- Home

- Lois Lowry

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Page 8

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Read online

Page 8

With both gerbils tightly restrained in one hand, she replaced the fruit in the basket, turned off the light, and left the studio. In the hall, she met her father coming out of his study.

"That was fast," he said. "Are you all finished already?"

Anastasia held her handful of gerbils behind her back. "I am for now," she said.

He hesitated. "Anastasia, I need to speak to you privately," he said. "Do you have a few minutes?"

"Sure," she told him, with her hand still uncomfortably behind her back. All of a sudden, her hand was wet. One of the gerbils had peed in her hand. "But I have to go upstairs for a minute first."

"I'm going to go get some coffee," her father said. "I'll meet you in the study."

Anastasia took the gerbils to her room and put them into the cage. She counted. Eight down, and three to go.

She went to the bathroom to wash her hands. Gerbil pee, for pete's sake, she thought. The things I have to go through. Talk about disgusting.

Sam wandered by the bathroom and looked in. "Did you find him?" he asked. "Was it Dopey?"

"It was Romeo and Doc," she told him. "And Romeo was disgusting. He has no self-control."

"So, Dad, what's up?" asked Anastasia. "What do you want to talk to me about?"

He looked uncomfortable. "I find this very embarrassing," he said.

Anastasia was astonished. "You're not going to talk about the facts of life, are you, for pete's sake? You and Mom already did that, years ago!"

He laughed, and lit his pipe. "No. This is a problem I have, and I don't want your mother to know about it."

"But you and Mom don't have any secrets from each other!"

"Normally we don't," he admitted. "But you know your mother's still upset about that Coletti child. I just hate to add another problem to her list, especially one as bizarre as this. This one would really blow her mind."

He has a mistress, Anastasia thought suddenly. My father has a mistress. He's fallen in love with one of his students: a sweet young thing with big eyes and dangly earrings, and they're planning to run off together and be vegetarians, and maybe join a weird religion, and probably he's going to take the stereo with him, too.

"Well, it might upset me, too!" she said angrily. "Didn't you ever think of THAT?"

"There was this movie awhile back—I'm sure you saw it," her father said.

Anastasia tried to think of a movie in which a middle-aged man ran off with a young vegetarian.

"An Unmarried Woman?" she asked suspiciously.

"No," he said. "It was called Poltergeist."

He doesn't have a mistress, Anastasia thought. I knew it couldn't be that. Not my good old dad. She relaxed. "I hated Poltergeist," she said.

"Me too. And I've never believed in that stuff—ghosts that move objects around and break things."

"Idiotic," said Anastasia.

"Right. That's what I always thought. But, Anastasia, I think I have one."

"A ghost?"

Her father nodded miserably. "A poltergeist. Right here in my study."

Anastasia looked around the study, her favorite room in the whole house besides her own bedroom—and lately she'd begun to hate her bedroom, because it smelled like gerbils. The study was lined with bookcases filled with books. There was the fireplace, her father's big desk, the soft couch with its piles of bright-colored pillows, her mother's paintings on the walls.

"Here?" she asked in amazement.

He sucked on his pipe, looked around, and shuddered. "I know. It sounds ridiculous. But lately things have been moving, just the way they did in that movie. Earlier this evening, I was sitting at my desk correcting some papers, and suddenly I heard a metallic sort of clunk."

"A clunk?"

"Exactly. And when I looked up, my hubcap ashtray was still vibrating. It had jumped up and down."

They both stared at the hubcap.

"And it's happened before. The hubcap jumps, but when I look at it, there's nobody there. Sometimes I've thought that Sam must be hiding behind the couch, playing tricks. But he isn't. There's never anybody there.

"And once," he went on, "I saw a book move. Up there, in the bookcase. Just a fraction of an inch. But I saw it, Anastasia. It jumped out of the bookcase a fraction of an inch. Look: I left it that way. See how that one book is sticking out farther than the others?" He pointed.

Anastasia looked, and began to grin. "It's Dopey," she said.

"Don't say that," her father said. "It's Hemingway."

Out of the corner of her eye, Anastasia saw a sudden, swift, darting movement between the desk and the couch.

"Dad," she whispered, "sit very, very still."

He froze.

Moving silently, inch by inch, Anastasia approached Dopey, who was hunched over, hiding behind the leg of the couch. With a quick thrust of her hand, she grabbed him. She held him up, tail dangling. "There's your poltergeist, Dad!"

Her father adjusted his glasses and looked carefully at the squirming Dopey.

"A gerbil," he said. "I thought you had your two gerbils in your room, Anastasia. And why is his head pink?"

Anastasia sighed. "Dad," she said, "I'm going to tell you something. But you must promise not to tell Mom."

"Well, you're right, Anastasia," her father said, emptying the tobacco from his pipe into his hubcap, "we certainly mustn't tell your mother. How many did you say are still missing?"

"Now that I've caught Dopey, two more."

The door to the study opened a few inches. "Don't come in, Mom," said Anastasia hastily, holding Dopey behind her. "Dad and I are having a private conversation."

"It's me," said Sam, poking his head around the door. "Grumpy and Sleepy!"

"Everybody's grumpy when they're sleepy, Sam," said his father. "Come on, I'll take you up to bed."

"No, look!" Then he hesitated. "Can I show Dad?"

Anastasia nodded, chuckling.

Sam held up his two fists, with a tail dangling from each. "In my slippers!" he said. "They were in my bedroom slippers!"

Science Project

Anastasia Krupnik

Mr. Sherman's Class

On October 13, I acquired two wonderful little gerbils, who are living in a cage in my bedroom. Their names are Romeo and Juliet, and they are very friendly. They seem to like each other a lot. Since they are living in the same cage as man and wife, I expect they will have gerbil babies. My gerbil book says that it takes twenty-five days to make gerbil babies. I think they are already mating, because they act very affectionate to each other, so I will count today as DAY ONE and then I will observe them for twenty-five days and I hope that on DAY 25 their babies will be born.

This will be my Science Project.

Day Three.

My gerbils haven't changed much. They lie in their cage and sleep a lot. They're both overweight, because they eat too much, and they resemble Sonya Isaacson's mother, at least in chubbiness.

In personality, they resemble my mother. They're very grouchy.

Day Three Continued.

People who have serious emotional problems sometimes have difficulty doing real good gerbil-observation because they suffer from inability to concentrate. I myself have serious emotional difficulties so I have this problem.

As part of my Science Project I will talk about serious emotional problems. I will tell you what someone named Freud says about this.

The division of the psychical into what is conscious and what is unconscious is the fundamental premise of psycho-analysis; and it atone makes it possible for psycho-analysis to understand the pathological processes in mental life, which are as common as they are important, and to find a place for them in the framework of science.

Day Five.

My gerbils gave birth to premature babies. Instead of twenty-five days, it took them only five days to have babies.

Now I have eleven gerbils, and their names are Romeo, Juliet, Happy, Sleepy, Sneezy, Dopey, Grumpy, Bashful, Doc, Snow White, and Prince.

<

br /> I also have a psychiatrist. His name is Freud. He Is dead. But there is no need to be grossed out by that because with some psychiatrists It doesn't seem to matter much if they are alive or dead.

Day Twenty-five.

I have not written anything for a long time because I have felt very tired and it may be that I have a wasting disease. My dependent relations have no sympathy for someone with a wasting disease, I am sorry to say.

Here is what my psychiatrist says about dependent relations:

...the derivation of the super-ego from the first object-cathexes of the id, from the Oedipus complex, signifies even more for it. This derivation, as we have already shown, brings it into relation with the phylogenetic acquisitions of the id and makes it a reincarnation of former ego-structures which have left their precipitates behind in the id.

To identify my gerbils scientifically, I have colored their heads.

RED—ROMEO BROWN—GRUMPY

BLUE—JULIET BLACK—SLEEPY

YELLOW—HAPPY PINK—DOPEY

GREEN—SNEEZY TURQUOISE—SNOW WHITE

ORANGE—BASHFUL WHITE—PRINCE

PURPLE—DOC

This will make it easier for me to know who is who, in case one of them has babies or something.

To identify my psychiatrist, I have put a large MAGENTA spot on his head. (There is, of course, no chance that my psychiatrist will have babies.)

Day Twenty-nine.

My gerbils have disappeared.

My gerbil book says this about disappeared gerbils: "If, in the process of escaping, the gerbils have been frightened, it is best to just sit very still in the middle of the floor until the gerbils come out of hiding on their own."

But my scientific assistant, Sam, and I sat very still in the middle of the floor for one hour, and my scientific assistant fell sound asleep while we waited. But the gerbils never appeared.

I think that by now there are eleven gerbils loose all over the house. And if my mother sees even ONE of them she is likely to have a nervous breakdown.

My mother doesn't even know I HAVE eleven gerbils.

And my psychiatrist is no help at all. He has his own problems: a villain has painted his nose blue.

Day Fifty-nine.

I have not worked on my Science Project for a long time because I have been extremely emotionally disturbed. One of the scientific things about gerbils is that they can cause you severe emotional problems.

My gerbils are all found and are back in their cage. Here is where they were found:

ROMEO (RED)—STUDIO, EATING A 4-H PENCIL

DOC (PURPLE)—STUDIO, EATING A 4-H PENCIL

JULIET (BLUE)—KITCHEN, EATING A RICE KRISPIE

HAPPY (YELLOW)—PILE OF LAUNDRY, EATING A TEE SHIRT

SNEEZY (GREEN)—VACUUM CLEANER INSIDES

BASHFUL (ORANGE)—COAL CAR OF OATMEAL-BOX TRAIN

GRUMPY (BROWN)—LEFT SLIPPER

SLEEPY (BLACK)—RIGHT SLIPPER

DOPEY (PINK)—STUDY, BEING A POLTERGEIST

SNOW WHITE (TURQUOISE)—SNEAKER

PRINCE (WHITE)—FLOWERPOT, EATING BEGONIA

Finding the gerbils has been a very traumatic experience for me.

My next scientific project will be finding a way to get rid of the gerbils. I plan to work very hard on this

"Sigmund," said Anastasia, after she had checked the latch on the gerbil cage for the fifteenth time, "you haven't been very helpful to me through all of this."

She looked over at him. He didn't seem to be smiling anymore. He was staring at her with a stern look.

"What's wrong, Sigmund?" she asked.

Anastasia got up and went over to the head of Freud. The smile lines at the corners of his lips had begun to fade. He was getting his old mouth back, the one that looked serious and dour.

She reached for the black marker to replace his smile. Then she hesitated.

"Maybe it isn't a good idea to have a psychiatrist who always agrees with everything I say, and smiles," she told the head of Freud. "What do you think?"

He looked very sternly at her.

"Well, all right, you don't have to get mad," Anastasia grumbled. She went to her bed and lay down, staring at the ceiling.

"What would you do, Sigmund, if you had to get rid of eleven smelly gerbils?"

She glanced over. He was frowning.

"I know what you'd do," she said. "You'd probably give them to someone you hated. You look as if you hate a lot of people.

"But I don't hate anyone that much," Anastasia sighed. "I used to hate my mother and father. That was a couple of months ago. But now I don't hate them anymore.

"Now I like them. My father was really nice when I told him about the gerbil problem. I suppose having all this psychiatric counseling helped me adjust to my parents."

Anastasia yawned. "And, of course, there were the hormones. But my hormones are gone, all of a sudden.

"First, the gerbils disappeared," she told Freud, yawning again, "and then the hormones did. Life is just one weird surprise after another."

8

Anastasia trudged home from school with Meredith, Sonya, and Daphne.

"What do you guys want to do this weekend?" she asked her friends. "Go to the movies?"

"I want to hang out at McDonald's," said Daphne. "This guy in the ninth grade—Eddie Wolf—works there weekends. He's gorgeous."

"DAPHNE," said Anastasia grouchily, "You're becoming very boring. All you're interested in is guys."

"I told you," Sonya said. "It's Stage Two of Adolescence. It's normal."

"Well, it's boring," said Anastasia.

Meredith made a snowball and threw it at a tree. "Guess what," she said. "I don't think it's boring. I think I'm entering Stage Two myself. I'll go to McDonald's with you, Daph."

"Not me," said Sonya. "I have to work on my Science Project. It's due in three weeks."

Anastasia kicked a chunk of snow. "Mine's just about done, but it isn't any good. I'm probably going to flunk."

"You can't flunk," Daphne pointed out. "Projects for the Science Fair are extra-credit. You don't even have to do one. I'm not doing one. I don't have time."

"Yeah, because you're always out chasing guys," said Anastasia. "Here's my street," she added. "I'll see you. Call me if you want to go to the movies." She waved, and turned the corner toward her house.

"Hi, Anastasia!" Sam greeted her as she came through the back door. "Guess what? Nicky Coletti didn't come to nursery school today, so I had all the blocks to myself!"

Anastasia hung her jacket in the back hall. She sat down to unlace her snowy boots. "That's nice, Sam. Hi, Mom. Did you have a good day today?"

Her mother was at the kitchen counter, peeling potatoes. Her back was turned. "No," she said, without looking around. "I did not."

Oh, great, thought Anastasia. Her mother was in a bad mood. Best to ignore her for a while; maybe it would go away.

"Whoops!" said Sam. "I almost forgot. Mom, my nursery school teacher sent you a note. It's here, in my pocket." He reached into his jeans and took out a piece of paper.

Mrs. Krupnik turned. Her face was very mad. "My hands are wet," she said. "Read it to me, Anastasia."

Anastasia unfolded the paper and read it aloud.

"Dear Early Learning Center Parents," she read. "One of our children, Nicky Coletti, has had an unfortunate accident and will be out of school for six weeks, with both legs broken. I'm sure the Coletti family would appreciate cards or small gifts, to make Nicky's convalescence easier."

Anastasia looked up. "Then it tells the Colettis' address," she added.

Sam had a broad grin. "Six weeks?" he said gleefully. "I don't get bashed over the head for six weeks?"

"Sure sounds that way," said Anastasia. "I wonder how she broke her legs."

"Probably kicking somebody," suggested Sam.

"Maybe climbing up someplace to smash a cookie jar," said Mrs. Krupnik, who was still upset about their blue cookie jar, which she had loved.<

br />

"I bet her father is a Mafia person," said Anastasia. "And he finally got mad and broke both her legs."

"We're being terrible," said Mrs. Krupnik, wiping her damp hands on a paper towel. "It's a shame, to have a child injured. I suppose we ought to send a card."

"A present," said Sam. "I'm going to send big fat ugly Nicky Coletti a present. I'm going to send her dog poop!"

"Sam," said his mother sternly. "That's not nice."

Sam pouted. "I am," he muttered under his breath. "I'm going to send her a whole lot of smelly dog poop."

Mrs. Krupnik had gotten her angry face back. "Listen, you two," she said. "I've been waiting for you to come home, Anastasia, because I have something to discuss with you."

She reached up to a shelf beside the sink and took down a folded piece of paper. "I found this in the study this afternoon. And I want an explanation. I don't want any made-up excuses or stories or evasions. I want a full disclosure on this subject. And I want it RIGHT NOW."

Anastasia sighed, and sat down. She didn't have any idea what her mother was talking about. She didn't have any idea what the folded paper was.

But Sam, apparently, did. He was looking at it, and his eyes were wide. "Uh-oh," Sam said.

Mrs. Krupnik handed Anastasia the paper. It had typing on it—obviously Sam's typing, uncapitalized and all over the page.

Apprehensively, Anastasia read it:

"You really are getting pretty good at reading and writing, Sam," said Anastasia feebly. "And typing," she added.

"Does this mean what I think it means?" asked Mrs. Krupnik very grimly.

Sam was sucking his thumb vigorously.

"Well," Anastasia started, "in a way I guess it does."

"What do you mean: 'in a way'? Are there, or are there not, eleven gerbils?"

"Ah, yeah," said Anastasia, "there are."

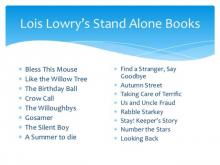

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver