knocks. We waited awhile. Then Daniel said we must try again to find help. He telephoned Uncle Henry, who said he would come as quickly as possible. Daniel and I sat silently in the living room for hours, waiting. The tall clock was no longer ticking. Father was the one who had wound it every evening, and now its metal hands were still. It was evening when at last we heard Uncle Henry’s steps on the front porch. He came in and Daniel and I followed him up the stairs.

But by then it was too late. When he opened the door to the room, I cried out at what I saw. Daniel’s face turned white. He came and put his arms around me. He held tight to me, but it felt as if the hallway where we stood was spinning and whirling. I remember nothing after that.

<

br /> Saturday, October 19, 1918

Walking in the lane beside the farm this morning, I found five stones that I have put into my pocket. The two larger ones are the mother and the father. My mother and father: Caroline and Walter Pierce. Then there is a slightly smaller one, grayish, with a jagged stripe and a rough edge: That is Daniel. A sweet, tiny pinkish one is Lucy. And I am an ordinary stone. There is nothing special about me, Lydia Amelia Pierce, except that I am a part of this little family in my pocket.

I stayed outdoors too long and Aunt Sarah was very angry when I went back. I had promised to help with the bread making, but I forgot. Margaret and Mabel helped but that left no one to look after Willie, who is two, and he got into Aunt Sarah’s knitting and pulled it all apart. So she was in a rage.

And Daniel left his chores undone as well.

Later I heard Aunt Sarah say to Uncle Henry that “they” must go. By “they” she means me and Daniel. I could hear Uncle Henry sigh but he did not argue with her. Listening, I touched my fingers to the stones in my pocket and hummed loudly so that I could put her angry voice out of my thoughts.

But I heard her tell him to take us to Sabbathday Lake, and so I think she means for him to drown us. Surely he would not do that to his dead sister’s children! But I did not hear him say no to his wife’s command.

Sunday, October 20, 1918

Daniel told me he hopes the war in Europe will last and last so that when he is old enough he can go and join up. He is only fourteen. In February he will be fifteen. But that is still not old enough for the army, and anyway people say now that the war will end soon.

There is little talk of it anymore. A year ago, when Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, of Portland, lost their son, Harold, in a battle in France, Mother took a bouquet of flowers to their home. He was the first soldier from Maine to die in the war, and everyone spoke of it in shocked and saddened voices. Then there were so many others.

But when the influenza began, we forgot the war because the horrors moved into our own homes. And now Daniel says he would like to join up. Anything, he says, to get away from Uncle Henry’s farm.

He does not talk to me much but I found him out behind the barn, whittling on a piece of wood, when I took a walk to escape the twins bickering and Willie howling and Aunt Sarah complaining. Uncle Henry and the older boys were out repairing the fences, and Daniel should have gone to help, but instead he was crouched behind the barn. I asked him if he knew where Sabbathday Lake was and he shrugged and said no.

“I think Uncle Henry is fixing to drown us, the way he does kittens,” I said.

Daniel just laughed a bit and carved at his stick. “He doesn’t have to drown me,” he said. “If he wants me gone, I’ll go, and glad to.”

“But where?” I asked, for I had been thinking the same way myself. I have no wish to stay at a farm where I am not wanted.

That’s when Daniel said about the war, and the army. He could lie about his age, he said. Others have. Maybe in the spring he would try.

“I have to wait till spring because I’ve got no winter shoes, not good enough for walking far.” He held up one foot and I could see that his shoes were in poor shape, with one sole loose and aflap. Poor Daniel. That he would think war might be better than the life he had! It made me sad — and a little angry, too, that he would leave me behind without a second thought. But he was not really the Daniel I had known. When I looked closely at him, I could see he looked untended, his clothes filthy, his hair needing a cut. I suppose I am much the same, in my borrowed dress and torn stockings stuck with twigs and burrs. We have been only ten days here at the farm and already we look like the orphans that we are, disheveled and dirty.

Monday, October 21, 1918

Tonight at supper Uncle Henry told Daniel and me to get our things together because he would be taking us someplace in the morning. He did not say where. But I think if he were planning to drown us like kittens, he would not tell us to bring clean underclothes.

United Society

of Shakers

Sabbathday Lake, Maine

Tuesday, October 22, 1918

So much has happened and I hardly know where to begin.

We left in the middle of the morning, this morning, after the farm chores were done. We were dirty yet. Daniel didn’t care. But I felt ashamed. No matter where we were going — and I still didn’t know — I did not want to arrive smelly and smudged. But Aunt Sarah would not let me have a bath. I washed my face and hands at the sink, as I have each day. But truly, I was not clean, not at all.

The well is always low by fall, especially after a dry summer, so I understood her reason. If I had a bath, it might mean a long wait until there was water again, enough to wash the dishes and the clothes. And so I simply scrubbed what I could and cleaned my nails. I put on the dress I had worn from Portland when we left there, for I could not take the twins’ clothes and wouldn’t have wanted to.

It was eight miles to the northwest. A beautiful day, cool, with a breeze, and the trees all red and gold as they are in October, with many leaves on the ground already. The horses are eager in cool weather; they snort and stamp. We had brought some food and had our lunch along the way, stopping by a stream where the horses could have a drink. It was only when we stopped that Uncle Henry began to talk, suddenly.

“You know I’m taking you to the Shakers,” he said.

But Daniel and I just looked at each other. Of course we didn’t know that. We didn’t even know what it meant. Shakers?

“The Shakers at Sabbathday Lake.” Uncle Henry carved his apple with his knife. He ate a piece, and wiped his beard with the napkin Aunt Sarah had placed in the basket with the food. He looked off into the distance, across the hills and woodland that bordered the road. “Your mother and I learned to swim at that lake when we were your age,” he said.

“Were the Shakers there then?” I asked him. I pictured Uncle Henry as a boy Daniel’s size, and my mother, his sister, Caroline, younger. In my mind I could see them playing on the shore of a lake, and surrounding them was a group of something mysterious, shaking. I decided Uncle Henry was telling us a ghost story, as he sometimes did. “Were you scared?” I asked.

He reached over and smoothed my hair. “You look like your mother,” he said, and I could see that he felt both sad and kindly at once.

“I know,” I told him.

Daniel became impatient. He scribbled with a stick in the dirt. “What are the Shakers?” he asked gruffly.

Uncle Henry sighed. “Their village is up ahead. We’ll be there soon. They’re expecting us.”

“And you’re leaving us there.” I said it in a way that wasn’t a question, because I knew it was true.

“I’ll try to come back to see you. But you understand that we can’t keep you with us.”

I nodded. I understood. It was simply that Uncle Henry and Aunt Sarah didn’t have enough. Not enough room. Not enough money. Not enough food. As for Daniel, he just looked away.

Uncle Henry began gathering the scraps from lunch. He tossed his apple core into the bushes. “The Shakers take in children and raise them. They’re fair and hardworking and honest. You’ll get good care, and an education. You’ll get what I can’t give you.”

He held out his hand to help me back up into the wagon. Daniel hoisted himself up on the other side. Uncle Henry took a handkerchief from his pocket and wiped his face as if he were sweating, the way he did during farm work. But I could see he had tears in his eyes. He settled himself in his seat and jiggled the reins so that the horses started up.

“They’ll seem strange to you at first. They have some strange customs. It’s their religion.”

“My friend Marjorie Fallon, in Portland? She’s Catholic. Catholic is a strange religion.”

Uncle Henry laughed a bit. He reached over and drew me to him, put his arm around me, for the first time since he came for us in Portland. He was so stern then, so silent. Now there was a softer part to him showing, and I knew he loved

us and was sorry to send us away.

“I should have said different, not strange,” he explained. “But you’ll grow used to their ways. I had a hired man once, Levi Mitchell. Raised by the Shakers. He didn’t stay there, once he was grown. Left there to make his own way, and worked for me for a while. Best worker I ever had. Careful, and quiet. Always bowed his head for a minute before he ate. He could read and write and figure, and he knew farm work. He said the Shakers taught him all of it, and he had nothing but good to say of them.

“I was thinking of Levi when I telephoned them to ask if they could take you.”

“But he didn’t stay,” Daniel said suddenly. It was the first he’d spoken in a while.

“No, he decided he wanted to be in the world. That’s what the Shakers call our way of life.”

“I don’t want to stay,” Daniel said.

Uncle Henry looked at him. “You need a place, son. You need a home. They’ll give you that for now. When the time comes, you can decide.”

Daniel looked away, and I could tell that he had already decided. No one said anything. The horses plodded along, and when we rounded a curve in the road, we could see, first, a huge brick building, then the others, all of them white, that were near it. We could see cattle in the fields behind the barn — and glimpses of the lake beyond. An orchard spread out on our left, and beyond it what looked like a schoolhouse. It seemed to be a whole village, but quite small, and it was amazingly tidy. It made me think of a toy village, built for dolls.

“Here we are,” Uncle Henry said.

Now I am sitting in the room where I am to live. A woman brought me here. Other girls will share this room with me, but they are not here now. Their beds are neatly made, and everything is so clean, so in order. At home in Portland, our house was clean, but nothing like this. I sit here for a moment trying to understand the difference and I realize there is no decoration here. At home, there were pretty scarves on the bureaus, pictures on the walls, framed photographs, a vase of flowers, a stack of magazines, a bowl of mints. There was my lamp with the shepherdess looking into the pale green meadow.

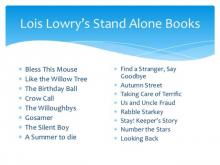

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver