- Home

- Lois Lowry

Stay! Page 4

Stay! Read online

Page 4

When I had lost my mother and siblings so long before, I had felt fear and frustration but at the same time a sense of independence and adventure. Now I was older. Now I knew I could survive alone. But I had a more adult understanding of the value of companionship and what I was losing as I lay there beside my friend and felt him slip away from me.

I tried again to write a poem, an ode to Jack. Only one word kept coming to me. Why? I said it to myself over and over again, searching for the rhyme that would go with it and turn it into a proper elegy.

But only one word surfaced, and that was the word that concluded what would be my shortest, and saddest, poem.

Goodbye.

6

AND SO I WAS ALONE AGAIN. A pup no longer, but still awash with the yearnings of youth.

I could have curled beside Jack’s body, mourning, and wasted away beside him in that grim setting. I have heard of dogs who do that out of loyalty, and are much admired for their sacrifice; they have statues and monuments erected in their honor. But such statues and monuments are always posthumous. I knew it was not what Jack would have wished for me.

“Lucky you are, and lucky you’ll be!” Jack had said to me often, in better days when his spirits were high and his jug by his side.

Lucky I am! Lucky I’ll be!

I wonder what’s in store up ahead!

Quickly, feeling foolish, I corrected the obvious error in the poem. In store for me, I amended.

Poetry is a difficult art, I thought as I neatened the area where Jack still lay. It was the least I could do for him, since I had decided against wasting away in his honor.

I rubbed my head affectionately against his lifeless fingers and whimpered a goodbye, adding why to make it into a variation on the elegy I had composed only a few hours before. Then I turned and left the hollow under the bridge, giving a final and very ferocious growl toward the sewer pipe, in hopes of keeping the rats unnerved. As I walked away from what had been my home during almost all of my formative first year, I held my head high in homage to Jack and all that he had taught me about life, adversity, and how to obtain food.

Upright, my tail! Forward, my feet!

The next line had not yet come to me, though I was considering fleet as an appropriate rhyme for a leavetaking, when suddenly I spotted something that caught my attention and wrote itself into the poem:

I see a child across the street!

It was true. In this most unsavory part of the city, beside a graffiti-covered board fence, a young boy wearing an odd hat stood alone, his hands in his pockets, a captivating smile on his face. He was clearly in need of protection, though his attitude was self-confident. I suspected that he did not know what danger might come to him if he loitered here. Glancing quickly both ways, alert to the vehicles my mother had repeatedly described as my greatest enemies, and as ever on the lookout for Scar, who might be lurking almost anywhere, I bounded across the street to the boys side.

Panting, I looked up at him, expecting a pat of welcome on my head. Humans always reach for the head, for some reason; it is actually the spot behind each ear that we dogs most prefer to have scratched. But we tolerate the head pat until we can maneuver ourselves into a position where the human understands the need. I planned to let the boy pat my head; then I would rub myself against his legs; then he would reach down and I would tilt myself into a position so that his hand would encounter the right place. It wouldn’t take long to train him. Jack had learned quickly, and this human was much younger and therefore even more educable.

To my amazement, he did not pat my head at all. He kicked me.

It wasn’t a painful kick, because he was wearing sneakers that were much too large and so the toes of them were empty. In truth, it was more of a foot-nudge. But it was a surprise, and a disappointment. It was contrary to every lesson my mother had taught me about children.

“Get lost!” he said.

And that was a surprise, too. According to my education, the first words a child usually says, upon encountering a new and appealing dog (I was assuming, of course, myself to be appealing. In my new maturity, I felt that my tail, in particular, had developed a certain plumelike quality; and as for behavior, I had certainly been on my best, though I must say the boy had not), are “Can I keep him?”

So “Get lost” came as a surprise. In addition, since I already felt myself to be somewhat lost, I did not see how I could possibly “get” more so. I stared at the boy curiously. In addition to the very large shoes and the hat that looked like an unsuccessful cupcake, he was wearing enormously baggy trousers and a bright-colored shirt with writing on it.

“Beat it!” he whispered to me, appearing more frustrated than ill-tempered. “You’re ruining my shot!”

Shot? He had no gun. He didn’t even look like someone who wanted to have a gun. He was a boy. A kid.

I hesitated, looking around to see what was going on.

Farther down the street I saw a number of people grouped around a large camera. A tall woman with a notebook was writing things down as if they were important. A man was adjusting some tall lights with pale umbrellas behind them.

“What’s with the dog?” the woman asked, looking up from her notebook. “Whose is he? Is that your dog, Willy?”

“Moi?” A thin man wearing a denim jacket asked. “No way. I’m a cat person.”

Whose is he was a phrase that raised my hackles. Why is it that humans feel dogs belong to them? How can that be? Jack never felt that way, or treated me like property. We had chosen each other, Jack and I.

If I were ready to choose another human—and I was not—it would not be this thin man who had already announced his preference for cats, a dubious species at best.

Even as I was thinking about it, the man named Willy jogged toward me, carrying a leather case. “I’m just going to touch up your hair,” he said cheerfully, and took a comb from the case. I winced. I didn’t want my fur tampered with, and especially not by a man whose clearly professed commitment was to cats.

But he was talking, it appeared, to the boy. He removed the hat, combed and arranged the boy’s hair so that it appeared windblown and casual, and then replaced the unattractive hat so that the freshly groomed hair was hidden.

“I can’t get the dog to go away,” the boy complained to him.

“What about the dog?” the hair person called to the camera people. “I don’t want to be the one to drag him away. He looks like a biter to me!”

The dog: a phrase I loathe. A biter indeed. I wished Jack were alive. Jack would tell them where to go. There had been times in our past, Jack’s and mine, when people had been apprehensive about “the dog” and Jack had been very firm with them, explaining that the dog had feelings and intelligence, that the dog had more integrity than most humans, and that, most important, the dog had a name and should be addressed accordingly. Sometimes people would drop money into Jack’s outstretched hand and hurry away quickly, just to flee the lecture about mans best friend.

“I love the dog,” the woman with the notebook called. “Keep the dog. The dog works.”

I wasn’t entirely certain what she meant by that. Of course I worked. I worked at staying alive, finding food, guarding against rats, and tending Jack when things turned bad.

“I’d like the dog’s hair a little more disheveled, Willy,” she called. “Think you can do that for me?”

Willy was the man with the comb, the one who had called me a biter. He glanced down at me now, and I raised my lip a little. I murmured a warning. It wasn’t a growl, really, but Willy didn’t know that.

“I only do humans,” Willy announced. “Absolutely no canines. For canines you get a groomer.”

I lay down as they argued. By now I wished I had simply moved on and left these humans to their unfathomable tasks. But I was beginning to sense that there could be some rewards in this for me.

“All right, places! Take your places!” The man behind the camera called, after the arguments seemed to die

down a bit. “Let’s get this done while we still have the light!”

“Andrew, hit that pose again!” he called, and the boy went back to the stance I had seen at first, the grinning, self-confident pose that had attracted me from across the street.

I stood back up, alert now. My ears went taut. My tail was a fringed banner behind me.

Beside the boy I stand! I pose!

Erect, my ears! Shine, my nose!

“Great!” the photographer called. “Good dog! Stay!”

So I stayed. It was a new beginning for me.

7

WHEN THEY FINALLY FINISHED taking photographs, everyone seemed to disperse quickly. Willy, the man with the comb, snapped his makeup case closed and got into a waiting car. The woman with the notebook snapped it shut and got into the car with Willy.

Several other, minor people hailed passing cabs and disappeared into the traffic.

The boy, the one I had thought so briefly would become the child I had wanted, snapped his smile off as soon as the camera closed down. His face became a frown, and he walked briskly off to a car with two adults who seemed to be his attendants. He never looked back at me. So much for my “boy and his dog” fantasy.

I had been told “Stay” and so I stayed, partly out of curiosity and partly because I did not know what else to do.

Then only the photographer was left. It had taken him a while to fold his complicated lights, replace his equipment in cases, and load everything into a Jeep that was parked nearby. I was impressed by his meticulousness.

Finally he looked around to see if he had forgotten anything. He picked up an empty film canister and tossed it into a trash can. Then his eyes fell on me.

I was still in my “stay” position: alert, waiting, head high.

The photographer smiled. He came over, squatted beside me, and scratched behind my ear, completely bypassing the uncomfortable head pats that dogs ordinarily have to endure on short acquaintance. Clearly he was a man accustomed to dogs. My heart beat faster.

“What’s up, pal?” he asked. I noted the name change. So I was Lucky no longer. It required a quick adjustment in my thinking.

Lucky I was, now I’ll be Pal!

I was still pondering the second line (possibly something referring to morale, I thought) when he rose, stretched, grinned, and said the word that I most longed to hear.

“Come,” the photographer said.

I followed him eagerly to the Jeep and hopped onto the back seat when he opened the door. I sat politely, avoiding making pawmarks on the seat, and tried not to lean too close to the window, though I was wild with curiosity and excitement. I had never been in a vehicle before. But there is some primal inborn awareness in dogs, and I knew instinctively that it would not serve my future well if today I got drool and dog breath on the windows.

If he learned to love me now, I could slobber all over soon. The combination of timing, self-restraint, and discretion is the art that separates the successful dog from those foolish canines who find themselves at the ends of leashes and on the floor of school gyms having obedience lessons.

Watching carefully through the windows of the Jeep, I could see that we were making our way through the same streets that I had walked with Jack. I saw the same corner, in fact, where I had met Jack while fleeing the scar-faced dog who had beaten me out for the McDonalds breakfast and become my mortal enemy. I felt as if there should be some memorial there, a marker for Jack, whose life had been lived on that corner; but it was simply an unacknowledged place with a trash can, a mailbox, and a lamppost: nothing physical to mark a spot where the groundstone of a relationship had been laid.

As we slowed for a light, I saw suddenly the carved wooden door, with the menu attached to its window, that was the familiar entrance to Toujours Cuisine. I realized that we were passing the alley where I had been born. Eagerly I rose to the full length of my legs, unsteady on the slick surface of the car seat. I leaned toward the window, forgetting the dangers of spit on the pane, and found myself whimpering.

The photographer slowed the Jeep and turned to me with a concerned look. “You okay?” he asked. “Not carsick?”

I gave him what I thought was an imploring look. If only, the look said, if only we could stop for a moment? Please? And perhaps I might find my beloved mother still on these familiar sidewalks. Or my siblings—well, really only the one, my favorite, my sister, little Wispy?

He smiled at me. His smile was warm, intelligent, and compassionate. But he had not understood my look, or my yearning; when the light changed, he propelled the Jeep ahead. “Almost home, pal,” he said consolingly.

So I lay back down on the seat and composed a mournful poem—I believe it could rightly be called an elegy—in my head. For the first time, the rhyme came easily, naturally. For the first time I felt what true poets must feel when the words fall into place.

Be brave, my heart; be still, be calm!

Adieu to Jack. To Wisp. To Mom…

My life seemed an unending series of leavetakings. Unaware of my grief and loneliness, the photographer drove around a corner, and behind us the familiar neighborhood slid away with whatever it still contained of my past.

To my surprise (and, I confess, to my chagrin, since I had just composed such a complex ballad of goodbye), we stopped in front of a brownstone building that was no more than two blocks from my old haunts.

“This is it, pal,” the photographer said as he began to unload his equipment from the Jeep. “Your new home, if you feel like it. I don’t have a leash, and you’re free to take off if you want. Or you can come on in and make yourself comfortable. You look hungry. Could you handle some leftover pasta? If you decide to stay, I’ll buy some dogfood in the morning.”

I might have been tempted to trot off around the corner, back to the old neighborhood. But like Jack, he had announced himself as a leash-free human. There would be no choke collar, no rhinestone-studded lead such as I had seen on a passing Bedlington terrier (the sight had made me avert my eyes in embarrassment). It would just be me—once Lucky, now Pal—unrestrained, with what looked like a warm and pleasant roof over my head.

And pasta. To tell the truth, it was the mention of pasta that did it.

Legs, be steady! Mouth, get ready!

I trotted behind the photographer up the stairs. From hunger and anticipation I simply dismissed the high art of poetry from my mind and turned to primitive rhyming chant instead. I murmured it under my breath up three flights of stairs:

spaghetti spaghetti spaghetti spaghetti.

Quickly and happily I settled into my new digs. There was a bit of a power struggle over sleeping places until finally, grudgingly, I agreed to sleep on a blanket folded in the corner. In return, the photographer agreed to refrain from kibbles and nourish me with pasta whenever possible.

These decisions were reached, of course, without conversation. Life would be easier for dogs if humans could comprehend our speech as we do theirs. Instead, we have to resort to pantomime and subterfuge.

I won’t even bother to describe the on-or-off-the-bed struggle we endured before we came to an understanding. The ultimate compromise was this: during the night, he slept on the bed and I slept on the floor. During the day, if he was at home, I slept on the floor. If he was out of the apartment or closed away in his darkroom, as he often was, I curled up on the bed. When he returned, I got down with a great show of languid boredom, leaving pawprints which he pretended not to notice.

We postponed dealing with the issue of the couch.

It was early afternoon on the third day. “Pal?” The photographer spoke gleefully to me as he emerged from the darkroom in his apartment. “You’re not gonna believe this!”

He was carrying a dripping wet photograph; while I watched, he took it over near the window and examined it in the bright light there. He whistled. Startled by the sound, I jumped a bit from the folded blanket in the corner that had been designated my space. Ordinarily when a human whistles, it means

that a dog is being summoned.

But this wasn’t a shrill, dog-calling sound. It was a low, extended whistle of admiration. Self-admiration, actually, since he was whistling at one of his own photographs.

I could forgive him a little self-congratulation, since I am prone to it myself. I understand the feeling of ecstasy and pride when one has accomplished something. For me it is most often a particularly fine pose, perhaps on a windy day when my fur ripples and my glorious tail is extended with its ornamental fringe parted in waves and I know that I am a magnificent sight. If I could whistle then, I would. But a dog’s mouth is not configured for whistles, and so most often I simply emit a low groan of pleasure, unintelligible to humans.

“Look!” he said excitedly, and knelt beside me with the wet photograph in his hands. On his part, it was simply a gesture, since he did not truly expect me to look, or to admire his work. Humans believe (wrongly) that a dog’s thoughts extend no further than the basic needs of food, shelter, and reproduction.

If they only knew what complex creatures we really are, and how deeply aesthetic our tastes!

But I was touched by his gesture, and in fact, when he thought I was simply nuzzling his hand in search of tidbits, I was actually studying the photograph very carefully.

It was one that he had taken on the day of our meeting, only three days before. I stood beside the boy, who was grinning in that supercilious way, with his hands in his pockets, displaying his baggy trousers, enormous sneakers, and macaroon-like cap, pretending that he was in love with his clothes.

My look was one of disdain. Disdain for the boy, for his clothes, for his smile, for the entire surrounding world. My lip was ever so slightly curled, my eyes half closed in boredom, my ears limp with ennui.

It was, I have to admit, a marvelously sophisticated look, one that said attitude. I admired it. I admired myself for creating it. Unconsciously, sitting there on my frayed blanket, the photo in front of me, I created it again on the spot, lowering my eyelids, raising my lip a micromillimeter, turning my neck an infinitesimal bit to the left.

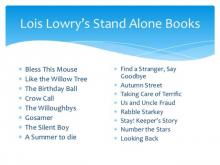

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver