- Home

- Lois Lowry

All About Sam Page 7

All About Sam Read online

Page 7

They howled with laughter. They laughed until they were exhausted.

The next morning, bright and early, Sam went with his mother to the barber for repairs. For four weeks, until his curls grew back, he had the most interesting punk hairdo in town. It was even better than his friend Adam's.

12

"Katherine," Sam's daddy said at dinner, "this is terrific fish chowder."

"Thanks," said Sam's mother. "It is good, isn't it? It's fattening, though. All that cream."

Sam looked up from his own chowder. He liked it because he could mash up crackers in it, which was fun. But he wasn't thinking about his chowder. He was thinking about something that he had just noticed for the first time.

"Why," Sam asked his father in a thoughtful voice, "do you call Mommy 'Katherine'? But I call her Mommy?"

"Well," Dr. Krupnik explained, "I can't call her Mommy because she's not my mother. My mother was named Ruth."

"Did you call her Ruth?" asked Sam.

"No, I called her Mother. But her name was Ruth."

"What was your daddy's name?"

Sam's father grinned. "His name was Sam. Like you. That's why we named you Sam when you were born. It was Anastasia's idea."

Sam frowned. It was all very puzzling. "But why do you call me Sam? I know my name is Sam. But your name is Myron, and I don't call you that. If I call you Daddy, why don't you call me Son? And why don't you call Mommy Wife?"

His father said, "Well, I suppose I could do that." He looked at Mrs. Krupnik and said, "Could I have another helping of chowder, please, Wife?"

"Of course, Husband," Mrs. Krupnik said, and she took his bowl to the stove where the pot of chowder was. "Would you like some more, Son? How about you, Daughter?"

Sam and Anastasia both said "No, thank you" and giggled.

It was all very confusing, Sam thought, as he finished his dinner.

Anyway, what he really wished—he hadn't told them this—was that they would call him He-Man.

Sam had daydreams about being bigger. Not only bigger, but also stronger and more powerful. He wanted to be someone who could catch criminals, beat up bad guys, fly airplanes, shoot rockets, and end up being He-Man of the Whole World.

All the guys at Sam's nursery school wanted the same thing. Their favorite games had to do with blasting off and zooming and bashing. They were so noisy that Mrs. Bennett was always saying, "Time Out, guys," and then they would listen to her read a story about Babar or Madeline or Curious George.

Sam loved listening to stories. And sometimes he liked to play the quiet games. He liked playing house with Leah and Rosie and Skipper when they would cook pretend dinners on the little stove and serve the dinners to the stuffed animals that they propped up in chairs.

But sometimes, while playing house, Sam would have an urge to race around with the pretend dinner in its plastic dish, and bomb the animals instead of feeding them nicely.

Then Rosie would always start to cry, and Mrs. Bennett would have to say, "Time Out, Sam."

Time Out meant that he had to sit quietly in the big green chair.

Sometimes Sam had Time Out several times every morning. He didn't mind that. Football players had Time Out, too; he saw it on TV when his daddy watched the Patriots.

"Why do they have Time Out?" Sam asked his daddy. "Were they bad?"

"No, they just need to take a rest and to think a little bit," his daddy explained.

So that's what Sam did, too, at school, when Mrs. Bennett said "Time Out," and Sam had to sit in the green chair. He rested and thought.

Mostly, he thought about being a He-Man.

"Do I have big muscles?" Sam asked Anastasia. He had pushed up the sleeve of his shirt, and he showed her the top of his arm.

Anastasia was busy with a school project. She was at her desk, with her feet wrapped around the rungs of the chair, and a pencil tip in her mouth. She glanced over at Sam.

"No, I wouldn't say so," she said. "Your arms are kind of skinny."

Sam stuck out his lower lip. "Well," he asked her, "how can I get big muscles?"

Anastasia glanced over again, impatiently. "You have to pump iron," she said. "There's this guy at the junior high, Ben Fraser, who has humungous muscles. And he got them by pumping iron."

"How can I—" Sam began.

But Anastasia interrupted him. "Sam," she said, "I'm busy. Please quit bothering me, okay?"

Sam sighed and wandered away from Anastasia's bedroom. He went downstairs. He thought about pumping iron.

He knew what an iron was. His mother had one. She kept it in the pantry on a shelf, with its cord all twisted around it. His mom was allergic to the iron, she said.

Sam went to the pantry and lifted the iron down very carefully from its place. He took it up to his room.

Then he went to his mother's closet. He kicked aside her sandals and her torn sneakers on the closet floor. He crawled inside the closet and looked around. He saw a couple of old pink slippers. Those weren't what he wanted.

Finally he found what he was looking for, inside a shoebox stacked with others in a corner of the closet. They were high-heeled and black. There were two of them. Pumps.

He took one of the black pumps to his room and laid it carefully on his bed beside the iron.

Then he tried to figure out how to do it. How to pump iron.

But it was a mystery. He could do it backward. He could iron the pump. He did that for a while, but it was boring, and it didn't make big muscles at all.

But he simply couldn't figure out how to pump the iron.

Maybe there was another way. Sam went to his mother and asked her. She was in the big studio where she painted, and she was working at her easel, humming and holding a paintbrush with a blue-daubed end in her hand.

"Hi, Sam," she said. "What's up?"

"Do you know how to make big muscles on someone?"

"Well," said Sam's mom, "if I were making a picture of a person, and wanted to make big muscles, I would do it like this." She pulled out a large sheet of paper, drew a man very quickly with a marking pen, and then added a fat bulge on each of his arms. "See?" she said. "Big muscles."

Sam looked. The picture looked a little like Popeye.

"Yeah," he said, "but if it was a real person, not just a picture person, how would he get big muscles? How did Popeye get his big muscles?"

His mother laughed. "Spinach, of course. Don't you remember how Popeye gobbles spinach every time he needs more strength and bigger muscles?"

Of course. Sam did remember.

And he remembered something else. He remembered that there was some leftover spinach in the refrigerator.

Sam didn't like leftover, cold spinach very much. But he went to the refrigerator anyway, took out the dish that held the spinach, and ate some.

Yuck. It tasted awful.

He checked his muscles. No change.

Another big bite. YUCK.

And he checked again. Still no muscles.

Sam sighed and reached for the bowl of spinach one more time, just as the back door opened. His father was home.

"What are you eating, Sam?" Daddy asked. He set his briefcase down, came over to the table where Sam was sitting, and peered into the bowl. "It looks like cold spinach."

"It is cold spinach," Sam said with his mouth full.

"Do you mind if I ask why you are eating something so disgusting? Especially when there's good stuff in the refrigerator, like—let's see—apples?"

"I need big muscles," Sam said.

"You do?" his daddy asked. "Why?"

Sam thought about that. "If I had big muscles," he said at last, "Nicky would never ever bite me at school. And no monster would ever dare to come live in my closet. I could chase bad guys. And everybody would call me He-Man."

"Well," his dad said, "I guess that's true. But why are you eating cold spinach?"

"This is how Popeye gets his big muscles."

Sam's daddy sat down. "I'd forgotten that, Sam, but yo

u're right. That is how Popeye gets his muscles. And when I was a kid, I tried to get them the same way. But you know what?"

"What?" Sam asked gloomily, reaching for another bite of yucko cold spinach.

"It doesn't work for regular people, only for Popeye."

"It doesn't?" Slowly Sam put the spinach back into the bowl.

"Nope. I thought I'd better tell you before you gave yourself a spinach stomachache."

"But how did you get your big muscles?"

"Me? I don't have big muscles. I'm Mister Flabbo," said Sam's father. "Feel." He guided Sam's hand to the top of his arm, and Sam poked. Through his father's jacket, the arm felt pudgy and soft.

"Anyway," his father said, "you don't want to be like Popeye. He wears terrible clothes."

Sam thought about Popeye's clothes. "They're not so bad," he told his father. "He wears a sailor suit."

"I happen to know, Sam, that your mother bought you a sailor suit. And you absolutely refused to wear it. Remember that day when you were supposed to go to a birthday party, and Mom tried to get you to wear the sai-"

"Yeah," Sam muttered. It was a day he had tried to forget. He had behaved very badly. So, in Sam's opinion, had his mother.

"And another thing about Popeye—" Sam's father went on. "I know you'll hate this!"

"What?"

"He smokes a pipe."

"That's right!" Sam said. "Just like you! Even though Mom and Anastasia and I always always tell you to quit, and Anastasia brought home all those booklets from the American Long Sausage Nation."

"American Lung Association," his father corrected him, with a guilty look. "And I am going to quit, I really am. Very, very soon. Probably next week. Or if not next week, the week after that, for sure."

Sam's daddy looked so unhappy that Sam reached over and stroked his arm to let him know that he loved him, even if he did smoke a pipe.

"Good old Mr. Flabbo," Sam said. "I love you."

"Thanks, Sam," his daddy said. "I love you, too. Let's you and I start doing some exercises together, so we can work on the old muscles."

Sam grinned. He put the bowl of spinach back in the refrigerator. "Come on," he said to his daddy. "Let's go pump iron."

13

Sam slithered on his belly up the stairs and into his sister's bedroom. Her door was partly closed, so he slithered in very carefully through the open part, making no noise.

Slither, slither, slither.

Anastasia didn't see him. She was on her bed, writing in her notebook.

Anastasia was always writing in her notebook.

"It's my private notebook," she had told Sam. "And don't you ever dare peek into it. Because I have ways of knowing if you do."

"What ways?" Sam asked. "I could do it while you're at school, and you would never, ever know." (Anastasia never took the private notebook to school.)

"Yes, I would. Sometimes I put an invisible hair across the cover, and if the hair is dislodged I know a spy has been into my notebook."

"Lemme see. I want to see the invisible hair," Sam had said.

But Anastasia had said no. "Just keep your mitts off of it," she told him. "People my age—thirteen—have private stuff, and they don't want their little brothers messing around with it."

"People my age have private stuff, too," Sam had told her.

He didn't, really. Didn't have any private stuff. But he liked to try to make himself invisible, which was a way of being very private, and that was why he was slithering invisibly into Anastasia's room.

"BOO!" Sam shouted, leaping up suddenly, beside his sister's bed.

Anastasia jumped, startled. She dropped her marking pen.

"Sam!" she said in an irritated voice. "Cut it out. You scared me. What are you doing, creeping around like that?"

"I'm being a lizard," Sam explained.

Anastasia laughed. "Well, you make a pretty good lizard, Sam. Why don't you slither downstairs and eat some insects? That's what lizards do. Go out in the yard and find a nice juicy caterpillar for lunch, okay?"

Sam thought about that. He thought about a huge, fuzzy, juicy caterpillar, placed right in the center of a piece of whole-wheat bread, maybe with a little mustard dabbed on him.

Suddenly Sam didn't want to be a lizard anymore, not even for one minute longer.

"Will you play with me?" he asked Anastasia. "I'm not a lizard anymore. I'm a boy again."

Anastasia looked up from her notebook. "I will a little later, Sam. We can go outside and I'll give you a ride on the back of my bike, okay? But not right now. Right now I'm making up a secret code, and I need to do it all by myself, without any interruption."

Sam's eyes widened. "What's a secret code?" he asked.

"Oh, it's complicated, Sam. It's when you say one thing but mean something else. Or write one thing but mean something else. Understand?"

Sam shook his head no.

"Well, for example..." Anastasia hesitated. "Sam," she asked, "if I explain this code to you, promise me you won't tell anyone?"

Sam nodded.

"Do you solemnly swear?"

Sam gulped. He knew that swears were bad. There was a kid at nursery school who was always saying swears, and Mrs. Bennett did not find it amusing at all, not even for one single minute. (It was Sam's best friend, Adam.)

"I solemnly swear," Sam whispered, glancing around to be certain no one could hear.

"Well," Anastasia explained, "I've made a list of all the boys I know. Robert Giannini and Steve Harvey and Eddie Fox and—well, all the boys I know. See?" She tilted the notebook so that Sam could see a list of names written in green ink.

"Now, here's the code part," Anastasia went on. "I've written words after each boy's name, but the words don't really mean what they say. So if I wrote love, that really means 'hate,' see? And despise means 'love'. And my friend Meredith has the code, too, so she can understand. And if I call Meredith up and say, 'I despise Steve Harvey'—well, Meredith could look at her code notebook and see that would really mean that I love Steve Harvey. But no one else would know, because they wouldn't know the code."

Sam stared at his sister.

"See?" Anastasia asked.

"I guess so," said Sam, even though he didn't, really.

"Don't forget that you can't tell anyone. You solemnly swore, remember?"

"Yeah." Already Sam was sorry that he had solemnly sworn. It hadn't been worth it. He dropped to his belly and slithered out of Anastasia's room and down the stairs. He was a new kind of lizard: a kind that didn't eat bugs, only peanut butter.

"What were you doing upstairs?" asked Mrs. Krupnik, as Sam ate his sandwich. He had slithered into the kitchen, explained about the peanut-butter-eating lizard, and his mother had realized that it was probably feeding time in the lizard world.

"I learned about code," Sam told her.

"Code?" his mother asked, wrinkling her forehead.

"Yeah, that's when you say one thing but you really mean something else."

"Like what?"

Sam sighed. He couldn't tell about Anastasia's code because he had solemnly sworn. But suddenly he thought of something else.

"Like Mr. Flabbo," he said. "If I said Mr. Flabbo, you know who I would mean, don't you?"

His mother laughed. "Sure. You'd mean Daddy."

"Right. Because Mr. Flabbo is code for Daddy. And if I said, 'I hate Mr. Flabbo,' it would really mean 'I love Daddy.'"

"Oh." His mother looked confused.

Sam looked around the kitchen. On the floor in front of the washing machine there was a huge stack of dirty clothes. He recognized the shirt he had worn yesterday, and he recognized the chocolate milk he had spilled on that shirt at dinner last night. He saw Anastasia's socks and his dad's pajamas. He knew how his mother felt about laundry.

"If you said, 'I love doing the laundry,'" Sam explained, "that would be code, and it would really mean—" He waited for his mother to catch on.

She laughed and sipped her coffee. "I guess I s

ee. But I hope you won't say you hate anything, even in code, Sam. Okay? Because hate is such a yucky word. Even for laundry."

Sam nibbled out the rest of the good part of his sandwich and arranged the crust in an on his plate. "Yeah, okay," he said. Actually, he didn't think hate was a yucky word. Broccoli was much yuckier.

Sam went outside and wandered across the yard to visit the Krupniks' next-door neighbor. Her real name was Gertrude Stein. But Sam never called her that. He liked to call her Gertrustein.

Gertrustein was very old. Sam wasn't sure how old, maybe two hundred.

She had a grouchy face, and when Sam had seen her for the first time, he had been frightened by her face. But later, when he got to know Gertrustein, when they became good friends, he realized that she was actually a smiling sort of person. But her skin had drooped, so it hung down in a grouchy look, and sometimes it was hard to see the smile underneath.

Gertrustein was on her back porch, hanging a dishtowel on the clothesline there. She always moved very slowly. Her arms and legs ached all the time, she had explained to Sam, and that was why she moved so slowly.

"Hi, Sam!" Gertrustein said when Sam came up the steps. "What a nice surprise!"

She lived all alone. She had no husband, no children, no grandchildren, and no dog or cat. So she was always glad to see Sam.

"If I didn't have you to talk to," she had once told Sam, "I would probably forget how to talk."

Sam thought it was the saddest thing in the whole world, to have drooping skin that gave you a grouchy face, to have aching arms and legs so that you had to move slowly, and to live all alone so that you might forget how to talk.

But Gertrustein didn't seem to mind. Almost every day she made cookies.

"I expect you might be willing to do me a favor and eat a cookie or two," she said to Sam.

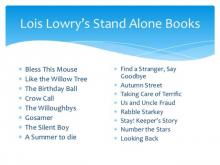

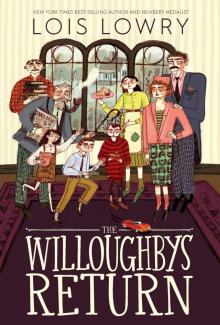

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

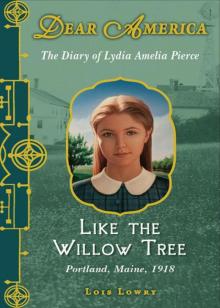

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

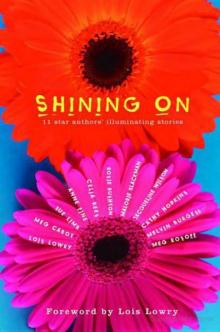

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver