- Home

- Lois Lowry

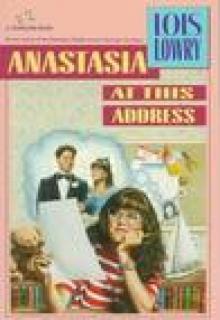

Anastasia at This Address Page 9

Anastasia at This Address Read online

Page 9

"That's terrible!" Myron Krupnik said, after Anastasia had explained the laughter during the ceremony.

Mrs. Krupnik shrugged. "What's so terrible?" she asked. "A wedding is supposed to be a joyous occasion. And the minister didn't seem to mind. Most weddings are so serious and solemn—maybe he liked the change."

"Maybe," her husband acknowledged. "He seemed in good spirits at the reception. I even saw him dancing with his ex-wife."

"Speaking of dancing," Anastasia said, remembering something suddenly. "You know what? Me and Meredith and Sonya and Daphne—"

Her father raised his eyebrows at her.

"I meant," she corrected, "Meredith and Sonya and Daphne and I. We invited Steve and Eddie and Norman and Kirby so we'd have somebody to dance with at the reception! And they didn't dance! Not one of them! Not once!"

"Seventh-grade boys never dance," her mother pointed out. "You've complained about that to me a million times."

"I know," Anastasia said, making a face. "But we thought they would at a wedding, for Pete's sake! I'm giving up boys for real."

"Anyway," Mrs. Krupnik said, "you did dance a lot, Anastasia. Dad danced with you, and—"

Myron Krupnik cringed. "I'm a terrible dancer," he said apologetically. "I hope I didn't ruin those beautiful blue shoes, Anastasia."

Anastasia looked down at the floor, where her shoes were lying by the couch. "They're a little smudged is all," she said. "No problem."

"And you danced with every single usher," her mother went on. "They were really awfully sweet, to dance with you kids."

"Yeah," Anastasia agreed. It was true—each of the ushers had danced with the junior bridesmaids. And her father had danced with her, though he was correct that he was a terrible dancer. Sonya's father, Dr. Isaacson, had danced with her, too.

Steve, Eddie, Kirby, and Norman had spent the entire reception eating endless amounts of food from the buffet table and hanging out near the band, talking to the musicians when they weren't playing. Talk about adolescent behavior.

"About the ushers," her mother was saying.

"What about them?"

"Well, there was one who was especially tall and good-looking. The one who came down the aisle with you, Anastasia, at the end of the ceremony?"

Oh, no, Anastasia thought. I tried so hard to keep them apart. But now is when she's going to say that he came up to her and said, "Hi, Swifty!" and she said, "You must mean my daughter," and then he said—

She gulped. "That was, ah, Meredith's Uncle Tim," she said. "Mom," she went on in a nervous voice, "I have a confession to make—"

But her mother wasn't paying attention. "He acted very strange," she said. "He kept staring at me."

"Staring at you?" asked her husband.

"Yes. He stared at me knowingly. That's the best way I can describe it. And he kept starting toward me as if he were going to say something."

"Did he? Say anything, I mean?" Anastasia asked apprehensively.

"Good heavens, no. Every time I saw him start toward me with that strange look, I went to the ladies' room. Or I grabbed you, Myron, and started dancing.

"And then, just as we were leaving," her mother added, "he was there in the doorway, and I could swear that he whispered, 'See you tomorrow,' when I walked past. Isn't that strange?"

Anastasia felt uneasy. "I understand he's a rather strange person," she said, feeling a little disloyal to Septimus Smith. "He drives a Porsche and leads a glamorous life. I think you were very wise not to talk to him."

"So do I," said her father.

They were all silent for a moment, remembering the wedding. Anastasia was suddenly remembering something else, as well: Septimus Smith would be knocking on the door of her house tomorrow at 2 P.M.

"Mom? Dad?" she asked. "Can we do something tomorrow, just as a family? Can we first go out to brunch, maybe about eleven o'clock, and then after that we can take Sam to the dinosaur exhibition at the Science Museum?"

"Sounds good to me," her father said.

"Sounds great to me. I'd love it," her mother said. "I think I'll make a pot of coffee, " she added, yawning. "Anastasia, can I get you anything? Milk? A Pepsi?"

"No, thank you. I just remembered something I want to do upstairs."

In her stocking feet, Anastasia went upstairs and into her brother's bedroom, where Sam slept soundly, wearing his sailor suit.

"Sam," she said into his ear, but he didn't stir.

"Sam," she said more loudly, and shook his shoulder.

"Mmmmmmm?" Sam murmured.

"I've decided to sell you back your sloop, " Anastasia said.

"Mmmmmmm?" He rubbed his eyes sleepily.

"Your sloop, Sam. You can buy it back, like you wanted."

"No. I don't wanna." He turned over and buried his face in the pillow."

"But Sam!" She shook him again. "You said you'd give me fifty cents. Remember?"

"No," he said in a muffled voice. "I changed my mind."

"Sam, I really want you to have that sloop back."

He lifted his head, opened his eyes, and looked at her groggily. "You pay me, then. A dollar."

"A dollar?"

But Sam had put his head back down and was breathing deeply.

Anastasia stared at him for a moment. Finally she sighed. She went to her room, picked up the little red sloop from the windowsill, took a crumpled dollar bill from her wallet, and returned to Sam's bedroom.

"Sam," she said in an irritated voice to her soundly sleeping brother, "you're going to be a great businessman someday. But I hope you have a whole lot of trouble managing your portfolio." She left the sloop and the money on the table beside Sam's bed.

Back in her room, she tore up the letter she had written the night before. She took out a fresh sheet of stationery and began to write a new one.

When her mother knocked on her bedroom door, Anastasia quickly slid a magazine over the letter.

Mrs. Krupnik entered the room and sat down on Anastasia's bed. "You know," she said, "being at the wedding made me think about what we were talking about recently. All the things you renounce if you renounce marriage."

Anastasia looked at her mother questioningly.

"Did you know that I had a Newfoundland dog when I was a kid?" her mother asked.

"Sure. I've seen a million pictures of you with him. You told me his name was Shadow."

"Right," her mother said, smiling. "Good old Shadow. I really love dogs. But you know your dad's allergic to them. So I've had to—"

"Renounce dogs?"

"Yeah," her mother said sadly. "And also, Anastasia, remember when you asked me what a sloop was? And without even looking it up I was able to tell you what a sloop was? A single-masted sailboat rigged fore and aft?"

"I sold the sloop back to Sam," Anastasia told her.

Her mother chuckled. "Good. He'll be pleased. But listen, Anastasia—the reason I know about sloops is because I used to sail a lot when I was young. My father had a sailboat. And I love sailing. But when I got married: well, you know that your dad—"

Anastasia nodded. "Seasick," she said. "Dad gets seasick."

Mrs. Krupnik nodded. "I had to renounce sailing," she said with a sigh.

Then she brightened. "But what I wanted to tell you, Anastasia, is that I don't regret it for one instant. Because look at everything I got in return. Downstairs, in the living room, your dad—he's sound asleep on the couch, with the newspaper over his face, same as always."

Anastasia giggled. "Is he snoring? Is he fluttering the newspaper?"

"Yep." Her mother grinned. "And on the second floor, there's old Sam, sound asleep in his dumb sailor suit, with a three-color tattoo on his arm."

"Good old Sam," Anastasia said, smiling.

"And here, on the third floor, in this messy room—" Her mother looked around Anastasia's bedroom, smiling. She stood up, put her arms around Anastasia, and kissed the top of her head. "I have my wonderful daughter who looked so beautiful today that I alm

ost burst into tears, I was so proud."

"Thanks, Mom," Anastasia said.

"I wouldn't trade any of that for a dog or a sloop," her mother said firmly. She turned to leave. "Oh," she reminded Anastasia from the doorway, "earlier, you started to say that you had a confession to make."

"It was just something dumb," Anastasia said, embarrassed. Quickly, in her mind, she realized that she didn't want to tell her mother about her relationship with Septimus Smith. Now that it was over—and it would be as soon as she mailed this letter in the morning—there was no need for her mother ever to know that she had done something so foolish.

Of course, she realized at the same time, there were plenty of other dumb things she could confess.

Her mother waited.

Anastasia shrugged. "Well," she confessed, "it was this. I don't have the slightest idea—not the slightest—what a wok is."

Dear Septimus:

I'm sorry that when you came to my house I wasn't at home.

But I must tell you that circumstances have made it necessary to end our correspondence.

After-effects of a recent lobotomy made me realize that I am not ready for a relationship with a man of your sophistication.

If I had a label, like a bottle of wine, you could read it and see that I am the wrong year for you.

Also, I have just sold my sloop.

Regretfully yours,

SWIFTY

(Someday—When I'm Fourteen...? Thank You)

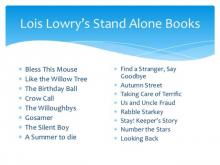

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver