- Home

- Lois Lowry

Find a Stranger Say Goodbye Page 3

Find a Stranger Say Goodbye Read online

Page 3

They shook their heads.

“Neither have I,” said Kay Armstrong. “Nevertheless, it seemed like a marvelous fun thing to do, last night. But I remembered that there aren’t any dandelions in our yard. Natalie’s father is a fantastic gardener. Every spring he does magic things to the lawn, so that there are no broad-leafed weeds. That includes dandelions. Have you ever noticed that we have no broad-leafed weeds in our yard?”

Becky and Gretchen giggled. “No,” they said.

“Well, take a look, when you go out. No broad-leafed weeds. Anyway, as I was lying there half-asleep, I remembered that the neighbors two doors away, the Gibsons, have terrible dandelions. Millions. Obviously they haven’t conquered the broad-leafed weed problem. So I decided to use the Gibsons’ dandelions.

“But the Gibsons are away this weekend. Their daughter is being married in Denver. No way to call and ask their permission.”

She took another sip of coffee. “So I decided to steal their dandelions. I thought I would do it very early in the morning, when no one would see me in their yard.

“So I set my mental alarm clock for five o’clock. Do you girls know how to set a mental alarm clock?”

They shook their heads.

“Well, that’s a different subject, but I’ll tell you about it sometime. It has to do with self-hypnosis. Anyway, five o’clock came, and I woke up, and got out of bed very quietly, because I didn’t want Alden to know what I was doing, in case he would have thought I was quite mad. Do you think I’m quite mad?”

“No,” said Becky.

“Yes,” said Natalie.

“Well, he half woke up anyway, and said, with his eyes closed, ‘What time is it? Where are you going?’ and I said, ‘It’s five o’clock, and I’m going to the bathroom,’ and he said, ‘You should have your kidneys x-rayed,’ and then he turned over and was sound asleep again, and I got my bathrobe and went downstairs.

“I went over to the Gibsons’ yard, through the O’Haras’ back yard, wearing my bathrobe, and when I got there and stood in the middle of all those dandelions … it was a great feeling, incidentally; the sun was just coming up, and the grass was damp, and their yard is bright yellow, it has so many dandelions; it was really exhilarating … I realized I had nothing to put the dandelions in.

“So I took off my bathrobe and put it on the ground and began to fill it with dandelion blossoms. The whole thing was really lovely. I was wearing a white nightgown, and I think I must have looked like a painting by Renoir, bending over and picking flowers in the sunrise. It’s a beautiful nightgown, by the way; would you call it translucent, Natalie?”

“No. Transparent.”

“Perhaps. Well, there was no one around. So I filled up my bathrobe, and pulled the corners together and tied them, so that it was a nice bundle, and then it occurred to me to try balancing it on my head, you know, the way native women do in the South Seas?”

Becky and Gretchen were hysterical.

“Don’t laugh.” Kay Armstrong grinned. “I walked back home, through the O’Haras’ yard, very carefully, with my bathrobe full of dandelion blossoms on my head. It was a nice exercise in posture, I think. Anyway, that’s what I was doing when the milkman drove into our driveway and met me.

“I started to explain to him what I was doing, but I confess that I became a little embarrassed, because I was aware that my nightgown was slightly indecent, although I do think I’d call it translucent, Natalie—

“And of course I couldn’t put my bathrobe on, because it was filled with dandelions—”

“And on your head,” interrupted Gretchen.

“Don’t be silly. Of course I took it off my head when I saw the milkman.

“I could see that he didn’t have the slightest idea what I was talking about, so I thought I would just go into the house pleasantly without any further conversation. And I said, ‘Have a nice day’ to the milkman, and started to open the back door, but I had locked myself out.

“I had to ring the bell quite a while before Alden woke up and came down, and in the meantime the milkman didn’t know whether to go or stay, so he stayed, and when Alden appeared at the door, there I was in my nightgown, holding my bundle of dandelions, and the milkman standing there looking stricken, as if he had walked into a lunatic asylum by mistake.”

“What did Dr. Armstrong say?” asked Becky.

“He just stood there for a minute, and then finally said, ‘Didn’t you have to go to the bathroom?’ The milkman fled.” Kay Armstrong dissolved in laughter.

“Then later,” she said, “I realized that I haven’t any idea how to make dandelion wine. It didn’t even seem a good idea, anymore. So I put all the dandelions in the sink, and two bumblebees flew out and stung me on the arm, which made me feel that the dandelions are decidedly hostile to the whole thing as well, and now—” she got up, went to the sink, and pressed a switch—“I am sending them all down the garbage disposal.”

“‘Sic transit gloria.’” Gretchen laughed.

“What does that mean?” asked Becky.

“It means I’m going to be sick, gloriously, from laughing.”

“Nat,” said Becky seriously, when they were in Natalie’s bedroom later, “how can you not be satisfied with your mother?”

“I am,” said Natalie. “It has nothing to do with that at all.”

7

GRADUATION DAY was like every other Graduation Day. She had attended them for several years, had watched her friends stand there on the stage in their caps and gowns, the girls holding red roses, some of the kids collecting their awards, some of them wearing the special stoles that indicated particular honors. The school band, heavy on clarinets, playing the school song; the tears and smiles; the traditional flipping of tassels from one side to the other. The proud parents with their flashcubes popping. The speeches: they were the same, really, every year.

But because it was her graduation, because it was her father carefully focusing his camera to get what she knew from experience would be blurred snapshots of decapitated people, Natalie listened to the nervous voices of the three students chosen to speak, and tried to attach some meaning in their words to her own life.

Gretchen was one of the speakers. Her high grades had consistently led the class for years, and she had won the scholarships that would take her to Wellesley to study political science. Natalie grinned when Gretchen rose to speak, knowing that under the heavy graduation gown, her friend was wearing patched and faded denim shorts. It was a hot day; summer had really come, and was welcome.

“Commencement,” Gretchen began, “means Beginning.” Some of the students glanced at each other, and smiled. How many graduation speeches had started, “Commencement means Beginning”?

Natalie found her family in the crowd. Her father was solemn and attentive, wearing his best suit, and for once the ends of his stethoscope were not protruding from his breast pocket. Nancy was beside him, her hair curlier than usual from the humidity of the early June afternoon, her blue eyes darting here and there as she searched in the audience for her friends. Nancy wasn’t listening, Natalie knew. It didn’t matter, she thought. Next year, when Nancy graduates, someone will stand up here and say the same thing again: “Commencement means Beginning.” Her mother, her face youthful and attractive, was listening, but she was watching Natalie, not Gretchen. Nat caught her eye and they winked at each other and grinned.

The Branford High School gym looked more austere than it ordinarily did. During basketball season, there was usually a huge, clumsily lettered sign that said “Be an Athletic Supporter” taped to the wall behind the far basket. That was gone. For the senior prom in May, the gym had been transformed by dim light, crepe-paper streamers, a mirrored revolving ball hanging from the center of the ceiling to catch the colored lights, and tables covered with pastel cloths had been arranged around the sides of the room. All those one-night bits of magic were gone, too.

So it was just a gym. Still, it seemed awesome, the w

hole atmosphere of graduation.

“But there are beginnings, perhaps,” Gretchen was saying slowly, “that shouldn’t be made at all.” Natalie watched her and listened more closely.

“We must examine our own motives. Might we be embarking on quests beyond our capacity for understanding?

“We have become complacent here, as seniors. We’ve been the school leaders—the guys who know it all, have done it all. We’re old enough now to be on our own. Some of us will be going to college, some off to full-time jobs, some to be married—” the graduates all grinned at Marcia Pickering, who blushed and polished her tiny diamond ring with one finger—“and to be honest, we, all of us, think we’re pretty hot stuff right now.

“But we’re very young. We shouldn’t forget that. We shouldn’t forget that there are doors not ready to be opened. That if we choose certain paths we may be unhappily surprised by where they lead. And we shouldn’t forget that those who have helped and advised us till now—our parents, teachers, and others—are still here to give help, and advice, and, when we need it, sympathy and understanding.

“Most of you remember the movie Bambi. How Bambi stood at the edge of the forest and was frightened of the big, open meadow, as he had every reason to be. There were dangers there.

“We will all have to go into the dangerous and unknown places that await us. But we should be careful not to rush, not to move ahead without thinking. We should save each beginning until we are prepared to face everything it leads to

“If we do, each Commencement after this one will bring growth and meaning to our lives.

“Thank you.”

Gretchen sat down, embarrassed by the applause, grateful to be finished. Natalie looked over at her, caught her eye, smiled, and gave her a thumbs-up sign.

Then the speeches were ended, the diplomas awarded, the tassels flipped, the school band prodded by the music director into a final march, and the graduates moved in double rows down the aisle and out of the wide door at the entrance to the gym. Natalie found her family in the crowd. She gave her rose to Nancy, hugged her parents, and threw a kiss across the front lawn to Paul, who was standing sheepishly in front of his father’s Instamatic camera, saying “Cheese.”

“Let’s go home!” urged Nancy.

“Oh, wait, I want to see all my friends,” said Natalie.

“Nat, let’s go home. There are presents,” said Nancy.

Natalie laughed. Nancy was still, at sixteen, awake before dawn on Christmas morning; Nancy still said the word “presents” with all the uninhibited glee of a four-year-old—even if the presents weren’t for her, and that was one of the nice things about Nancy.

She opened the gifts in the living room at home, and her mother took the ribbons as she unwrapped the packages, one by one, and arranged them on Natalie’s head. By the third she was festooned with curled-ended bows, yellow, green, and pink, and felt like the Alice in Wonderland illustration of the Dutchess’ baby in its huge ruffled cap. She felt self-indulgent and silly, as if she had been sipping champagne.

From Nancy, there was a fragile silver necklace, a small shining knot caught at the end of a smooth-linked chain. She held it over her hands and remembered how, as a child, she had tried once to capture a small waterfall, in vain. Then she fastened the clasp at the back of her neck and smiled at her sister.

Aunt Helen was on a Mediterranean cruise; she had sent a package. All four of them found themselves glancing inadvertently at the top of the television. The package was too small to be another panther.

“I could save it till last,” Natalie suggested.

“No, get it over with,” said Nancy practically. “Save Mom and Dad’s till last.”

“I wonder if it’s membership in the exotic-fruit-of-the-month club,” said Natalie’s mother, remembering a year when they had dutifully unpacked, month after month, unidentifiable squishy, semi-rotted sweet-smelling things that they had pondered and then sent down the disposal.

“Hey!” said Natalie in pleased surprise, holding it up. “Look!” It was a leather-bound medical dictionary.

Her father exhaled in startled relief. “She’s mellowed,” he said. “At last.”

Kay Armstrong chuckled. “Like the mango?” she said. The mango, indeed, had mellowed. It had mellowed all over the inside of the box in which it had been packed, during its month as exotic fruit, and had dripped, as they carried it, noses averted, to the sink.

“No,” said Natalie. “Aunt Helen’s okay.” She opened the cover of the book and read the inscription that her father’s sister had written. She grimaced. “Well, she’s semi-okay.”

“Semi-Horrible Aunt Helen,” said Nancy. “What did she write?”

“Just one of her pronouncements,” Natalie said. “Are you sure you want to hear it?”

“No,” said her father. “But read it anyway.”

Natalie stood, faced them, and tried to assume Aunt Helen’s pinched-mouth voice. “‘It is not a field for a woman,’ she read, ‘but since you have chose Medicine, you have my wishes for success.’”

They all sighed. “You’re right, Nancy,” said Dr. Armstrong. “She’s my sister, but she’s semi-horrible.”

“Like a semipermeable membrane,” suggested Natalie’s mother. “Some things get through. But not enough. Well, it’s a nice dictionary.”

(“Well,” she had said once, “it’s the nicest green ceramic panther I’ve ever seen. I’ll give it that.”)

“Open Tallie’s,” said Nancy impatiently. “Open Tallie’s.”

They said it every Christmas, every birthday: open Tallie’s, open Tallie’s.

Tallie Chandler was Natalie’s only living grandparent. The sculptor, her mother’s mother, lived in a Boston apartment in the winter, and spent her summers on an island off the coast of Maine. By car and boat, she was only five hours away; but there was nothing, not even a granddaughter’s graduation, that would take her from Ox Island. “She came to our wedding,” Kay Armstrong had explained once, laughing, “but only because we scheduled it for the weekend before she was leaving Boston, and we had it at her apartment.”

The package was heavy. Underneath its outer wrappings, the box was wrapped in off-white tissue paper that had been block-printed with an abstract design in blue and green.

“She’s incredible,” murmured Dr. Armstrong. “Look at that, Kay. She did that paper by hand. She should have signed it. You could frame it, if it weren’t folded and wrinkled.”

Kay Armstrong smiled. “When I was a little girl,” she mused, remembering, “every meal we had—every meal—looked like a still life that should have a frame around it. I remember once, when I was very small, watching her arranging breakfast on four plates. We were in Italy at the time, and there was a guest at the house; I forget who. And I asked her why she was taking so long. I was hungry. She laughed, and said she was just perfecting the symmetry before she served it.”

“Open it,” said Nancy.

Natalie set the paper aside carefully and opened the box. She gasped.

It was a small, gleaming, perfectly cast piece of bronze sculpture. It was abstract, but there was all of nature in it. It could have been a gull at sunrise, motionless, with its head caught, bent, in the fold of a wing; it could have been the thick, unopened leaves of a deep-forest wild plant in early spring. Natalie turned it gently in her hands, and it caught the sun. In the base, Tallie had etched her signature.

A small white card had fallen from the box. Natalie picked it up and read aloud, “Natalie dearest. I have titled this piece ‘Commencement,’ and I created it with my namesake in mind. May it bring you joy. May all Commencements bring you joy. Tallie.”

“You know,” said Dr. Armstrong after a moment, “that’s worth a fortune.”

Natalie held the sculpture and stroked its perfect curved lines with her hand. “It would be worth a fortune,” she said, “even if it weren’t worth a fortune.”

She set it on the coffee table so that the sun, coming

through the west windows of the room, enlarged its shadow into a curved image on the polished pine.

“Now I’ll open yours.” She smiled at her parents.

Their gift was a small box. When Natalie removed the paper, she saw the department store label on the cardboard box, and some familiar Scotch-tape marks on the sides. “Mom,” she said. “This is the same box that held the necktie I gave Dad on Father’s Day!”

“Well,” her mother laughed. “Don’t knock it. Recycling is environmentally sound.”

Inside the box was simply a thin stack of papers tied with a ribbon. On top of the tied packet lay a folded sheet of stationery. She opened it, puzzled, and read the letter that was typed on her father’s office letterhead.

***

Our dearest Natalie,

This gift is from your mother and me, with all our love. And it is from Nancy, who persuaded us that it was what you deserved to have.

We will give you the summer—this summer of your graduation—to make the search you want to make for your own past.

The box contains all the documents we have. They are very few, and your search, I’m afraid, will be a difficult and perhaps a painful one.

Your job at my office begins, as you know, next Monday. I need your help there, and I think you need the experience there to make your choice of a profession a reasoned and meaningful one. But I have scheduled your work this summer to run only through each Thursday at noon. So you will have three and a half days of each weekend to do whatever you must.

I have opened a checking account in your name and placed enough money there to make possible whatever traveling you will find necessary. The checkbook is also in the box.

You will find, also, a set of keys. I have leased a car for your use this summer as well.

You are mature, sensitive, and responsible. We wish you success in whatever journeys you make in these next three months. But we want you to know, also, that what you find is not important to us. You are our daughter, and our friend as well. We love you for being Natalie, and that’s all that matters to us.

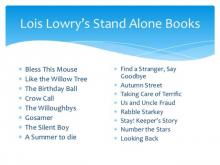

The Willoughbys

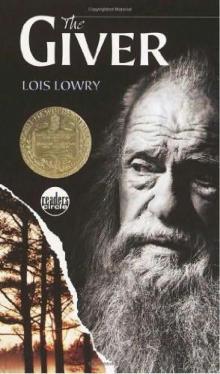

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver