- Home

- Lois Lowry

Find a Stranger Say Goodbye Page 5

Find a Stranger Say Goodbye Read online

Page 5

“She took care of it.” He turned to his engine, ignoring her thank you.

Tallie wasn’t at the dock. Natalie hadn’t expected her to be. Tallie had never, according to Natalie’s mother, been on time to anything in her life.

But she was at the house. Natalie walked up the dirt road, opened the never-locked door, and found her there, busy in the kitchen, singing “Un bel dì vedremo” from Madama Butterfly, loudly and slightly off-key, as she stirred something on the stove.

She looked up in surprise. “Natalie! Is it four o’clock already? I meant to be at the dock to greet you! But one of the local fishermen stopped by this morning with the most wonderful gift of lobsters and scallops and halibut that I decided to make a paella … have you ever tasted paella, Natalie? Look, how the saffron changes ordinary rice to such a marvelous shade of gold!…and my goodness, I’ve lost track of the time. You look absolutely beautiful. I have always thought of you as a Modigliani person, and look … you’ve proven me correct by wearing your hair that way, so that it falls into those elongated lines. Are you hungry? Warm enough? In need of music? Let me put on some Bach, so that everything will seem orderly and precise.”

Natalie shrugged off her backpack, laughing, because Tallie never changed; she was still the same; no matter what happened, Tallie would always be indescribable. She ran to her and hugged her, and they held each other for a long time.

10

THEY HAD TALKED and talked.

“Natalie,” Tallie said at last, “even though you’re certain that you want to—that you have to—make this search, you’re frightened. Don’t be. You can handle whatever you find. And of course one must find out everything. It’s exactly what I would do myself. I’ve spent my life finding out everything I possibly can.”

They were sitting, after supper, in the living room of Tallie’s tiny, eighteenth-century farmhouse. It was, Natalie thought, her favorite room in the whole world. The past was in it, in the ancient pine boards of the floor, and in the small-paned windows with their interior shutters that had once been used to keep out unfriendly Indians, or, more often, the bitter winter wind. But the past was layered over by the present, and by Tallie’s presence, in the form of the brilliant white paint with which she had painted the plaster walls, and over which she had hung vivid and abstract paintings. The hanging plants. The shaggy Danish rug in earth shades of brown and gray on the floor. The thick pottery ashtrays and bowls on the low tables. The bright woven pillows strewn at random on the low white couch. Everywhere, the books. And the music. Tallie’s life was always filled with music. She had put a recording of noisy, quick Russian dances on her stereo; there were clapping and stamping combined with the abrupt and discordant melodies. Tallie had served tea on a tray: a murky tea to which she had added herbs that she had collected on the island and dried herself. She poured it from a rounded earthen pot into deep gold glazed-clay mugs. Natalie blew ripples into the surface of hers, and tested it with the tip of her tongue.

“But you know, Tallie,” she said slowly, “Mom and Dad say they understand why I’m doing it, but they don’t really. They’re very hurt. And I’m not sure I understand myself, why I’m doing it.”

“You have incredibly lovely feet, Natalie. You should always go barefoot. Of course they’re hurt. Sometimes we have to hurt people, in order to keep ourselves whole. We must just do it with love, that’s all.”

“That doesn’t make much sense to me,” admitted Natalie.

“Where is it written that anything has to make sense? All I mean is that when you have to hurt someone you love, do it honestly. And you’re doing that. You could have sneaked around and done what you’re doing. It would have been more difficult, of course, but you could have done it, Natalie. And you didn’t. You told them exactly what you were doing. And it hurt, but they know you love them.”

“I bet you never hurt anyone, Tallie.”

Tallie hooted with laughter, and reached for the pot to pour more tea. Her rings glittered in the soft light, and made small noises as the silver touched the thick pottery. “How do you think I learned? Of course I’ve hurt people. I ran away from my first husband in order to go off with your grandfather. You look shocked, Natalie. Didn’t your mother ever tell you that?”

Natalie shook her head.

“Well, it’s true. I lived in sin for quite a while before my first husband finally divorced me on grounds of adultery.

“Actually—” Tallie sipped her tea. “I lived in Italy.” She chuckled. “Technically, it was in sin, at least according to my family and to the New York newspapers. But geographically, it was in Italy. That seemed the more important thing, since I couldn’t speak a word of the language at first. Goodness; I wonder if there is a language for people who live in sin.”

The music had ended, and the old farmhouse was very quiet. A pale moth fluttered close to the small flame of the candle; the woman and the girl watched with vague amusement as the translucent wings drew it again and again to the potential danger. Finally Tallie caught the moth lightly with her quick hand, opened the window behind her, and released it to the night.

“They’re so terribly fragile,” she said. “I hope I didn’t damage the wings. One tries so hard to save something, and sometimes things are injured in the saving.”

She sighed. “It’s the same thing we were talking about. I hurt people, by trying to save myself. Perhaps that was a brutal example. But there I was, twenty years old, madly in love with the most exciting man I’d ever met … have still ever met … and I was married to someone else. So what was I to do? Stay in New York the rest of my life, as the wife of a stockbroker who tucked his pajama tops carefully into the bottoms and wound his watch four times exactly every night before he went to bed?”

Natalie giggled.

“Or run off to Florence with an incredibly fine painter? Did I ever tell you how I met Stefan, Natalie? That he came over to my table in a New York restaurant and said, ‘I want to paint you’? It sounds so trite, now; but nothing about Stefan was trite. Oh, Natalie, it was so exciting. And so painful.

“But there simply isn’t any choice when you know you have to do something. So you inflict the hurt, and you smoothe it as much as you can by saying ‘This is my fault, not yours—’ Your face is brightening. You said that, did you?”

Natalie nodded. “More or less.”

“And it works out. You get through the pain, and it works out. In my case, I found incredible happiness. And my first husband married again, to a woman who was perfectly suited to him, who gave elegant dinner parties using the china he had inherited from his mother.” She grimaced. “It was hideous, Natalie. Big green birds of paradise in the center of each plate; can you imagine? And they lived happily ever after. His obituary in the New York Times was twelve inches long, which surely would have pleased him; and it never mentioned that once, long ago, he had announced that he was going to jump out of his office window if I left. He did, Natalie, he said that as I was packing my bags, and all I could think of, even though I knew he would never really do it, was that he had always abhorred anything messy.”

Natalie sipped more of her tea and smiled. “Well, Mom and Dad aren’t that upset.”

“Of course not. Your parents are sensible people. I’m being silly, dredging up my own insane past as an example. They’ll get through it, and so will you, and you’ll find your own past. If you like what you find, embrace it. If you don’t, shrug it away.”

Natalie curled into the corner of the wide couch, against the pile of bright cushions.

“Your mother used to do that when she was a little girl. Curl up into corners. I suppose it was because Stefan and I were forever taking her to places where we stayed longer than we thought we would. Sometimes days longer. Poor Katherine, we would find her curled in corners, fast asleep. Sometimes I think I was a bad mother.” Tallie fitted a long cigarette into an even longer holder, and leaned forward to light it in the flame of the candle that still burned in its squat sculpted container on the table.

“Oh, you weren’t, Tallie. I’m sure of it. Mom tells wonderful stories of her childhood.”

Tallie smiled. “It’s good having you here, Natalie. My Modigliani granddaughter. Do you think I look old?”

Her face was lined, and her hair was gray, but her eyes were dark and vivid, her mouth and hands alive and expressive. She was slender and small. “No,” said Natalie honestly. “You don’t even look old enough to be a grandmother, to me.”

“Damn.” Tallie laughed. “Thank you, I guess. But I am dying to be a fascinating old woman. Next year, perhaps.”

She picked up the empty tea things and took them to the kitchen. “Let’s go to bed now, Natalie,” she called, “so that we can get up early tomorrow and have an all-day picnic. I’ll take you to my favorite cove. How do you feel about going skinny-dipping in ice-cold water with an elderly friend?”

“I’ll try anything once.” Natalie laughed as she carried her backpack up the stairs.

11

“I WISH I didn’t have to go back,” said Natalie sadly as she walked with Tallie to the boat landing on Sunday afternoon.

“Stay, then. We’ll pick wild strawberries and make jam.”

Natalie sighed. “I have to work tomorrow. Dad needs me. And the next free weekend I have—”

“You’re going to go to that place—what was the funny name it had?”

“Simmons’ Mills.”

“Simmons’ Mills. Yes. You’ll find things there that will surprise you, Natalie. You’re not afraid of them, are you?”

Natalie laughed uncertainly but she said, “No. I think they’ll probably be very ordinary things. Nothing to be afraid of.”

Sonny, still buttoned up in his salt-stiffened jacket, helped

her into the rugged little boat. She reached up and held Tallie’s hand tightly for a moment; then Sonny revved the engine and the boat moved gently from the dock.

Tallie had wrapped her arms around herself to shield her body from the chilly wind that was lifting foam from the murky and turbulent water of the bay. Natalie watched her grandmother diminish in size as the Egret carried them steadily apart, until Tallie was no more than a speck on the outlined edge of the island dock, and then she was nothing at all as light gray fog appeared and blurred the transition between sky, land, and sea.

Natalie felt the edges of her backpack to assure herself that the small box Tallie had given her was still safely there. “Open it later,” Tallie had said, “when you have time, and solitude. I don’t know if it will help at all. But it will add another dimension. In art, it’s important to find all the dimensions, even if you choose to discard some.”

12

“MOM,” said Natalie the following Tuesday evening, when she had come home exhausted from work and was resting in the kitchen with her shoes off, “why didn’t you ever tell me that Tallie had been married before?”

Her mother was stirring spaghetti sauce. She put the lid back on the heavy cast-iron pot, and turned to Natalie with a puzzled, surprised look.

“Nat, you’re not going to believe this. In fact, if I were you, I know I wouldn’t believe it. But I forgot.”

“You’re right. I don’t believe it.”

“No, really. Of course, Stefan Chandler was my father. An incredible man. I so wish that you girls could have known him. And Tallie—my mother—did tell me that she’d been married before. I don’t think she ever told me any of the details. It wasn’t important. Tallie and Stefan were such a … well, how can I describe it?…theirs was such a good marriage. It was as if they must always have been together. They adored each other. They adored me, too, when I came along, and they made me part of it, of whatever they had.”

“And you really didn’t remember about her first husband?”

“No. Not until you mentioned it. But now I remember that she showed me a clipping once, his obituary—”

“It was twelve inches long, she said.”

“Leave it to Tallie to make an obituary sound mildly obscene!” Kay Armstrong sat down at the kitchen table and smiled. “What else did she tell you?”

Natalie grinned. “That she was a terrible mother, and you used to curl up in the corners of strange places and sleep because she forgot to put you to bed.”

Her mother laughed affectionately. “Yes, I remember. She and Stefan used to take me everywhere. There were always loads of people—isn’t it funny, how she’s preferred solitude, since he’s been dead?—and they would talk, and sing, and dance, and argue. After a while I would find myself a comfortable little spot somewhere and curl up, just the way she said.

“She’s teasing, though, when she says she was a terrible mother. She was the best kind of mother. Did she tell you, though, that it hurt her dreadfully when I decided to marry?”

“It did? No, she didn’t tell me that. Didn’t she like Dad?”

“She does now. But then—well, I guess it was because he was so unlike Stefan. And Stefan had died only the year before. I think she hoped I would perpetuate that kind of wonderful crazy happiness by marrying someone exactly like him, so there would be three of us again.”

“Was it hard for you, to disappoint her?”

Her mother thought. “No, strangely, it wasn’t. Because I was all grown up then, and I knew what she wanted wasn’t the same as what / wanted. I told her that. We were always very honest with each other. She understood. After a while, it was all right. She didn’t tell you any of that?”

“Actually,” said Natalie, “I guess she did. It was part of what she was saying.”

13

TALLIE HAD SAID to wait until she had time, and solitude. They were both hard to come by. Her job took long hours of the day, frequently running over through dinnertime if there were patients still in the office; when she went home in the evenings, she went home still saturated with the burdens of other people’s pain and with the stimulation of watching her father go about the intellectual and intuitive process of healing.

Most evenings, she saw Paul. He was working at a construction job, earning money that would help him through Yale. At night he would stop by, exhausted, and they sat on her porch, sipped iced tea, and talked. Sometimes she felt, sadly, that they had already entered two different worlds. His was the world of sunburn and sweat, and of men. When she asked him what he had done that day, he told her of the men he worked with—people she didn’t know. Their talk, on the job, was of TV shows and women, Paul said, amused. They had asked him to join a bowling team and to drive with them to Boston some weekend for a Red Sox game.

High school seemed in the distant past, through it was only three weeks before that they had stood in the gym at graduation and whispered familiar jokes to their classmates, about teachers and shared pranks. Paul felt it too, the quickness of the transition. Two of their classmates had already joined the Navy; one other was married. The local newspaper had carried a picture of her on Sunday, wearing a white veil and smiling shyly over a bouquet of carnations. Four weeks before the same girl had been called into the principal’s office for a lecture when she had been caught smoking in the girls’ bathroom. Now she would be settling down in an apartment full of furniture sold in matched sets at Sears, joining the other housewives in their morning trips to the supermarket, carefully sorting the coupons from last night’s paper, and waiting idly at the Laundromat while the week’s wash floated like a collage in the dryer.

Another boy, someone they knew only slightly, had been killed two days after graduation, when he drove his car into a tree at midnight after a party. The Class of ‘77, which had stood in a proud group arranged according to height and wearing rented maroon graduation gowns, was already history. “What happened to———” people would ask before long, and the answers would come, in many cases, as surprises. The Class Clown would be working in his father’s company, selling radial tires. The Class Flirts, photographed for the yearbook in a silly, amorous pose, had gone separate ways, the girl to beauticians’ school in Portland, and the boy studying aeronautics in New Hampshire. The Class Intellectual, Gretchen, was working in a summer camp in Vermont; Natalie had had a brief letter from her, filled with funny remarks about the crafts—basket-making and what Gretchen called “wavery weaving”—that she taught to rich people’s children, and the news that Solzhenitsyn, in exile from Russia, was living only twelve miles away. On her day off she had passed the long fence that surrounded his house, and wanted, she wrote whimsically, to call over it “I love you.”

“Here we are,” said Natalie, laughing to Paul, “the ‘Best All-Around Girl’ and the ‘Most Likely to Succeed Boy,’ and we’re too lazy to do anything except push this swing back and forth with our feet.”

“And hold hands,” added Paul, squeezing her hand. “Nobody ever said I was most likely to succeed immediately. And you’re definitely the best all-around hand-holder I know.”

“Oh, well. We’ll set the world on fire someday. Right now it’s nice to be lazy.”

“You want to go to the movies Friday night?”

Natalie shook her head. “I’m leaving Thursday, and going to Simmons’ Mills.”

Paul sighed. “I really think you’re crazy, Nat. You’re going to go up there and talk to that lawyer—what was his name?”

“Foster H. Goodwin.”

“You’re going to go talk Foster H. Goodwin into telling you who your parents are, and then what? You’re going to go knock on their door. I can see it now. They’ll be living very peacefully in a split-level house, with five kids and a dachshund and a couple of Snowmobiles. Up comes Natalie Armstrong, up the front walk. Knock knock knock. ‘Hello,’ you’ll say. ‘Remember me?’ What happens then?”

Natalie made a face at him. “Paul, give me credit for a little good sense. I don’t know exactly what I’ll do, but I’m certainly not going to march up to their front door. Maybe I’ll write them a letter.”

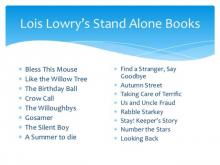

The Willoughbys

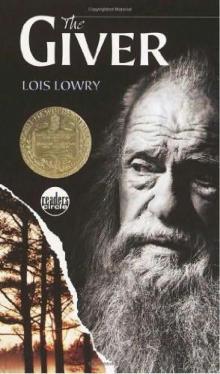

The Willoughbys The Giver

The Giver Messenger

Messenger Gathering Blue

Gathering Blue Gooney Bird and All Her Charms

Gooney Bird and All Her Charms Taking Care of Terrific

Taking Care of Terrific Gooney Bird on the Map

Gooney Bird on the Map The Birthday Ball

The Birthday Ball Anastasia's Chosen Career

Anastasia's Chosen Career Number the Stars

Number the Stars The Silent Boy

The Silent Boy Son

Son Attaboy, Sam!

Attaboy, Sam! Gooney Bird Greene

Gooney Bird Greene The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline

The One Hundredth Thing About Caroline Anastasia Has the Answers

Anastasia Has the Answers Your Move, J. P.!

Your Move, J. P.! See You Around, Sam!

See You Around, Sam! All About Sam

All About Sam Rabble Starkey

Rabble Starkey A Summer to Die

A Summer to Die Anastasia at This Address

Anastasia at This Address Anastasia Again!

Anastasia Again! Gooney the Fabulous

Gooney the Fabulous Gossamer

Gossamer Anastasia, Absolutely

Anastasia, Absolutely Gooney Bird Is So Absurd

Gooney Bird Is So Absurd Anastasia at Your Service

Anastasia at Your Service Bless this Mouse

Bless this Mouse Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye

Find a Stranger, Say Goodbye Autumn Street

Autumn Street Stay Keepers Story

Stay Keepers Story Anastasia Krupnik

Anastasia Krupnik Zooman Sam

Zooman Sam On the Horizon

On the Horizon Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst Us and Uncle Fraud

Us and Uncle Fraud Switcharound

Switcharound The Willoughbys Return

The Willoughbys Return Dear America: Like the Willow Tree

Dear America: Like the Willow Tree Shining On

Shining On Messenger (The Giver Trilogy)

Messenger (The Giver Trilogy) Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver

Giver Trilogy 01 - The Giver