- Home

- Lois Lowry

Anastasia's Chosen Career Page 7

Anastasia's Chosen Career Read online

Page 7

"Of course! Terrific!" Barbara Page said. "I love having company."

"I'm afraid she won't be able to buy a book," Anastasia explained apologetically. "She's studying to become a model so that she can earn the money to go to college, so—

"Hey," Barbara Page interrupted, laughing. "I said I love having company. I didn't mean I love having customers."

***

"Whaddaya mean, she had an autographing party for your father? Is your father a rock star or something?"

Anastasia shook her head. They were walking across the Common toward Beacon Hill. "He's just a college professor. But he writes poetry, too."

"Real poetry? In books? Not just funny poems for uncles' birthday parties and stuff?"

Anastasia nodded. "No. Of course he does that, too. But he writes real poetry. In books."

"Jeezum," said Henry. "Real books. Do they have his name on them?"

"Sure. Right across the front. And they have his picture on the back."

Henry looked awed. "So he's famous," she said.

Anastasia felt embarrassed. She didn't think of her father as famous. Still, every now and then, they wrote about him in the New York Times. Once they had called him "Master of the Contemporary Image," whatever that meant. And strangers wrote fan letters to him, asking for his autograph. So she guessed he was famous, at least a little.

"Yeah," she admitted. "I guess so."

"I never once in my whole entire life knew the daughter of a famous person before," Henry said.

Anastasia tried to think of a response. "I never knew a truly beautiful person before," she said, finally. "In fact, when I first knew you, just two days ago, I didn't even recognize that you were beautiful. And now look. Do you realize, Henry, that right now, right this very minute, as we walk through the Common, men are staring at you because you're so beautiful? Grown men?"

"Yeah, I know. It's weird. Last night, when I was going home on the T, men stared at me. Women even stared at me. That never happened to me before."

"Is it scary?"

Henry shook her head. "No. Not if they just stare. But if they say anything, they die."

And Barbara Page stared, too, when they entered the bookstore. She stared at both of them as Anastasia introduced her to Henry.

"Anastasia," she said, "your haircut is fabulous, and I want you to give me the name of the person who cut it, because I want to make an appointment.

"And, Henry," she went on, "you are gorgeous. There's no other word for it."

"Yes, there is," Anastasia told her in surprise. "You of all people—a person who owns a bookstore—ought to know that. There are lots of other words for it. Dazzling. Spectacular. Magnificent. Just plain beautiful, for pete's sake."

"Okay, okay." Barbara Page laughed. "You're right."

"Wanta see what we learned at modeling school this morning?" Henry asked.

"Sure. Show me."

Henry dropped her jacket on a bench in a corner of the bookstore. She posed, standing straight; then she took a deep breath and walked across the floor to the opposite wall of bookcases. Her chin was high, her shoulders taut, and her long legs moved with a kind of grace that Anastasia had never seen on anyone before. Instead of hanging at her sides like every other pair of arms in the whole world, Henry Peabody's arms moved with a fluid ease. She turned, smiled slowly, and strode back toward them with the same gliding movement.

Then she grinned. "Whaddaya think?" Henry asked. "Panther, or what?"

"Panther," Anastasia said. "For sure."

Aunt Vera had directed them, in class, to imagine themselves as animals. After they had finished goofing off and acting stupid because they were all so embarrassed, they had tried.

Bambie had chosen a mountain goat. Mountain goats, Bambie explained, would have a determined, sure-footed walk. Then she mountain-goated across the room with her red curls bouncing. Ho hum.

Helen Margaret had hung her head and said softly, "I'll try to be a deer, I guess." She walked timidly across the room, darting looks at Aunt Vera to see if she was doing it right. She did resemble a deer, Anastasia thought, remembering a deer she had seen once at the edge of a meadow; Helen Margaret had the same fearful, shy look, the same careful steps, the same vigilance.

Robert went next. "Cheetah," he announced, which was a joke before he even started. There was no way that Robert Giannini could look like a cheetah. He clumped across the room; Aunt Vera smiled a polite but pained smile, and Henry muttered under her breath, "Make that hippo."

"Ah, well, I guess I'll try lioness," Anastasia said when her turn came. She walked across the room, imagining herself stalking game on the African veldt. But she tripped on an untied shoelace and started to laugh. "I meant giraffe," she said.

Henry had simply said "Panther," and then she had panthered herself across the room so magnificently that everyone—even Bambie—burst into applause.

Now she had done it again in the bookstore. She became a panther somehow.

"This afternoon," Anastasia told Barbara Page, "we practice speaking. I think I can do that better than walking."

"If Bambie Browne does her Juliet death scene again," Henry said, and she imitated Bambie, "'to whose foul mouth no healthsome air breathes in,' well, you might just hear a foul mouth make a comment. And it'll be mine."

Barbara Page made a tsk-tsking sound, but Anastasia could see she was laughing silently.

Over a lunch of egg salad sandwiches, Anastasia said, "You know, the modeling course is actually kind of fun. The haircuts and make-up day was a whole lot of fun. And this morning wasn't bad, even if I did turn out to be a giraffe."

"You should try panther," Henry commented, shaking some pepper onto her egg salad.

Anastasia made a face. "I don't think I'm pantherlike, Henry. I'm too klutzy. Anyway, I like giraffes."

"I like giraffes, too," Barbara Page said. "My husband and I went on safari in Africa last year, and we saw a lot of giraffes."

Henry's eyes widened. "Safari?" she said. "Africa?"

"Who ran the bookstore while you were away?" Anastasia asked.

Barbara looked a little embarrassed. "I just closed it down," she said. "I probably should have hired someone to come in and take charge. But I didn't trust anybody to know how to handle all the senior citizens and the little kids and all my customers that I know so well. So when I go on vacation, I just lock up the shop."

"You need to train an assistant," Anastasia suggested.

"Maybe."

"A young assistant," Anastasia said.

"I suppose so."

"Someone like me," Anastasia said.

Barbara smiled. "That's a good thought," she said. "Maybe next summer we can discuss a part-time job for you. And then eventually, when you're older, I could leave you in charge, and my husband and I could go to Africa again. I'd love to go back.

"As a matter of fact," she said suddenly, "when you came in here, Henry, you reminded me of something—or someone—and I couldn't put my finger on what it was. But I just realized. Look." She walked over to the section marked travel and reached for a large book. She leafed through its pages, found what she wanted, and turned to show the photograph to Henry and Anastasia.

"Jeezum," Henry said softly. "My haircut." She took the book from Barbara Page and sat down.

Anastasia peered over Henry's shoulder and looked at the portrait of the Masai woman. She was wrapped in a red blanket and had large, beaded necklaces around her throat and rings of beads dangling from her ears. Her head was shaved down to a thin layer of hair, the same as Henry's, and she had Henry's high cheekbones, slender neck, and large dark eyes.

"I saw a lot of women who looked just like her—and you—in Kenya and Tanzania," Barbara Page said. "They were all very beautiful."

Henry closed the book slowly and laid it on the desk. She looked worried. "You don't think they'll all come over here and go to modeling school?" she asked. "I don't think I can deal with all that competition."

Barbara Page laughed. "I don't think so," she said.

"Can I look at the children's books?" Henry asked. "I got two little nephews who like books."

"Sure. Go through the ones on the little table, and if you find one you want, you can have it. The nursery school comes in here for story hour, and the kids have dirty hands sometimes. So those books have some smears, and I can't sell them."

While Henry was leafing through the children's books on the table, Anastasia sat down beside Barbara Page's desk and spoke softly. "I told you I wanted to buy a book," she began.

Barbara Page laughed. "Don't be silly. Take one of those kids' books home for your brother—no charge. I'm not going to take your money."

"No, wait," Anastasia whispered. "I really want to. But I didn't know which book I wanted. And now I do. I want to buy that one." She indicated the book on the desk. "I want to buy it for Henry, so she can look again and again at how beautiful the Masai woman is."

Barbara Page smiled. "I'm sorry, Anastasia. But it's not for sale. It's already spoken for."

"Rats."

The telephone rang. "Could you answer that, Anastasia, and practice being a bookstore owner? Get it in the front room. I have some stuff to tend to in here."

Anastasia nodded and went to the front of the bookstore where another telephone was on the wall. "Pages, good afternoon," she said, remembering how Barbara Page always answered the phone. Henry, sitting at the children's table, looked over at her and grinned.

"Barbara?" a woman's voice asked.

"No," Anastasia answered, "Mrs. Page is busy at the moment. This, is her assistant. May I help you?" She crossed her fingers, hoping the woman had a question she would be able to answer.

"Well, I'm looking for a gift for a friend. Could you recommend something? Nonfiction, I think."

Anastasia glanced quickly at the shelves. She saw cookbooks, gardening books, biographies, travel books, photography books.

"Well, ah, what are your friend's interests?" she asked.

"She's quite literary," the woman responded. "She's the librarian at a boys' boarding school."

Suddenly Anastasia's eyes fastened on a particular section of the shelves.

"In that case," she said into the telephone, "she would appreciate an autographed edition. And we just happen to have here an autographed copy of the latest volume of Myron Krupnik's poetry."

"Myron Krupnik? Have I heard of him?"

"I should hope so," Anastasia said. "The New York Times called him 'Master of the Contemporary Image.'"

"Goodness. Well, I think she would like that. You say it's autographed?"

"It certainly is. He has terrible handwriting, but lots of famous people have terrible handwriting. I know someone who got Bruce Springsteen's autograph once, and Bruce Springsteen had terri—"

"Yes, well, could you gift wrap that and mail it for me? I'll give you the address and you can charge it to my account."

Anastasia copied down the information carefully. Then she took it triumphantly to the back room, where Barbara Page was still at her desk. "I sold a book!" she said.

"No kidding!" Barbara Page looked delighted.

"My own father's book! She wants you to mail it to her friend. Here's the address."

"Anastasia, I think you have a great future as a bookstore owner. Thank you. Now, here—it's almost one o'clock. You guys have to go back and practice talking. Not that you seem to have any trouble with it, either one of you." She handed Anastasia and Henry each a paper bag with pages printed on the side in wide blue letters.

"What's this?" Anastasia asked.

"A present for each of you. And a few smeary books for your little brothers and nephews."

She walked them to the door with an arm around each of them. "Come back and see me again, okay?"

"Okay, and thank you," Henry and Anastasia said.

Outside, walking back through the Common, they looked inside their shopping bags. Anastasia found a book about trucks for Sam and a book for herself which contained beautiful color photographs of animals. Inside the front cover, Barbara Page had written, "For my friend and future bookstore owner, Anastasia Krupnik. Giraffes are my very favorite. With love from Barbara Page."

Henry pulled out the two picture books she had chosen for her nephews and the book that contained the picture of the Masai woman. Inside, Barbara Page had written, "For Henrietta Peabody, who comes from a long tradition of great beauty."

Henry held it out, looking stricken.

"Anastasia," she said, "I saw the price on this book. It was thirty-five dollars!"

"Well," Anastasia said, thinking it over, "she wanted you to have it. Like my father said, she's a terrific person. And she can afford it. But boy, she sure is a terrible bookstore owner, though.

"Oh, no!" she added, remembering something. "Oh, rats! I forgot to do the interview again!"

But Henry wasn't listening. She was turning the pages of the book slowly. She found the Masai woman, stared at her silently as they walked, and then turned back to the inscription again. "I sure am glad," she said finally, "that she wrote my real name: Henrietta."

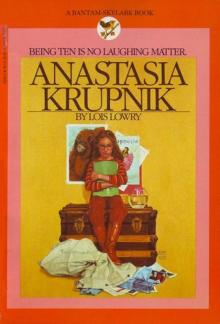

Anastasia Krupnik

My Chosen Career

It really is not all that difficult being a bookstore owner. If someone calls up and asks you to recommend a book, it is really pretty easy to convince them to buy something, like maybe a book by a moderately successful poet,* just by speaking pleasantly to them about it. Of course, if they come into the store, you have to look them in the eye at the same time.

One of the problems with being a bookstore owner, if you are a terrifically nice person, is that you are tempted to give stuff away.

If you sell a book by a moderately successful poet* for $12.95, and on the same day give away a book that costs $35, you will be a terrible failure as a bookstore owner even though you would still be a terrifically nice person.

You could solve this by selling the $35 book and giving away the $12.95 book. That way, you would still be a terrifically nice person, and you could also be a moderately successful bookstore owner.

10

"I've never been in Dorchester before," Anastasia said to Henry as they sat side by side on the rattling subway. "Imagine that. All my life I've lived in Boston but I've never been in that part of Boston before."

"Well, shoot, that's no surprise," Henry said. "All my life I've lived in Boston and I've never been to the suburbs where you live, either."

"Maybe you could come to my house sometime. You'd like my family."

"What're they like? I know your dad is famous and all. But what're your parents really like?"

"Well, my dad has a really neat beard. It's the same color as my hair. And he tells terrible jokes, and he watches sports on TV. When he's working on a book of poetry he shuts himself up in the study and groans about how he should have chosen another career."

"That's so cool," said Henry. "In school, I always like when we study poems. And now that we learned about walking and talking and stuff, I bet I'll do really good when we have to recite. Shoot, maybe I'll do gestures, like Miss Cranberry Bog."

They both collapsed in giggles, and an elderly lady sitting nearby stared at them. No men were staring at Henry, but that was because she had her hat on. If she took her hat off, Anastasia knew, she would change to beautiful in about the same way that Clark Kent changed to Superman. Then men would stare at her.

"And my mom's an artist," Anastasia went on. "She works at home, so she can take care of my little brother at the same time. She illustrates books."

"My mom's a waitress. That's the hardest job in the whole world. You should see how her feet swell up. She has to soak them when she comes home. Boy, I'm never going to be a waitress."

"Well, of course not, Henry. You're going to be a model."

"Yeah." Suddenly Henry sat up very straight and removed her hat. Two men sitting together on the opposite side of the train stopped talking, nudged each other, and stared.

"Just testing,"

Henry remarked in a whisper to Anastasia, and grinned. She put her hat back on and slouched down again.

"What does your dad do?" Anastasia asked.

"Policeman."

"No kidding! Does he have a gun?"

"Whaddaya mean does he have a gun? Of course he has a gun. You think he wants to be the only cop in Boston with no gun?"

"Did he ever shoot anyone?" Anastasia asked in awe.

Henry shook her head. "Nope. Never once. Once he had to aim it at somebody, though. It gave him nightmares afterward."

Anastasia shuddered. Never in her whole life, she thought, had she known someone whose father had once aimed a gun at someone.

"We get off here," Henry announced as the train slowed and stopped. Anastasia followed her through the subway station and out into the street.

The Peabodys' house, two blocks away, was gray, a little in need of new paint, with a big front porch. Inside, it smelled of something delicious cooking. And it was noisy. Two small children ran giggling through the front hall as the girls were taking off their jackets and hats. Henry grabbed one of them by the shoulders, and the other stopped, stood still, and looked up shyly at Anastasia.

"These are my sister's kids," Henry explained. "It's my mom's day off, so she's babysitting. This evil one's Jason." She wiggled the arm of the one she was restraining, and the little boy grinned. "And that one there, that's John Peter. Say hi, you guys."

John Peter opened his mouth, his eyes wide, and whispered, "Hi." Jason squirmed loose from Henry's grasp and stuck out his tongue. Then they both ran off, laughing.

"Henrietta? Is that you?" a voice called. 102

Henry hung up her jacket and called, "Yes, Mom. I have Anastasia with me. We'll be right in."

"You walk in here normal, Henrietta," her mother called. "None of that panther stuff."

Anastasia followed Henry into the warm kitchen, where the two little boys were now tussling on the floor and Mrs. Peabody stood at the stove stirring something steamy in a large pot. She turned and shook Anastasia's hand when Henry introduced them.

"Now look at that nice haircut you have," she said. "I just don't know what to make of Henrietta's. Seems as if they just shaved her down to nothing."

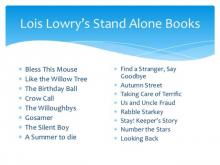

The Willoughbys

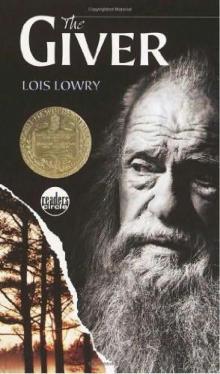

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver