- Home

- Lois Lowry

Find a Stranger Say Goodbye Page 4

Find a Stranger Say Goodbye Read online

Page 4

Both of her parents had signed the letter. Natalie was crying by the time she read their signatures. She folded the paper again, took the bouquet of bright ribbons from her hair, and hugged them.

“Thank you,” she said. “Thank you.”

Then she whispered also, “I’m sorry.”

8

MUCH LATER, in her room alone, Natalie opened the box again. She felt curiously frightened. It was what she had wanted; now, holding the clues to her own past in her hands, she felt uncertain. Paul had said, “Why bother? The present is enough. Today is enough.” And perhaps it was, after all. Tallie’s sculpture sat on her desk like a symbol of an unopened tomorrow—a commencement—surrounded by the simple, unobstructed lines of today. There seemed none of yesterday’s secrets in the bronze.

But she wanted the yesterdays, though she feared them. She felt as she had, years before, on her first day of school, clutching the security of her mother’s firm hand, terrified, puzzled, not knowing if she would like what she found in this new world, not knowing if it would like her. Still, she had finally pushed her mother’s hand away, then, and whispered, “Go on. I’m okay.” As once her father had left her alone in an examining room, with things that had filled her with fear and pain.

She unfolded the first paper. It was, as the letter had been, typed by her father on his office stationery.

To Whom It May Concern:

My adopted daughter, Natalie C. Armstrong (no, thought Natalie. You have always called me “My daughter”) is undertaking to investigate her natural parentage. She is doing this with the permission and understanding of myself and of her mother.

I would appreciate your cooperation in providing her with any helpful information that might be available to you.

Sincerely,

Alden’T. Armstrong, M.D.

The next paper was obviously older. It was marred at its borders by torn places, and the edges were discolored. It was dated July 10, 1960. Two months before I was born, thought Natalie.

The letterhead was oddly familiar. Harvey, MacPherson, and Lyons, Attorneys at Law, Branford, Maine. Hal MacPherson was her father’s lawyer; the MacPhersons were family friends. They lived two blocks away; Natalie had dated their son a couple of times when he was home on college vacations. What had the MacPhersons to do with her birth? It was disquieting, that all these years, perhaps, the MacPhersons had known something of Natalie that she herself had not known. Not fair. Of course, the fact that she had been adopted had never been a secret. But the MacPhersons? She had always called him Uncle Hal, affectionately. And he had known more of her than she had been permitted to know? Why am I angry? Natalie thought. Is this what Dad meant when he said the search would be a painful one? She smoothed the letter with her hands and began to read.

HARVEY, MACPHERSON, AND LYONS,

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

30 Bay Street, Branford, Maine

102 Caldwell Avenue July 10, 1960

Branford, Maine

Dear Alden:

Please forgive me if I am intruding in a personal matter. But Pat, my wife, is a friend of Kay’s, and she has been aware of the difficulties you and Kay have encountered in dealing with the state adoption agency.

Although you and I don’t know each other well, I am certainly familiar with your reputation professionally as well as through the community services that you have contributed to Branford since you have come here. If I can be of service to you in regard to the process of adoption, I would like to offer my availability.

I don’t know how familiar you are with the process of so-called private adoptions. This is a term, as you perhaps know, applied to those adoptions arranged without going through the official procedures of an agency. There are very often disadvantages to private adoptions; notably, the lack of extensive screening and matching procedures that agencies provide.

On the other hand, there are particular advantages in the case of people like Kay and yourself, for whom agency procedures have become long and frustrating. I would be happy to meet with you and your wife to discuss the pros and cons of private adoption if you would like.

But I am writing this letter because it has recently been brought to my attention, through a lawyer in the northern part of the state, to whom I was talking recently about different matters, that a child will be born shortly—I believe this fall—whose family has sought his advice about private adoption placement. I know nothing about how much importance to place on genetics in such a circumstance; you, as a physician, are much more qualified to deal with that question than I. But the lawyer that I mentioned seemed to find that a matter of concern, and mentioned that this particular infant will be born to parents of substantial intelligence and good health.

If you and Kay would like to talk about this further, please feel free to call me at my office. If it is something that does not interest you, I will understand, and hope, as I said, that you will forgive the intrusion.

In the meantime, let me take this opportunity to congratulate you on the presentation that you made the other night at the meeting of the Medical-Legal Committee of the Bar Association. A fine job; Branford is indeed fortunate to have you in our midst.

Very Sincerely,

Harold MacPherson

Natalie sat on the edge of her bed, read the letter again, and saw that her hands were shaking.

A child will be born shortly. That was me. He wrote about it as if he could have as easily been saying, “A new car will be delivered when the next shipment arrives.”

To parents of “substantial intelligence and good health.” She laughed briefly, and with no humor, to herself. Well, that lets out Fish-Factory Brenda, or her equivalent. I’m glad of that, anyway.

Why am I not very glad about the rest of it?

She lay back on her bed, crossed her hands behind her head, and watched the ceiling of her bedroom where the first car headlights of early evening were crossing it occasionally in patterns that formed, moved, disappeared, and formed again.

It’s because it was all so cold. “A child.” My God. If I had been conceived by my parents, they would have been thinking in terms of “our baby.” Not “a child.” But here, the very first time I appear on the scene, it’s in a letter written by a lawyer—maybe by his secretary—as if I were a pending transaction!

Someone, though, thought Natalie, was thinking of me as “my baby.” Great. And hating the idea of me so much that they were already deciding to give me away! She looked at the letter again. “Have sought his advice about private adoption placement.”

In her mind, she formed a picture, like a scene in a movie, of a couple sitting in a lawyer’s office. The woman pregnant. I was born in September; this letter is dated July. She was very visibly pregnant when she went to this lawyer and said … what? “I am seeking your advice about private adoption placement”? Or: “Listen, I don’t want to keep this kid”?

Was there a man with her? The letter says “family.” Maybe there were children already. Maybe I had brothers and sisters. Maybe they went to the lawyer and said, “Hey, we didn’t intend to have another baby, and now here we are, the wife is pregnant, and we just can’t afford another child.”

Abortion was not legal seventeen years ago. Had they considered it, anyway?

Another picture formed, briefly, and she liked this one a little better. The woman was pregnant, weeping, and beautiful. Her husband held her hand in the lawyer’s office, and explained sadly, “My wife has an incurable disease. She has only a year to live. I can’t raise a child alone. So we want you to find a home for our child.”

But that was romantic and foolish, she knew; the letter had said “substantial intelligence and good health.” Natalie closed her eyes and let the flickering scenes of her imagination drift away as if they were lights moving across the ceiling. Nothing replaced them except emptiness; emptiness diffused by disappointment, pain, and an anger that she couldn’t understand. Finally she sat up, turned on the light against the increasing dark

ness, and took the next paper from the box.

PEABODY AND GOODWIN, ATTORNEYS AT LAW

SIMMONS’ MILLS, MAINE

102 Caldwell Avenue July 25, 1960

Branford, Maine

Dear Dr. and Mrs. Armstrong:

Hal MacPherson has written me of your interest in the child which I have been authorized to place for adoption. He speaks very highly of you as potential parents for this child, and I am delighted to be able to let you know that I see no possible barriers at this point to the adoption taking place.

Let me fill you in to the extent that I am able on the details of the case.

The child will be born in September. The family was referred to me by Dr. Clarence Therrian, a general practitioner in Simmons’ Mills, who has been handling the medical aspects of the mother’s pregnancy.

For your protection and for that of the child, Dr. Therrian and I have investigated the background as thoroughly as possible. Naturally, any specific information about the parentage remains confidential. But I am authorized to tell you that there are no familial diseases on the side of either parent. The general health and intelligence of both parents are substantially above average. The mother is of medium height and weight, with dark brown hair and blue eyes. The father is tall and slender, with brown hair and eyes; he is exceptionally well coordinated, with a great deal of athletic skill.

That is all official information. I will add, unofficially, that I know both parents personally, and feel certain that their combined attributes will bring to this child an unusual combination of attractive characteristics. I have no hesitancy about recommending this as an exceptionally good adoptive risk.

Let me tell you briefly what the adoptive procedure involves. At some point in the next month or so, Hal MacPherson will have you fill out the necessary Petition for Adoption form. He will send it along to me. After the birth has taken place, I will have the mother sign the second page, and the petition will then go to a probate judge. Since you have already been investigated and approved by the state agency, there is no reason to suspect that he would not readily grant the petition.

The Bureau of Vital Statistics will issue an amended birth certificate, naming you as parents, and the original birth certificate will be sealed by the court.

I must remind and warn you of two things.

The mother, until she signs the petition after the birth of the child, is free to change her mind about the adoption. I do not believe she will do so. Nevertheless I would be remiss in not alerting you to the fact that it would be her privilege, and that there have been cases in which the natural mother has had such a change of heart after the child has been born.

Secondly, the name of the natural parents will not be made known to you, nor yours to them. Hal MacPherson will not know the names of the parents, and Dr. Therrian will not know your names. I will be the only party who knows the names of both involved parties, and I feel very strongly about not divulging that information.

If you have made your decision, I would appreciate it if you would get together with Hal and sign your part of the Petition for Adoption, so that he can send it along to me. I look forward to notifying you in September when the birth has taken place, and I take this opportunity to wish you great happiness.

Sincerely,

Foster H. Goodwin

The final paper in the small box, resting on top of the car keys and checkbook, was a folded yellow telegram.

PETITION HAS BEEN SIGNED AUTHORIZING ADOPTION OF SIX POUND EIGHT OUNCE HEALTHY BABY GIRL BORN FOUR THIRTY AM SEPTEMBER FOURTEENTH. PLEASE BE AT MY OFFICE 43 MAIN STREET SIMMONS’ MILLS 2 PM SEPTEMBER NINETEENTH AND I WILL GIVE YOU YOUR DAUGHTER. CONGRATULATIONS. FOSTER H. GOODWIN.

Natalie realized she was weeping, and that the anger had gone. Foster H. Goodwin, she thought, knew my real parents, and he liked them. I can tell that, even though he didn’t say it. And even though he talked of “the child” and “the birth,” which set my teeth on edge, he only did it because he had to. And when I was born…(at four thirty am september fourteenth, she thought, grinning through the warm tears on her face)…he was thrilled, and happy for my parents. And he said “your daughter” to Mom and Dad.

This isn’t going to be hard, after all. Even though he said he felt strongly about not divulging the information, he’s a kind man, and I can make him change his mind.

Natalie looked through the bookcase in her room until she found the large United States atlas that, she realized with a smile, Aunt Helen had given her one Christmas when she would much rather have had a new sweater.

The map of Maine was on page 32. She tilted the lampshade so that the full light of the bulb fell on the page, and searched the state for Simmons’ Mills. Finally she found it; the name jumped out at her from a space in the north-central mountainous section of the state, and she held her finger there and looked at it for a long time. The small circle with a dot in the center, there on the edge of the Penobscot River, was keyed to indicate that Simmons’ Mills had a population between 1000 and 2500.

“Oh, I’m just a small-town girl,” she announced aloud, giggling to herself.

She followed with her finger the route she would take from Branford. Main highways as far as Bangor; beyond that, to the north, it would be increasingly smaller, more curving roads, through the mountains, along the river, to the town where she was born. The town where she would find Foster H. Goodwin and, through him, her real parents.

Then her eyes slid to the coast, and she saw Ox Island, a tiny dark blue dot in the lighter blue of Frenchman’s Bay.

First, thought Natalie, looking with joy at the sculpture that was now in shadows in the dark corner of the room where her desk was, I will go to see Tallie. Tallie has a way of putting everything in perspective, and before I set off on that long road that curves to a place called Simmons’ Mills, I’ll let my grandmother smoothe the edges of my questions into manageable shapes.

9

ON THE MAP, coastal Maine had the erratic pattern of cardiograms that Natalie had seen often in her father’s office; it looked as if someone had taken a pen and drawn an irregular line, without looking, from New Hampshire to Canada at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. The line moved, apparently aimlessly, in and out, forming peninsulas and promontories; it opened into harbors and coves where rivers arrived to empty into the sea.

Driving northeast on Route 1, Natalie was less aware of the random patterns of the coast. But she saw the ocean again and again on her right; she saw it curving around the edges of the small towns, the tide moving restlessly against the pilings that formed part of the docks and the fish-packing plants. It appeared in the desolate places that came now and then suddenly, after a bend in the road, where there were nothing but rocks and wind-sheared trees; and occasionally it was there against a short expanse of sand, where children would be playing with buckets and shovels and touching their toes into the icy water with shrieks of delighted pain.

It took her four hours to reach Northeast Harbor, a pleasant and uneventful drive in the small new car. The brilliant blue of the cove around which the little town clustered in a semicircle was spectacular. Northeast Harbor was a picture-postcard town; she could see the groups of tourists strolling the main street, their cameras dangling, their summer-vacation outfits so new the store creases were still visible. At the boat landing, she could pick out the ferries that took tourists to the bay islands on daily cruises. Natalie glanced down at her own faded jeans as she parked the car at the landing, and was devoutly glad that she was not wearing double-knit slacks, rhinestone-rimmed sunglasses, and driving a car with New York plates.

Snob, she thought, laughing at herself.

She lifted her backpack to her shoulders, pulled her hair loose from its webbed straps, and locked the car. Following the instructions Tallie had provided over the phone, she walked along the docks and looked for a small lobster boat named Egret. It was moored ignominiously behind a larger, more luxurious, cabin cruiser and moved up and down slowly as

the water lifted it and let it go again.

Natalie looked down and waved at the man who sat on the boat with his legs up and a pipe in his mouth.

“Sonny?” She felt a little silly, but Tallie had told her someone named Sonny would be on the Egret.

“You the one goin’ to Tallie’s island?” he asked.

She smiled, nodded, and he reached up to help her aboard.

It wasn’t Tallie’s island. Natalie didn’t know who owned the rest of it, but Tallie owned only four acres of Ox Island, which was two miles long and a half mile wide. It was typical of Tallie, though, thought Natalie, that people thought of it as Tallie’s island.

It was typical, too, of a Maine lobsterman that he would have his jacket buttoned up tight against his chin in June, when the tourists were all in shirt-sleeves and alligator-adorned jerseys, and would be freezing and covered with goose bumps on the water. The breeze was very strong even before the Egret was out of the tight harbor, and downright cold as they crossed the open ocean to Ox Island.

“Do you know Tallie?” asked Natalie. “She’s my grandmother.”

Sonny was at the wheel, steering toward the island, watching the bay, not noticing the cold salt spray that struck his face as the boat moved.

“Yep,” he said.

Natalie smiled to herself and didn’t attempt any more conversation. If I were Tallie, she realized, I’d have him talking in long paragraphs, and before the fifteen-minute boat ride was over I’d know his life history.

Oh well, I’m not Tallie. No one is.

Sonny eased the boat gently toward the decaying dock at Ox Island. He muttered to himself, something about how they’d better fix that before the ice bust it up next winter, someone going to get hurt out here. When the boat was fast against the dock, he took Natalie’s hand firmly and helped her up.

“You be here Sunday at two,” he said roughly. “I’ll take you back.”

“Shall I pay you then?” she asked.

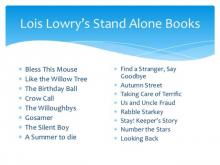

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver