- Home

- Lois Lowry

Anastasia Krupnik Page 2

Anastasia Krupnik Read online

Page 2

Mrs. Westvessel looked terribly sad. "I can tell that you did, Anastasia," she said. "But the trouble is that you didn't listen to the instructions. I gave very, very careful instructions to the class about the kind of poems you were to write. And you were here that day; I remember that you were.

"Now if, in geography, I explained to the class just how to draw a map, and someone didn't listen, and drew his own kind of map" (everyone glanced at Robert Giannini, who blushed—he had drawn a beautiful map of Ireland, with cartoon figures of people throwing bombs all over it, and had gotten an F.) "even though it was a very beautiful map, I would have to give that person a failing grade because he didn't follow the instructions. So I'm afraid I will have to do the same in this case, Anastasia.

"I'm sorry," said Mrs. Westvessel.

"I just bet you are," thought Anastasia.

"If you work hard on another, perhaps it will be better. I'm sure it will be better," said Mrs. Westvessel. She wrote a large F on the page of poetry, gave it back to Anastasia, and called on the next student.

At home, that evening, Anastasia got her green notebook out of her desk drawer. Solemnly, under "These are the most important things that happened the year that I was ten," in item three, she crossed out the word wonderful and replaced it with the word terrible.

"I wrote a terrible poem," she read sadly. Her goldfish, Frank, came to the side of his bowl and moved his mouth. Anastasia read his lips and said, "Blurp blurp blurp to you too, Frank."

Then she turned the pages of her notebook until she came to a blank one, page fourteen, and printed carefully at the top of the right-hand side: THINGS I HATE.

She thought very hard because she wanted it to be an honest list.

Finally she wrote down: "Mr. Belden at the drugstore." Anastasia honestly hated Mr. Belden, because he called her "girlie," and because once, in front of a whole group of fifth grade boys who were buying baseball cards, he had said the rottenest, rudest thing she could imagine anyone saying ever, and especially in front of a whole group of fifth grade boys. Mr. Belden had said, "You want some Kover-up Kreme for those freckles, girlie?" And she had not been anywhere near the Kover-up Freckle Kreme, which was $1.39 and right between the Cuticura Soap and the Absorbine Jr.

Next, without any hesitation, Anastasia wrote down "Boys." She honestly hated boys. All of the fifth grade boys buying baseball cards that day had laughed.

"Liver" was also an honest thing. Everybody in the world hated liver except her parents.

And she wrote down "pumpkin pie," after some thought. She had tried to like pumpkin pie, but she honestly hated it.

And finally, Anastasia wrote, at the end of her THINGS I HATE list: "Mrs. Westvessel." That was the most honest thing of all.

Then, to even off the page, she made a list on the left-hand side: THINGS I LOVE. For some reason it was an easier list to make.

Her parents were having coffee in the living room. "They're going to find out about the F when they go for a parent-teacher conference," thought Anastasia. "So I might as well show them." She took her poem to the living room. She held it casually behind her back.

"You guys know," she said, "how sometimes maybe someone is a great musician or something—well, maybe he plays the trumpet or something really well—and then maybe he has a kid, and it turns out the kid isn't any good at all at playing the trumpet?" Her parents looked puzzled.

"No," said her father. "What on earth are you talking about?"

She tried again. "Well, suppose a guy is a terrific basketball player. Maybe he plays for the Celtics and he's almost seven feet tall. Then maybe he has a kid, a little boy, and maybe the little boy wants to be a great basketball player. But he only grows to be five feet tall. So he can't be any good at basketball, right?"

"Is it a riddle, Anastasia?" her mother asked. "It seems very complicated."

"What if a man is a really good poet and his daughter tries to write a poem—I mean tries really hard— and the only poem she writes is a terrible poem?"

"Oh," said her father. "Let's see the poem, Anastasia."

Anastasia handed the poem to her father.

He read it once to himself. Then he read it aloud. He read it the way Anastasia had tried to, in class, so that some of the words sounded long and shuddery. When he came to the word "night" he said it in a voice as quiet as sleep. When he had finished, they were all silent for a moment. Her parents looked at each other.

"You know, Anastasia," her father said, finally. "Some people—actually, a lot of people—just don't understand poetry."

"It doesn't make them bad people," said her mother hastily.

"Just dumb?" suggested Anastasia. If she could change, under "Why don't I like Mrs. Westvessel?" the answer "Because I'm dumb" to "Because she's dumb," maybe it wouldn't be such a discouraging question and answer after all.

But her father disagreed. "Not dumb," he said. "Maybe they just haven't been educated to understand poetry."

He took his red pen from his pocket. "I myself," he said grandly, "have been very well educated to understand poetry." With his red pen he added some letters to the F, so that the word Fabulous appeared across the top of the page.

Anastasia decided that when she went back to her room she would get her green notebook out again, and change page two once more. "I wrote a fabulous poem," it would say. She smiled.

"Daddy, do you think maybe someday I could be a poet?" she asked.

"Don't know why not," he said. "If you work hard at it."

"How long does it take to make a whole book of poems?"

"Well, let's see. That last book of mine took me about nine months."

Anastasia groaned. "That's a long time. You could get a baby in nine months, for pete's sake."

Her parents both laughed. Then they looked at each other and laughed harder. Suddenly Anastasia had a very strange feeling that she knew why they were laughing. She had a very strange feeling that her list of THINGS I HATE was going to be getting even longer.

2

The rats. So they were going to have a baby.

Anastasia had been angry a lot of times.

She had been angry the day that she came down with the flu and had a temperature of 103° and had to miss the special Children's Concert that the Boston Symphony was doing, and her parents gave the tickets to the terrible Truesdales who lived in the upstairs apartment.

She had been angry at the paperhanger who insisted on wallpapering her bedroom with the wallpaper rightside up, when Anastasia preferred the way it looked upside down.

She had been very, very angry at the person who stole her new bike when she forgot to chain it to the fence outside of the J. Henry Bosler Elementary School.

But she had never in her life been as angry as she was the evening that her parents told her that they were going to have a baby.

"What are you trying to do, be in the Guinness Book of World Records?" she asked her mother. "You're too old to have a baby!"

"Thirty-five?" her mother asked, with raised eyebrows. "Thirty-five is too old? Thirty-five is going to put me in The Guinness Book of World Records? Come on, Anastasia. Thirty-five is the prime of life!"

"Ten is," muttered Anastasia. "Ten is the prime of life."

"Wrong, both of you," said Anastasia's father. "The prime of life is forty-five. I'm in the prime of life."

"Anyway," added Anastasia, "you don't need a baby. You have me."

"Dumb, dumb, dumb," she thought immediately. "I'm being dumb, again. I'm the only one in the whole world, for pete's sake—the whole world including even my parents—who thinks that I'm important enough to be the only kid in the family."

Her mother sat glumly, examining some burnt umber paint on the back of her hand. Her father rolled his eyes the way he did every time the Patriots missed a first down.

"Yes," he said. "We certainly do have you."

There was a long silence.

"So," said Anastasia, finally. "You're not going to change your minds

?"

Her mother rubbed her middle softly with her paint-smeared hand. "It's too late for that, Anastasia."

"It's a fait accompli," said her father.

"You know I can't understand Greek, Daddy."

"French."

"Well, French, then. I can't understand French either. What's a fait accompli: another word for baby?"

"In this instance I guess it is. A baby boy."

Anastasia hooted. "You guys may think don't know anything, but I do know that you can't tell what kind of baby it is until it's born. What do you mean, a baby boy? Did you consult a fortune teller?"

"Actually," said her mother brightening a little and pouring herself another cup of coffee, "it's really pretty interesting, Anastasia. They have this special test they do, on certain women...."

"What do you mean certain women?"

Her mother blushed. "On women who are thirty-five or older if they're pregnant."

"See?" Mid Anastasia. "See?"

"And," her mother went on, ignoring her, "they did this test on me and it showed that the baby is healthy. A healthy boy."

Anastasia kicked the rung of her chair with one sneaker. She was quiet thinking. Her parents both stirred their coffee at the same time, and sipped, at the same time, as if they'd been rehearsing: one, two, three, stir, and one, two, three, sip.

"You have probably been thinking some about where you're going to put this, ah, baby boy, in this extremely small, extremely crowded apartment," Anastasia said.

"Yes," said her father with interest. "We have been thinking about that. Any ideas?"

"Simple," said Anastasia, standing up. "Very simple. It can have my room. Because I'm moving out. Excuse me. I have to go pack."

She stomped down the hall to her bedroom. In the darkest corner of her closet she found the heavy canvas bag that was left over from her father's days in the Navy; it had KRUPNIK M A stenciled on the side. Once, when she was smaller, her father had put her into it, pulled the drawstring closed, and carried her around the apartment while she giggled.

Anastasia took the orangutan poster from her wall, rolled it up, and put it into the canvas bag. Then she added three pairs of underpants and a box of crayons. Carefully she put in her green notebook and a sweat shirt with a picture of Amelia Earhart. Sadly, she realized that she couldn't pack her goldfish. But her comic books went in, and a box of Kleenex, and a folded program from a performance of Peter Pan. Reluctantly she added her arithmetic book. Then she cleaned her water-color brushes in the glass of muddy water that had been on her desk for a week, put the brushes into her box of paints, and tucked that into the bag. Under her bureau was a rather stale Hostess Twinkle. She added that.

Then she went back to the kitchen. Her parents were still drinking coffee, looking distressed, and talking to each other quietly.

"Excuse me for interrupting. But I would like to have my silver cup, the one with my name on it, that my grandmother gave me when I was born. You don't have to polish it or anything."

Her mother went to the cupboard to look for the cup.

"You know, Anastasia," said her father. "The baby won't be born until March. So there's no need to hurry in making a decision about moving out. I would think that you'd like to stay through Christmas at least."

Anastasia didn't say anything. But she began to think. It would be nice to be around for Christmas.

Her mother was holding the little blackened cup.

"I really should polish this," she said. "You can barely see the name."

"That's another thing," said Anastasia. "What are you going to name this baby?"

"Goodness," said her mother. "We haven't even thought about that. Maybe you have some suggestions..."

"As a matter of fact," said her father, "I think we should give Anastasia the full responsibility for naming the baby. It will be her brother, after all."

"Of course, I won't be here," said Anastasia.

"That's right," said her father. "I forgot that for a minute. Tell you what, though. If by some chance you should decide to stick around, you may name the baby."

"Anything I want?"

"Well," said her mother, "maybe we should..."

"Anything you want," said her father decisively.

Anastasia stood there, thinking.

"Okay," she said, finally. "I'll stick around, and I'll name the baby. You can put the cup back."

She returned to her room and unpacked. Twinkie, paints, arithmetic book, Peter Pan program, Kleenex, sweat shirt, green notebook, crayons, underpants, and orangutan. She put the KRUPNIK M A canvas bag back on the floor of her closet. She had been thinking the entire time she was unpacking.

Then she sat down on her bed, picked up a pencil from the floor, and opened the green notebook to one of the very last pages where nothing was written at all.

In a secret corner, very small, she wrote the name she had chosen for her parents' baby boy. It was the most terrible name she could think of. When she had written it, she smiled and closed the notebook.

3

"Reasons for maybe becoming a Catholic," wrote Anastasia in her green notebook.

1. There are fourteen Catholics in the fourth grade, and four Jews, and everybody else is something else—I don't know what—but whatever it is is not very interesting. So I would make the fifteenth Catholic. And if ever they start a club or something, I would automatically be in it. That would be nice.

2. And I would get a new name. Maybe at about the same time I get a new brother.

Anastasia thought vaguely that probably there were other good reasons for becoming a Catholic. But she didn't know what the other reasons might be; and the ones she had listed seemed good enough.

"I think I might become a Catholic," she said to Jennifer MacCauley, who she hoped was going to be her very best friend in the fourth grade. Jennifer had a lot of things going for her: she had naturally curly reddish-brown hair, a broken-off front tooth from falling down the basement stairs, and more Barbie doll clothes than any other girl in the class.

She also, she had told Anastasia, was before long going to have a new and very impressive name. Right now her name was Jennifer Elizabeth MacCauley. But one of these days, she said, she was changing her name to Jennifer Elizabeth Theresa MacCauley. That was because she was Catholic.

Catholics, Jennifer told Anastasia, were allowed to give themselves an extra name when they were old enough. They were even allowed to choose the name themselves; Jennifer had already chosen Theresa.

That appealed to Anastasia, who had never liked her own name very much, and who had no middle name at all. When her brother was born, she knew, his new name was going to cause—well, maybe not trouble, but talk. It was certainly going to cause talk. It would be kind of nice to get a new name herself at the same time.

"It has to be a saint's name," Jennifer pointed out.

Anastasia wasn't exactly sure what a saint was. But their names seemed okay. Some even seemed spectacular, for pete's sake. She looked at the list that Jennifer showed her.

"Perpetua," she said, reading from the list. "Anastasia Perpetua Krupnik. I like that. I definitely think I might become a Catholic."

"You can't," said Jennifer apologetically. "You're too old."

"What do you mean, too old?" asked Anastasia. "I'm only ten."

"Look," said Jennifer. She opened the top drawer of her desk—they were in Jennifer's bedroom—and searched through the broken crayons, crumpled spelling papers, and half a deck of cards. She found a snapshot and handed it to Anastasia.

"Big deal," Anastasia said, looking at it. "That's just you in a bride's outfit." Secretly, she looked a little harder and was envious. She had wondered, often, what it would feel like to wear a bridal gown. Not that she ever wanted to get married. Or to have a baby, for pete's sake.

"Ha," said Jennifer. "Bride's outfit, my foot. That's my First Holy Communion dress. I was seven. Everyone is around seven when they make their First Holy Communion. After that you're a real Ca

tholic."

"Liar," said Anastasia.

"No, honest," Jennifer said. "Really. You can't be a Catholic unless you do that."

"Is there a law that you have to be seven?"

"I guess so."

Anastasia thought it over carefully. "There can't be," she said, finally. "What if you were on a trip around the world the whole time you were seven?"

Jennifer shrugged. "I don't know," she admitted.

"What if you had leprosy when you were seven?"

Jennifer looked confused.

"What if you were Jewish when you were seven?"

Finally Jennifer said, "Well, sometimes there's something they do in the Catholic Church. They give a disp—, they give a dispen—, a dispensation. That's what they give."

"What's that?"

"It means that you can do something against the Catholic rules."

"So. I'll get a dispensation, then. What do I have to do?"

"I don't know. You have to go to the church, I guess, and talk to the priest."

"Couldn't you do it, Jennifer? Couldn't you talk to the priest and bring my dispensation home for me? Like picking up the homework assignment from Mrs. Westvessel if I'm absent?"

"I don't know, Anastasia."

"For a Catholic, you sure don't know much, Jennifer."

Jennifer looked uncomfortable.

Anastasia sighed. "When do you go to church next?" she asked. "Saturday."

"I'll come with you then, on Saturday. I'll talk to them about getting the dispensation. Probably I can bring it home with me. Then how long will it take to be a Catholic?"

"A while. You'll have to go to catechism classes."

"Well, that's okay. I want my mother to have time to order new nametapes for my camp clothes, since my name will be different."

"You don't have to put your whole name on things. I don't have my whole name on my camp clothes."

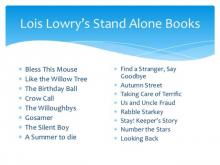

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver