- Home

- Lois Lowry

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver Page 4

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver Read online

Page 4

Stirrings. He had heard the word before. He remembered that there was a reference to the Stirrings in the Book of Rules, though he didn’t remember what it said. And now and then the Speaker mentioned it. ATTENTION. A REMINDER THAT STIRRINGS MUST BE REPORTED IN ORDER FOR TREATMENT TO TAKE PLACE.

He had always ignored that announcement because he didn’t understand it and it had never seemed to apply to him in any way. He ignored, as most citizens did, many of the commands and reminders read by the Speaker.

“Do I have to report it?” he asked his mother.

She laughed. “You did, in the dream-telling. That’s enough.”

“But what about the treatment? The Speaker says that treatment must take place.” Jonas felt miserable. Just when the Ceremony was about to happen, his Ceremony of Twelve, would he have to go away someplace for treatment? Just because of a stupid dream?

But his mother laughed again in a reassuring, affectionate way. “No, no,” she said. “It’s just the pills. You’re ready for the pills, that’s all. That’s the treatment for Stirrings.”

Jonas brightened. He knew about the pills. His parents both took them each morning. And some of his friends did, he knew. Once he had been heading off to school with Asher, both of them on their bikes, when Asher’s father had called from their dwelling doorway, “You forgot your pill, Asher!” Asher had groaned good-naturedly, turned his bike, and ridden back while Jonas waited.

It was the sort of thing one didn’t ask a friend about because it might have fallen into that uncomfortable category of “being different.” Asher took a pill each morning; Jonas did not. Always better, less rude, to talk about things that were the same.

Now he swallowed the small pill that his mother handed him.

“That’s all?” he asked.

“That’s all,” she replied, returning the bottle to the cupboard. “But you mustn’t forget. I’ll remind you for the first weeks, but then you must do it on your own. If you forget, the Stirrings will come back. The dreams of Stirrings will come back. Sometimes the dosage must be adjusted.”

“Asher takes them,” Jonas confided.

His mother nodded, unsurprised. “Many of your groupmates probably do. The males, at least. And they all will, soon. Females too.”

“How long will I have to take them?”

“Until you enter the House of the Old,” she explained. “All of your adult life. But it becomes routine; after a while you won’t even pay much attention to it.”

She looked at her watch. “If you leave right now, you won’t even be late for school. Hurry along.

“And thank you again, Jonas,” she added, as he went to the door, “for your dream.”

Pedaling rapidly down the path, Jonas felt oddly proud to have joined those who took the pills. For a moment, though, he remembered the dream again. The dream had felt pleasurable. Though the feelings were confused, he thought that he had liked the feelings that his mother had called Stirrings. He remembered that upon waking, he had wanted to feel the Stirrings again.

Then, in the same way that his own dwelling slipped away behind him as he rounded a corner on his bicycle, the dream slipped away from his thoughts. Very briefly, a little guiltily, he tried to grasp it back. But the feelings had disappeared. The Stirrings were gone.

6

“Lily, please hold still,” Mother said again.

Lily, standing in front of her, fidgeted impatiently. “I can tie them myself,” she complained. “I always have.”

“I know that,” Mother replied, straightening the hair ribbons on the little girl’s braids. “But I also know that they constantly come loose and more often than not, they’re dangling down your back by afternoon. Today, at least, we want them to be neatly tied and to stay neatly tied.”

“I don’t like hair ribbons. I’m glad I only have to wear them one more year,” Lily said irritably. “Next year I get my bicycle, too,” she added more cheerfully.

“There are good things each year,” Jonas reminded her. “This year you get to start your volunteer hours. And remember last year, when you became a Seven, you were so happy to get your front-buttoned jacket?”

The little girl nodded and looked down at herself, at the jacket with its row of large buttons that designated her as a Seven. Fours, Fives, and Sixes all wore jackets that fastened down the back so that they would have to help each other dress and would learn interdependence.

The front-buttoned jacket was the first sign of independence, the first very visible symbol of growing up. The bicycle, at Nine, would be the powerful emblem of moving gradually out into the community, away from the protective family unit.

Lily grinned and wriggled away from her mother. “And this year you get your Assignment,” she said to Jonas in an excited voice. “I hope you get Pilot. And that you take me flying!”

“Sure I will,” said Jonas. “And I’ll get a special little parachute that just fits you, and I’ll take you up to, oh, maybe twenty thousand feet, and open the door, and—”

“Jonas,” Mother warned.

“I was only joking,” Jonas groaned. “I don’t want Pilot, anyway. If I get Pilot I’ll put in an appeal.”

“Come on,” Mother said. She gave Lily’s ribbons a final tug. “Jonas? Are you ready? Did you take your pill? I want to get a good seat in the Auditorium.” She prodded Lily to the front door and Jonas followed.

It was a short ride to the Auditorium, Lily waving to her friends from her seat on the back of Mother’s bicycle. Jonas stowed his bicycle beside Mother’s and made his way through the throng to find his group.

The entire community attended the Ceremony each year. For the parents, it meant two days holiday from work; they sat together in the huge hall. Children sat with their groups until they went, one by one, to the stage.

Father, though, would not join Mother in the audience right away. For the earliest ceremony, the Naming, the Nurturers brought the newchildren to the stage. Jonas, from his place in the balcony with the Elevens, searched the Auditorium for a glimpse of Father. It wasn’t at all hard to spot the Nurturers’ section at the front; coming from it were the wails and howls of the newchildren who sat squirming on the Nurturers’ laps. At every other public ceremony, the audience was silent and attentive. But once a year, they all smiled indulgently at the commotion from the little ones waiting to receive their names and families.

Jonas finally caught his father’s eye and waved. Father grinned and waved back, then held up the hand of the newchild on his lap, making it wave, too.

It wasn’t Gabriel. Gabe was back at the Nurturing Center today, being cared for by the night crew. He had been given an unusual and special reprieve from the committee, and granted an additional year of nurturing before his Naming and Placement. Father had gone before the committee with a plea on behalf of Gabriel, who had not yet gained the weight appropriate to his days of life nor begun to sleep soundly enough at night to be placed with his family unit. Normally such a newchild would be labeled Inadequate and released from the community.

Instead, as a result of Father’s plea, Gabriel had been labeled Uncertain and given the additional year. He would continue to be nurtured at the Center and would spend his nights with Jonas’s family unit. Each family member, including Lily, had been required to sign a pledge that they would not become attached to this little temporary guest, and that they would relinquish him without protest or appeal when he was assigned to his own family unit at next year’s Ceremony.

At least, Jonas thought, after Gabriel was placed next year, they would still see him often because he would be part of the community. If he were released, they would not see him again. Ever. Those who were released—even as newchildren—were sent Elsewhere and never returned to the community.

Father had not had to release a single newchild this year, so Gabriel would have represented a real failure and sadness. Even Jonas, though he didn’t hover over the little one the way Lily and his father did, was glad that Gabe had not be

en released.

The first Ceremony began right on time, and Jonas watched as one after another each newchild was given a name and handed by the Nurturers to its new family unit. For some, it was a first child. But many came to the stage accompanied by another child beaming with pride to receive a little brother or sister, the way Jonas had when he was about to be a Five.

Asher poked Jonas’s arm. “Remember when we got Phillipa?” he asked in a loud whisper. Jonas nodded. It had only been last year. Asher’s parents had waited quite a long time before applying for a second child. Maybe, Jonas suspected, they had been so exhausted by Asher’s lively foolishness that they had needed a little time.

Two of their group, Fiona and another female named Thea, were missing temporarily, waiting with their parents to receive newchildren. But it was rare that there was such an age gap between children in a family unit.

When her family’s ceremony was completed, Fiona took the seat that had been saved for her in the row ahead of Asher and Jonas. She turned and whispered to them, “He’s cute. But I don’t like his name very much.” She made a face and giggled. Fiona’s new brother had been named Bruno. It wasn’t a great name, Jonas thought, like—well, like Gabriel, for example. But it was okay.

The audience applause, which was enthusiastic at each Naming, rose in an exuberant swell when one parental pair, glowing with pride, took a male newchild and heard him named Caleb.

This new Caleb was a replacement child. The couple had lost their first Caleb, a cheerful little Four. Loss of a child was very, very rare. The community was extraordinarily safe, each citizen watchful and protective of all children. But somehow the first little Caleb had wandered away unnoticed, and had fallen into the river. The entire community had performed the Ceremony of Loss together, murmuring the name Caleb throughout an entire day, less and less frequently, softer in volume, as the long and somber day went on, so that the little Four seemed to fade away gradually from everyone’s consciousness.

Now, at this special Naming, the community performed the brief Murmur-of-Replacement Ceremony, repeating the name for the first time since the loss: softly and slowly at first, then faster and with greater volume, as the couple stood on the stage with the newchild sleeping in the mother’s arms. It was as if the first Caleb were returning.

Another newchild was given the name Roberto, and Jonas remembered that Roberto the Old had been released only last week. But there was no Murmur-of-Replacement Ceremony for the new little Roberto. Release was not the same as Loss.

He sat politely through the ceremonies of Two and Three and Four, increasingly bored as he was each year. Then a break for midday meal—served outdoors—and back again to the seats, for the Fives, Sixes, Sevens, and finally, last of the first day’s ceremonies, the Eights.

Jonas watched and cheered as Lily marched proudly to the stage, became an Eight and received the identifying jacket that she would wear this year, this one with smaller buttons and, for the first time, pockets, indicating that she was mature enough now to keep track of her own small belongings. She stood solemnly listening to the speech of firm instructions on the responsibilities of Eight and doing volunteer hours for the first time. But Jonas could see that Lily, though she seemed attentive, was looking longingly at the row of gleaming bicycles, which would be presented tomorrow morning to the Nines.

Next year, Lily-billy, Jonas thought.

It was an exhausting day, and even Gabriel, retrieved in his basket from the Nurturing Center, slept soundly that night.

Finally it was the morning of the Ceremony of Twelve.

Now Father sat beside Mother in the audience. Jonas could see them applauding dutifully as the Nines, one by one, wheeled their new bicycles, each with its gleaming nametag attached to the back, from the stage. He knew that his parents cringed a little, as he did, when Fritz, who lived in the dwelling next door to theirs, received his bike and almost immediately bumped into the podium with it. Fritz was a very awkward child who had been summoned for chastisement again and again. His transgressions were small ones, always: shoes on the wrong feet, schoolwork misplaced, failure to study adequately for a quiz. But each such error reflected negatively on his parents’ guidance and infringed on the community’s sense of order and success. Jonas and his family had not been looking forward to Fritz’s bicycle, which they realized would probably too often be dropped on the front walk instead of wheeled neatly into its port.

Finally the Nines were all resettled in their seats, each having wheeled a bicycle outside where it would be waiting for its owner at the end of the day. Everyone always chuckled and made small jokes when the Nines rode home for the first time. “Want me to show you how to ride?” older friends would call. “I know you’ve never been on a bike before!” But invariably the grinning Nines, who in technical violation of the rule had been practicing secretly for weeks, would mount and ride off in perfect balance, training wheels never touching the ground.

Then the Tens. Jonas never found the Ceremony of Ten particularly interesting—only time-consuming, as each child’s hair was snipped neatly into its distinguishing cut: females lost their braids at Ten, and males, too, relinquished their long childish hair and took on the more manly short style which exposed their ears.

Laborers moved quickly to the stage with brooms and swept away the mounds of discarded hair. Jonas could see the parents of the new Tens stir and murmur, and he knew that this evening, in many dwellings, they would be snipping and straightening the hastily done haircuts, trimming them into a neater line.

Elevens. It seemed a short time ago that Jonas had undergone the Ceremony of Eleven, but he remembered that it was not one of the more interesting ones. By Eleven, one was only waiting to be Twelve. It was simply a marking of time with no meaningful changes. There was new clothing: different undergarments for the females, whose bodies were beginning to change; and longer trousers for the males, with a specially shaped pocket for the small calculator that they would use this year in school; but those were simply presented in wrapped packages without an accompanying speech.

Break for midday meal. Jonas realized he was hungry. He and his groupmates congregated by the tables in front of the Auditorium and took their packaged food. Yesterday there had been merriment at lunch, a lot of teasing and energy. But today the group stood anxiously, separate from the other children. Jonas watched the new Nines gravitate toward their waiting bicycles, each one admiring his or her nametag. He saw the Tens stroking their new shortened hair, the females shaking their heads to feel the unaccustomed lightness without the heavy braids they had worn so long.

“I heard about a guy who was absolutely certain he was going to be assigned Engineer,” Asher muttered as they ate, “and instead they gave him Sanitation Laborer. He went out the next day, jumped into the river, swam across, and joined the next community he came to. Nobody ever saw him again.”

Jonas laughed. “Somebody made that story up, Ash,” he said. “My father said he heard that story when he was a Twelve.”

But Asher wasn’t reassured. He was eyeing the river where it was visible behind the Auditorium. “I can’t even swim very well,” he said. “My swimming instructor said that I don’t have the right boyishness or something.”

“Buoyancy,” Jonas corrected him.

“Whatever. I don’t have it. I sink.”

“Anyway,” Jonas pointed out, “have you ever once known of anyone—I mean really known for sure, Asher, not just heard a story about it—who joined another community?”

“No,” Asher admitted reluctantly. “But you can. It says so in the rules. If you don’t fit in, you can apply for Elsewhere and be released. My mother says that once, about ten years ago, someone applied and was gone the next day.” Then he chuckled. “She told me that because I was driving her crazy. She Threatened to apply for Elsewhere.”

“She was joking.”

“I know. But it was true, what she said, that someone did that once. She said that it was really true. Here

today and gone tomorrow. Never seen again. Not even a Ceremony of Release.”

Jonas shrugged. It didn’t worry him. How could someone not fit in? The community was so meticulously ordered, the choices so carefully made.

Even the Matching of Spouses was given such weighty consideration that sometimes an adult who applied to receive a spouse waited months or even years before a Match was approved and announced. All of the factors—disposition, energy level, intelligence, and interests—had to correspond and to interact perfectly. Jonas’s mother, for example, had higher intelligence than his father; but his father had a calmer disposition. They balanced each other. Their Match, which like all Matches had been monitored by the Committee of Elders for three years before they could apply for children, had always been a successful one.

Like the Matching of Spouses and the Naming and Placement of newchildren, the Assignments were scrupulously thought through by the Committee of Elders.

He was certain that his Assignment, whatever it was to be, and Asher’s too, would be the right one for them. He only wished that the midday break would conclude, that the audience would reenter the Auditorium, and the suspense would end.

As if in answer to his unspoken wish, the signal came and the crowd began to move toward the doors.

7

Now Jonas’s group had taken a new place in the Auditorium, trading with the new Elevens, so that they sat in the very front, immediately before the stage.

They were arranged by their original numbers, the numbers they had been given at birth. The numbers were rarely used after the Naming. But each child knew his number, of course. Sometimes parents used them in irritation at a child’s misbehavior, indicating that mischief made one unworthy of a name. Jonas always chuckled when he heard a parent, exasperated, call sharply to a whining toddler, “That’s enough, Twenty-three!”

Jonas was Nineteen. He had been the nineteenth newchild born his year. It had meant that at his Naming, he had been already standing and bright-eyed, soon to walk and talk. It had given him a slight advantage the first year or two, a little more maturity than many of his groupmates who had been born in the later months of that year. But it evened out, as it always did, by Three.

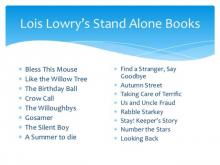

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver