- Home

- Lois Lowry

Your Move, J. P.! Page 2

Your Move, J. P.! Read online

Page 2

The bus appeared, hissing its brakes, and Caroline called, "Come on, J.P.!"

He ignored her again, pretending that she was a total stranger, and boarded the bus. As usual, no seats. J.P. stood wedged between two overweight people and thought about his problem as the bus moved across New York City, stopping jerkily from time to time.

A bookstore would be the solution. And there was a small bookstore just down the street from the Tates' apartment building. J.P. wiggled his left arm up past the hips of the beefy woman next to him and looked at his watch. Three forty-five. Okay. Great. He could get to the bookstore before it closed, and he could invest in a map of London and his future with Angela Galsworthy.

J.P. relaxed. He took a deep breath, standing in his squashed position, and became aware that his height made him level with adult armpits. He wished that more people on the bus had used Sunny Meadow deodorant.

"Too expensive? Jeez, kid, it's only eight ninety-five. Whaddaya expect, that we give books away?"

The bookstore clerk peered over the counter at J.P., who held the paperback guide to London in his hand.

"Could I pay you two dollars now, maybe, and bring the rest in next week?" J.P. suggested politely.

The clerk didn't bother to answer.

"Well, do you have a Xerox machine? Could I just Xerox the map?"

The clerk began sorting through some credit card receipts.

J.P. shifted his weight from one foot to the other. He opened the book again to the map of London. Maybe he could memorize it and then draw it from memory when he got home.

But he realized, looking at the map, that it would be impossible. London was too complicated, even for a phenomenal memory like J.P. Tate's. The streets of New York City made sense, numbered as they were. He could probably draw a New York City map from memory. But London was a haphazard maze of streets, with the river zigzagging through the middle, crisscrossed with bridges. And all the streets had weird names, unlike New York, with its solid, sensible Sixty-ninth and Fifth and Forty-second and Third. London had—J.P. squinted, looking at the tiny print—Chelsea Embankment, Marylebone Road, Montagu Square, Porchester Gardens, Cleveland Terrace, St. John's Wood Road. He closed the book slowly and looked once more at the clerk with what he hoped was a pleading, needy look. But the clerk had turned away and was dialing the telephone.

J.P. put the book on the counter, left the store, and headed home. He could picture Mrs. Hunt tomorrow, staring at him, saying in front of the class, "But, J.P., you said that you had a map of London at home. Weren't you telling the truth?"

He could picture all the guys: Nicholas, Antonio, Kevin, and Danny. They would hoot with derisive laughter, he knew, making a fool of him in front of—

He groaned. He could picture Angela Galsworthy, looking at him in surprise, her pink moist mouth rounded into an open O. She wouldn't sneer and taunt him, he knew, not a soft-spoken, high-class person like Angela Patricia Galsworthy; but she would never care for him again. She would turn her back on him forever. He would become, for Angela Galsworthy, The Boy Who Had Lied.

Caroline was sitting on the front steps, her schoolbooks beside her, looking at baseball cards with little Billy DeVito, who lived on the first floor.

"Where did you go?" she asked. "You got off the bus when I did, but then you disappeared."

"Bookstore," J.P. said tersely.

"Oh." Caroline turned back to Billy, who had handed her a new card, and she examined Reggie Jackson admiringly.

"Caroline," J.P. said suddenly, "can you loan me seven dollars?"

She stared at him. "Seven dollars? What do you think I am, a bank? I don't have seven dollars."

J.P. sighed. "Is Mom home?" he asked.

"Of course not. It's only four-fifteen. She never gets home from work till five-thirty. Anyway, she wouldn't lend you seven dollars. She was complaining this morning that she can't afford to pay the whole phone bill this month. Remember, she said if we call Dad in Des Moines any more, we have to do it collect?"

J.P. remembered. "Yeah," he said gloomily.

"What do you need it for, anyway?" Caroline handed the pack of baseball cards back to Billy and looked up quizzically at her brother.

J.P. started up the steps. "I need to buy a map of London," he told his sister. Then he looked back at Billy DeVito, who was patiently sorting his baseball cards. "Billy, do you by any chance have a map of London?"

Billy looked up at him. "No," he said, cheerfully. "But I have two Oil Can Boyds."

3

"It's because of that new girl, isn't it? Isn't it?" Caroline asked as she trudged up the stairs behind J.P. "Tell the truth. It's because of that girl from England. What's her name—Andrea?"

J.P. didn't say anything. He rummaged through his pocket for the key, opened the door, and entered the apartment. Caroline followed him, still talking. "Alexandra? Is that her name? Come on, J.P. Talk."

J.P. flung his backpack onto the couch and began pulling open the drawers to his mother's desk in the living room. He found a packet of maps and slipped off the rubber band that held them together.

New Jersey.

Pennsylvania.

Connecticut.

And a guide to New York museums. Great. Just great. He frowned and tossed them back into the drawer.

"Mom doesn't have a map of London," Caroline announced from the kitchen, where she was pouring herself a glass of milk. "You're wasting your time. You want some milk?"

J.P. grunted, nodding his head; Caroline poured a second glass and handed it to him.

"I can get you one," she said.

"Get me one what?" asked J.P. "You already got me a glass of milk." He wiped the milk off his upper lip with the back of his hand. "Thank you," he added.

"I can get you a map of London. Tell me her name, though. She's really pretty."

J.P. stared at her. "Her name's Angela Patricia Galsworthy," he said slowly. "Can you really get one?"

Caroline nodded. "What time is it?"

"Four twenty-seven. Can you really get one?"

"Yeah, but I have to hurry. Wait here. Rinse the glasses, okay?"

J.P. nodded, watching her pull on the jacket she had just dropped on a chair. Sometimes Caroline was okay after all.

His sister dashed through the door, and he could hear her feet clattering back down the stairs. He rinsed out the milk glasses, picked up his backpack, took it to his room, and removed his schoolbooks. There was The Prince and the Pauper; they had to read two more chapters tonight. That dumb prince was hanging out at London Bridge trying to figure out how to get back to the palace. Where had Angela said London Bridge was? Near the Tower of London. J.P. tried to remember the map he had examined at the bookstore. And what was the name of Angela's street? Church Street? No, it was more interesting than that—more English. Old Church Boulevard? No. Old Church Crescent—that was it.

Old Church Crescent. What a great name for a street. A perfect place for someone named Angela Galsworthy to live.

J.P. looked around his room. It wasn't a bad room. It wasn't even an unusually messy room; it was cluttered, sure, but it was organized clutter. Every tabletop and desktop was covered with his projects: there was a broken radio, with its disassembled parts carefully arranged so that he could put them back together when he figured out what was malfunctioning; there was a chess set, carefully set up for the game that he'd been conducting with Hope Delafield. J.P. glanced at the few pieces left on the board, trying to remember what dumb move he had made that had caused the checkmate. On a table near the window was an invention he'd been working on for months, with parts of Billy DeVito's broken electric train, which J.P. had found in the trash after Billy got a new train for Christmas; J.P. was trying to hook it all up so that the cars could carry his pencils and paper clips and erasers, and when he flipped a switch at his desk, the supplies would be delivered right to his fingertips while he did his homework.

Now, suddenly, his project with the toy train seemed stupid. The chess ga

me seemed stupid. The broken radio seemed stupid. And messy, and adolescent. And—well, they all seemed so American.

His address—West Eighty-third Street—seemed stupidly American, and his room seemed stupidly American, and his projects seemed stupidly American, and even his name seemed stupidly American. J.P. wasn't his real name, of course; it was a nickname made from his initials.

His real name was James Priestly Tate. He had always hated it.

But now, suddenly, thinking about his real name—James Priestly Tate—he began to sense that it had a certain ring to it. It sounded like the name of someone who might live on a street called Old Church Crescent. It sounded British.

He looked at himself in the mirror. He raised his chin a bit, tilted his head, and tried to look distinguished. "James Priestly Tate here," he said.

Then he tried to think of something British to add. He remembered the dialogue in The Prince and the Pauper, the same dialogue that he had found so boring and so difficult; now it began to seem—

His thoughts were interrupted by the sound of his sister coming through the front door of the apartment. She slammed the door behind her, and he could hear her drop her jacket on the chair once again. Then she came noisily down the hall toward his bedroom.

J.P. turned to Caroline, still holding his chin in the air. "Mannerless wench," he said.

His sister was holding something in her hand. Quickly she thrust it behind her back. "Quit calling me names," she said, "or I'll tear it up."

"I beg your pardon," J.P. said stiffly. "You have my gratitude. At least you have my gratitude if you have a ma—"

"I do!" Caroline announced with glee, and she held it out to him. "A map of London! I got it at the travel agency in the next block! Free!"

J.P. snatched it from her. " 'Tis somewhat paltry in appearance," he said, "but 'twill do."

" 'Twill do, mildew," Caroline said in a singsong voice. "Quit talking so weird. Now you owe me, right?"

"Right," J.P. said, resuming his normal voice as he began to unfold the map. "I do owe you, Caroline." Then he added, "By Jove."

J.P. was working on his math homework in his room after dinner when his mother called from the kitchen.

"Telephone for you, J.P.!" she called.

He had been absorbed in a complicated problem about two cars—a Porsche and a Lamborghini—headed from Geneva to Monte Carlo—in a race, and who would win by how many minutes if they each went so many kilometers per hour; but the Lamborghini got a late start by a few minutes and the Porsche had a mechanical problem along the way, which required two mechanics working for a total price of 1800 francs, at the going rate of 140 francs per mechanic per hour—so how long did the repair take? You had to figure that out, too. J.P.'s math teacher always tried to make the class super-interesting, and he usually succeeded; half the class would bring in illustrations that they had drawn for this problem, along with the answer.

He hadn't even heard the telephone ring.

"It's a girl, J.P.," his mom whispered when he got to the kitchen and she handed him the receiver. Caroline looked over from the sink, where she was helping with the dishes, and made a silly face.

J.P. stretched the telephone cord into the living room and sat down on the floor with his back against the wall.

"Hello?" he said nervously. It was the first time a girl had ever called him up. Except his grandmother.

"This is Angela Galsworthy, J.P.," the waterfall voice replied.

"Right. I mean, yeah. I mean, hi."

"Hi. I found your number in the telephone book. I was terribly surprised that it was there: J. Tate. It didn't have the P, just the J."

"Well, actually," J.P. explained, "J. Tate is my mother. Her name is Joanna, but she didn't put her whole name in the book because if some weirdo sees it's a woman, he might make weird phone calls."

"Oh, yes, I see," Angela said politely.

J.P. cringed. He was quite certain she didn't see at all, because she was from London, where there wouldn't be any weirdos, so how could she understand about weird phone calls? He was sorry he had tried to explain the J. Tate in the phone book.

"And, ah, my father lives in Des Moines, so of course we can't have his name in the New York directory," J.P. went on. "His name is Herbert," he added.

"Des Moines?" Angela said.

"That's a city. It's nowhere near New York. My parents are divorced."

"Oh," Angela said. "So are mine. I'm here with my father, but my mother is still in London. So my father's name—William— could be in the book, but of course we haven't been here long enough. So if you looked for Galsworthy, there might be some, but they wouldn't be me. Though of course there's no reason why you would look for Galsworthy, is there?"

She sounded a little nervous, J.P. realized.

"Well, I might," he said. "If I wanted to ask about a school assignment or something."

"Actually," Angela said, "that's why I rang you up. I thought we might arrange a place to meet to go over the map of London in the morning, before English class." She paused. "You do have a map of London, don't you, J.P.?"

"Of course I do." J.P. tried to make himself sound very slightly outraged at the question. "I wouldn't have raised my hand if I didn't."

"No, certainly not," Angela said apologetically. "Shall we meet just before school? Could you come a bit early?"

"I suppose so," J.P. replied. You name the time, he thought. Four A.M.? I could be there at four A.M. No prob.

"At the school library, then, about eight. That should give us time, shouldn't it?"

J.P. agreed, and they said goodbye. He returned the phone to the kitchen, ignored his mother's and sister's questioning looks, and went back to his math. Now, when he envisioned the Porsche speeding along the road to Monte Carlo, he envisioned himself in the driver's seat. He pictured the top down, and the wind blowing his hair. Beside him, gazing rapturously into his face, as he fearlessly maneuvered the sleek car down the dangerous, curving mountainous roads (steering with one gloved hand; the other arm was around her shoulders) was Angela Patricia Galsworthy.

4

This morning Angela had worn her hair differently, J.P. noticed, when he entered the school library and saw her sitting there waiting for him.

Usually J.P. paid no attention to hair. He paid no attention to his own, except to have it cut now and then, when his mother insisted; and he certainly paid no attention to girls' hair of any sort.

Yet this morning he noticed that Angela Galsworthy was wearing her hair differently. It was not flowing loosely across her shoulders as it had last week, and it was not tied into a thick, gleaming ponytail as it had been yesterday. Today it was folded into a smooth, shimmering knot at the top of her head, exposing her slender neck. And in front of her small pink ears, strands of the golden hair fell in tendrils.

Tendrils. J.P. actually thought that word. He cringed. He blushed and felt his face grow warm.

Angela was smiling at him. "Good morning," she said.

"Hi," J.P. muttered. His shoulders bumped the side of the door as he entered the library, and he tripped over the end of one shoelace. A book toppled from the pile of schoolbooks in his arms. When he knelt to retrieve it from the floor, his calculator fell from his shirt pocket.

On top of everything else, he sneezed. J.P. didn't have a cold, or any allergies that he was aware of. But he sneezed, and he knew that when he sneezed his face got all scrunched up and looked weird, right in full view of Angela Galsworthy. Probably, too, the sneeze left a highly visible drop of something repulsive on the end of his nose; he couldn't reach to wipe it because of the armload of books.

Red-faced, he stumbled and lurched to the library table where she waited. When he sank down, finally, to the chair across from her, its imitation leather seat made a noise that was half hiss, half squeak. Even the furniture was out to humiliate J.P. Tate.

But Angela Patricia Galsworthy only smiled and reached for the folded map that was on top of his stack of books.

>

"What a perfectly lovely map, J.P.," she said.

He cleared his throat and hoped that his voice wouldn't come out a squawk, as it sometimes did.

"Call me James," he told her.

Mrs. Hunt called J.P. aside as English class ended. He could see Angela linger in the doorway, as if she were waiting for him. Then some of the girls pulled her away and she followed them down the hall toward her next class.

"I want to commend you, J.P.," Mrs. Hunt said. "It was so helpful, having that map. I think the whole class has a much better sense of where the book is taking place, now."

"Yeah, well, it was really Angela who showed them. I've never been in London myself."

"I know. And I did thank Angela. But the reason I kept you here was to speak to you about something privately. I didn't want to embarrass you in front of the class."

J.P. looked at her uncomfortably. There was something massively unnerving about a teacher wanting to speak to you privately. He tried to remember if he had handed in all of his book reports.

"I've been noticing the past few days," Mrs. Hunt went on in a concerned voice, "that you seem to be walking a little unsteadily."

"Unsteadily," J.P. repeated.

Mrs. Hunt nodded. "I saw you bump into the doorframe when you entered the classroom this morning. And then you stumbled in the aisle as you went to your seat."

"Stumbled," J.P. said.

"Are you feeling all right?" his teacher asked.

How on earth could he answer that? How could he tell Mrs. Hunt, who was about a hundred and nine years old, that he felt fine, that he felt wonderful, that he was in love for the first time in his life? And that it was making him walk into doors, and trip over his own feet, and causing his hands to sweat and his ears to itch and his voice to croak and warble? Mrs. Hunt, he should say, my heart is soaring all the time, and I hear music playing, and when Angela Galsworthy smiles my pulse jumps to about three hundred and my nerves all tingle and the temperature of the back of my neck shoots up to about 140 degrees Fahrenheit, and—

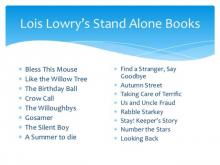

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver