- Home

- Lois Lowry

Find a Stranger Say Goodbye Page 6

Find a Stranger Say Goodbye Read online

Page 6

“Which they won’t answer.”

“Of course they’ll answer. Probably they’ll be really nice people. We’ll have dinner together, or something. They’ll tell me a little bit about what happened seventeen years ago. We’ll talk. I’ll get to find out what they’re like. They’ll see what I’m like. We’ll become friends. It won’t be a big embarrassing deal, or anything.”

“Then you’ll exchange Christmas cards for the next thirty years.”

Natalie laughed. “I told you. We’ll become friends. And we won’t have to wonder anymore whatever became of each other.”

“It hasn’t occurred to you that maybe they’ve never wondered at all?”

“Impossible,” said Natalie firmly.

“Bullshit,” said Paul. “I hope you’re right, Natalie, for your sake. But I think you’re the ‘Best All-Around Crazy Person.’”

He gave the swing a strong push, and they moved suddenly back and forth, the way they had as children, trying to scare themselves into thinking they might fall. She held tightly to his hand.

14

LATER THAT EVENING, after Paul had gone, Natalie opened the small box that Tallie had given her.

If I were Nancy, she thought, peeling away the Scotch tape at the edges, I would have opened this up as soon as I got off the boat from Ox Island. Nancy is the one who leaps in the ocean all at once. And I’m the one who goes in inch by excruciating inch.

For me, she thought, the waiting and the wondering are sometimes the best part of things. Maybe that’s why I’ve kind of cooled it with Paul, when some of my friends have become so heavily involved. I like having things to look forward to.

She removed the lid from the box, and saw the letters that were written in her own mother’s handwriting. She smiled. The small, vertical strokes of Kay Armstrong’s script hadn’t changed, though these letters had been saved for years. There were only a few; Tallie had sorted them, she had told Natalie, and given her just the ones that would add the necessary dimension. Natalie envisioned her grandmother looking through the stack, reading through each letter quickly, with her head cocked sideways like a bird, and making the selection, in the same way that Natalie had watched her paint with bold, carefully considered definitive strokes.

The first letter was dated March, 1960.

Dearest Tallie;

Aren’t you ever going to cut loose from Boston just for a weekend and come to see us in Maine? The house is so spacious, and we have reserved a room for you; I painted it white, and there are plants hanging in the windows and a wonderful patchwork quilt on the bed, in all the shades of blue and green that are your favorites.

Alden is well, and busy. There is such a need for him here.

And I have made friends. There is lots to do, for a small town, even for someone like me who won’t join a bridge group or go to cocktail parties. There are good people in Branford.

Alden had me see a gynecologist in Portland, and the news was disappointing, I’m afraid. The same old tests that I had in Boston, and the same old results. The same “It is very unlikely, Mrs. Armstrong—” etc. The same “Have you considered adoption, Mrs. Armstrong?”

We have registered with an adoption agency, but they are just as dreary to listen to as the doctors. My lord, Tallie, the paper-pushing that goes on! They seem to forget sometimes that they’re dealing with humans. And with babies. They call them “our placements.” “‘Our placements’ have a very high percentage of success.” Ho hum. I don’t care about their placements and percentages; I just want a baby, for pete’s sake. Alden is much more patient and understanding of all the bureaucratic nonsense, and he makes a good impression on them, I’m sure, but then they look at me and stroke their chins and I suspect that they are thinking “Hmmmm … would one of our placements work with this crazy woman who wears jeans to an interview?”

And of course they cringed … tastefully, of course … when they asked about my family background. Turns out my education was what they call “unconventional.” Can’t imagine why! I thought having tutors come and go in Greece, France, Mexico, and Spain was great! Especially when they went, and left the three of us together and we all used to agonize over those schoolbooks and sometimes give up altogether. Remember when Stefan held a ceremonial Book-Burning of Algebra I when none of us could understand the fifth chapter?

Oh well. I wouldn’t trade that for anything, but it is, apparently, making a “placement” difficult. In the meantime, I have left a small bedroom completely empty, waiting. I haven’t given up hope, not at all.

But I would so like a child. A daughter, I confess. I daydream about holding her and singing some of those songs that you used to sing to me when I was small. Off-key, I might add.

Do come to visit. We could drink tea and sit by the fireplace and talk.

Much love,

Kay

June 10, 1960

Dearest Tallie,

Isn’t it wonderful that we are living here, right on the way to Ox Island, so that there was no way you could not visit en route?

I loved having you here; so did Alden. It will take me a week to catch up on the lost sleep, but I have needed someone … especially you … to sit up with and talk to.

No, there is no new news from my visit to the agency. We have been officially approved, whatever that means … I suspect, from the way the woman looks at me, that they have stamped HIGHLY SUSPECT on our papers, but they do say that we passed all the necessary procedures, inspections, whatever.

But that seems to mean nothing, because then they tell us about the WAITING LIST, in hushed voices. Seems there is a LONG WAITING LIST.

Maybe I will just turn the empty bedroom into something useful, like a sewing room, or a place to keep plants, and try to forget that I wanted to hang bright pictures on the walls, and look in at night to see a baby sleeping there.

Oh, dammit, Tallie. You know, I try to be cheerful about it, but I want a baby so badly. Remember, when I was married, I said we would have one right away, and then another every year until there was a houseful? And now we have a houseful of emptiness, and I am so sad. Alden is so good, and says “Wait, wait,” very patiently, but how can you wait forever for something you want so much?

I’m sorry to whine. But you will understand.

Much love,

Kay

July 12, 1960

Dearest Tallie,

I don’t know where to begin this letter. I have been sitting here in the kitchen drinking tea and smiling, all by myself. Pour yourself a cup of tea while you read this and then smile with me.

Alden has been told by a lawyer whom we know slightly that there is a possibility of our adopting a baby privately. Not just “a baby,” but a real one that is already in the making, that already exists! It is to be born in the fall.

I haven’t been able to sleep since we heard. Alden is as always much more circumspect. He is carefully considering all the pros and cons, as he puts it … but I am quite, quite sure that we have already made the decision. He wants it as much as I do, and from what he was told, it won’t be a surreptitious thing. All quite legal; just that we don’t have to go through the long waiting period that the agency has been promising us.

Do you remember what it felt like to be waiting for your child to be born? This is no different from what it would be if I were pregnant. I am so excited … so scared. I worry about whether the baby will be born safely, and be healthy. I lie awake at night and think of all the things that I have waited so long for … to hold my own child, to teach it things, even to knit little sweaters, even though you know how undomestic I am!

I say “it” because I dont want to tempt fate, I suppose, but I feel very certain that it will be a little girl. Alden as usual pretends not to allow himself to be caught up by whims and emotions; he quotes statistics to point out that it is just as likely, more so actually, that it will be a boy. Then, last night, while we were having dinner, he suddenly smiled and said, “Let’s name her for Tallie.”

Will you like being a grandmother? Oh, how I wish Stefan were alive to share this with us all!

Much love,

Kay

August 29, 1960

Dearest Tallie,

Thank you, thank you for the wonderful surprise. When the package came, I couldn’t imagine what it was … knowing that there are no stores on the island … and knowing that you wouldn’t leave the island to go shopping, not even for an impending grandchild!

And there was my own childhood, packed so neatly into the box! That book of fairy tales in French; I remember your reading it to me … where did we live then? I was so small; I can remember the fireplace, and that there were blue bowls on a table, and that you had gold earrings that I used to reach for when you held me on your lap, but I can’t remember where it was.

And those funny pictures that Stefan used to draw for me. I had no idea you had kept them! I am having them framed to hang in the baby’s room. Some of them are quite indecent by Branford, Maine, standards … a nude Red Riding Hood … imagine! I remember laughing and laughing at that. Good thing the agency lady is no longer stopping by to check out our standards!

What fun it will be to share all of those things with my own child. Oh, Tallie, it is so hard to wait. I am knitting the most terrible sweater; the sleeves are different lengths even though I have ripped one of them out twice and re-done it. But it gives me something to do while the time goes by.

Much love,

Kay

NATALIE CHANDLER ARMSTRONG BORN YESTERDAY HEALTHY AND STRONG STOP ALDEN AND I WILL BRING HER HOME IN FOUR DAYS STOP WE ARE SO HAPPY TALLIE STOP KAY

September 20, 1960

Dearest Tallie,

There is so much to say that I don’t know where to begin, and I think I shall save most of it for when you come. When you close the house at Ox Island the end of the month, do plan to spend several days here on your way to Boston, won’t you?

She is so beautiful that when I saw her, I wept.

Her hair is very dark, her features small, and her eyelashes quite long. Right now … she is sleeping here in the kitchen beside me … she looks exactly like the sleeping princess in the picture on page 16 of the fairy tale book you gave me; do you remember that picture, where the princess is waiting for the prince to arrive and wake her with a kiss? There was a time when I scoffed at that and thought it terribly over-romantic. But now I look at this beautiful child, sleeping, and realize that a whole world can lie before someone, if love is there when one wakes.

She is not at all like either of us, Alden or me, and I am glad. She will be her own person. It will be such a joy to watch her becoming that.

Much love,

Kay

Natalie laid the letters aside and closed her eyes. She remembered the book of fairy tales, which her mother had read to her in French, so that the language was strange and musical, and the sense of the tales was there only in the pictures, enhanced by that mysterious sound of words she didn’t understand. Somewhere, she supposed, the book was packed away again, and would be there for her and Nancy to have for their own children.

The drawings that Stefan, her grandfather, had made with pen and ink were still there on the wall of her room. What an irrepressible man Stefan must have been! He had sat, her mother had told her, evenings at their kitchen table and illustrated for her, with his pen, as he told her the familiar stories that all children hear. His marvelous, meticulous drawings made them seem newly invented. There was Red Riding Hood, the one her mother’s letter had mentioned, walking through woods thick with trees almost tropical in their growth, laden with strange flowers, and lurking with snakes and strange beasts almost hidden in the intricate foliage created by his pen. Red Riding Hood was naked, innocent in a child’s nakedness, and her cloak flowed around her as she walked barefoot on the patch of the forest and looked upward with wide and trusting eyes to the heavy growth that surrounded her. There was humor and warmth to the drawing; but the fear was there, too.

It is another dimension, Natalie realized, as she got ready for bed. I always knew how much my parents had wanted me; it was one of the things they told me so often, when I was little, as a way of explaining my adoption. It makes it different, though, reading the letters, and knowing for the first time my mother as a young girl, really.

It explains their hurt, in a way. It doesn’t change things. But it makes me understand everything more. “She will be her own person,” the last letter said, and—she looked at it again—“It will be such a joy to watch her becoming that.”

Well, I will make the trip to Simmons’ Mills, and it will be done. The whole summer will be left, so that their joy will still be there and they will have time to get over the small hurt.

She looked at Stefan’s drawing again before she turned out the light. It was filled with hidden things. The wolf himself was in a corner of the picture, so carefully drawn that he was himself part of the forest. She always had to search for him, when she was a child; and then, when she had found him, felt sad that she couldn’t whisper into the picture and warn the naked child who walked barefoot with her eyes so full of innocent pleasure.

15

THE ROAD to Simmons’ Mills, beyond Bangor, as she had guessed from the map, was narrow, winding, and increasingly deserted. By five o’clock on Thursday Natalie was deep in the rugged, mountainous, awesome terrain of central Maine. The few drivers who passed her coming in the opposite direction were almost all huge lumber company trucks, heavy and noisy on the small road, their flatbeds piled with chained loads of massive logs from the woods.

She had filled the car’s gas tank in Bangor, and was grateful that she had had the sense to do it, because there were no gas stations on this deserted road. No farmhouses. No tourist gift shops such as the ones along the coast, selling their plastic lobsters and varnished seashells. No restaurants. Twice she passed, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, general stores that advertised, in signs glued to their unpainted wooden walls, hunting and fishing licenses as well as Pepsi, beer, and pizza. She didn’t stop, anxious to reach Simmons’ Mills and find a place to stay before dark; the seedy stores disappeared into her rearview mirror and the woods closed around the road again.

To the west, she could see the sun hanging lower in the sky over the mountains: an incredible view from the top of each hill, as the road lifted itself now and then above the level of thick forest and held her there for a moment at a brief crest. She could see lakes, brilliant as broken glass in the reflected light of the low sun, to her left in the distance; and again and again she saw the river with its Indian name, Penobscot, surging heavily in its endless trip south to meet the ocean. Sometimes, she knew, the logs were sent south on the river in great log drives; she noticed, along its banks, occasional logs caught and wedged by rocks, held firmly there, perhaps forever, and causing the swift water to part and move around them in foamy interrupted patterns.

The woods, she knew, were filled with wild creatures: deer, moose, and bear, and the smaller animals that rustled the undergrowth and moved in and out of their deeply hidden burrows in search of food. She had never been, before, to the great central uninhabited part of Maine. It seemed a trip into a primeval time.

When from the top of a hill, suddenly, she could look down and see the town of Simmons’ Mills spread like a small blemish beside the gray river and the vast deep green of woods, she pulled the car to the side of the road and stopped.

The forest parted only slightly for the town, as the river had reluctantly parted to surge around the caught logs. A huge paper mill stood by the river, its tall stacks spewing smoke that hung above them in flattened clouds and then dispersed, its gray tinged pink by the sun that was setting now. Natalie glanced at her watch uneasily; it was almost seven. She had, she realized, made this journey without sufficient preparation for the simple practicalities. She had expected a town to have motels. She had never been in a town without motels; now, looking down at Simmons’ Mills as she eased the car back onto the road and started down the hill, she realized that Simmons’ Mills was not a place that tourists would come to. From the hill, she could see that the outskirts, the place where one ordinarily found motels and restaurants, consisted only of a few farmhouses on land carved from the woods, placed at random like ornaments dangling from a string—the road—that fell in curves as if it had been dropped in haste.

She passed the farms, poor ones, with boulders in their pastures, and barn roofs sagging from the great weight of snow in winter, and drove into Simmons’ Mills. One main street. She smiled, remembering that she had wondered briefly why Foster H. Goodwin’s letter to her parents had had no street address. Now she realized that it wouldn’t be necessary in a town the size of Simmons’ Mills. But the telegram had directed her parents to 43 Main Street; she was passing that now: a brick building, two stories, with a drugstore on the ground floor. Offices upstairs, she supposed. That’s where I will find Foster Goodwin. That’s where, she realized suddenly, my parents came to get me. What a strange feeling it must have been, for them, to come to the top of that hill, to look down at this town, and to think “Our daughter is there.”

Finally she breathed deeply and smiled in relief. Around the corner from Main Street, beside a church, she saw a white frame house with a sign in front of it: guests.

Well, thought Natalie, I will be a guest in my own home town. She pulled her car into the driveway, and went to the front door.

The woman who answered her ring was pleasant, with a pink, lined face, bifocal glasses, and some knitting in one hand. From another room, Natalie could hear a television set; a familiar voice was giving the evening news in solemn tones. So Simmons’ Mills isn’t the end of the earth after all; they still listen to the news of wars and crime and disasters, Natalie thought. I bet they haven’t had a crime here in years. Who would bother?

“Are you all alone, dear?” The woman glanced over Natalie’s shoulder, toward her car.

“Yes. I need a place to stay tonight. Maybe tomorrow night, too.”

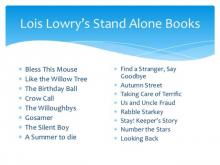

The Willoughbys

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver